Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of proteins

The field was pioneered by Richard R. Ernst and Kurt Wüthrich at the ETH,[1] and by Ad Bax, Marius Clore, Angela Gronenborn at the NIH,[2] and Gerhard Wagner at Harvard University, among others.

Structure determination by NMR spectroscopy usually consists of several phases, each using a separate set of highly specialized techniques.

These properties depend on the local molecular environment, and their measurement provides a map of how the atoms are linked chemically, how close they are in space, and how rapidly they move with respect to each other.

Frequently, the interacting pair of proteins may have been identified by studies of human genetics, indicating the interaction can be disrupted by unfavorable mutations, or they may play a key role in the normal biology of a "model" organism like the fruit fly, yeast, the worm C. elegans, or mice.

The source of the protein can be either natural or produced in a production system using recombinant DNA techniques through genetic engineering.

Recombinantly expressed proteins are usually easier to produce in sufficient quantity, and this method makes isotopic labeling possible.

[citation needed] The purified protein is usually dissolved in a buffer solution and adjusted to the desired solvent conditions.

However, in large molecules such as proteins the number of resonances can typically be several thousand and a one-dimensional spectrum inevitably has incidental overlaps.

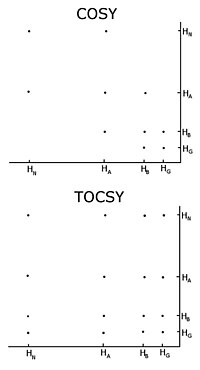

The additional dimensions decrease the chance of overlap and have a larger information content, since they correlate signals from nuclei within a specific part of the molecule.

Thus, in the 15N-HSQC, with a 15N labelled protein, one signal is expected for each nitrogen atom in the back bone, with the exception of proline, which has no amide-hydrogen due to the cyclic nature of its backbone.

Analysis of the 15N-HSQC allows researchers to evaluate whether the expected number of peaks is present and thus to identify possible problems due to multiple conformations or sample heterogeneity.

The neighbouring residues are inherently close in space, so the assignments can be made by the peaks in the NOESY with other spin systems.

[citation needed] One important problem using homonuclear nuclear magnetic resonance is overlap between peaks.

The HNCO contains the carbonyl carbon chemical shift from only the preceding residue, but is much more sensitive than HN(CA)CO.

In the NOESY-based methods, additional peaks corresponding to atoms that are close in space but that do not belong to sequential residues will appear, confusing the assignment process.

Direct access to the raw NOESY data without the cumbersome need of iteratively refined peak lists is so far only granted by the PASD[10] algorithm implemented in XPLOR-NIH,[11] the ATNOS/CANDID approach implemented in the UNIO software package,[13] and the PONDEROSA-C/S and thus indeed guarantees objective and efficient NOESY spectral analysis.

To obtain as accurate assignments as possible, it is a great advantage to have access to carbon-13 and nitrogen-15 NOESY experiments, since they help to resolve overlap in the proton dimension.

Researchers, using computer programs such as XPLOR-NIH,[11] CYANA, GeNMR, or RosettaNMR[21] attempt to satisfy as many of the restraints as possible, in addition to general properties of proteins such as bond lengths and angles.

Ideally, a model of a protein will be more accurate the more fit the actual molecule that represents and will be more precise as there is less uncertainty about the positions of their atoms.

Because of this fact, it has become common practice to establish the quality of NMR ensembles, by comparing it against the unique conformation determined by X-ray diffraction, for the same protein.

In addition to structures, nuclear magnetic resonance can yield information on the dynamics of various parts of the protein.

Therefore, techniques utilising relaxation measurements of carbon-13 and deuterium have recently been developed, which enables systematic studies of motions of the amino acid side-chains in proteins.

A challenging and special case of study regarding dynamics and flexibility of peptides and full-length proteins is represented by disordered structures.

This is in part caused by problems resolving overlapping peaks in larger proteins, but this has been alleviated by the introduction of isotope labelling and multidimensional experiments.

Another more serious problem is the fact that in large proteins the magnetization relaxes faster, which means there is less time to detect the signal.

[27][28] Structure determination by NMR has traditionally been a time-consuming process, requiring interactive analysis of the data by a highly trained scientist.

Several different computer programs have been published that target individual parts of the overall NMR structure determination process in an automated fashion.

So far, only the FLYA and the UNIO approach were proposed to perform the entire protein NMR structure determination process in an automated manner without any human intervention.

[29] Efforts have also been made to standardize the structure calculation protocol to make it quicker and more amenable to automation.

[30] Recently, the POKY suite, the successor of programs mentioned above, has been released to provide modern GUI tools and AI/ML features.