Molecular evolution

Molecular evolution describes how inherited DNA and/or RNA change over evolutionary time, and the consequences of this for proteins and other components of cells and organisms.

The history of molecular evolution starts in the early 20th century with comparative biochemistry, and the use of "fingerprinting" methods such as immune assays, gel electrophoresis, and paper chromatography in the 1950s to explore homologous proteins.

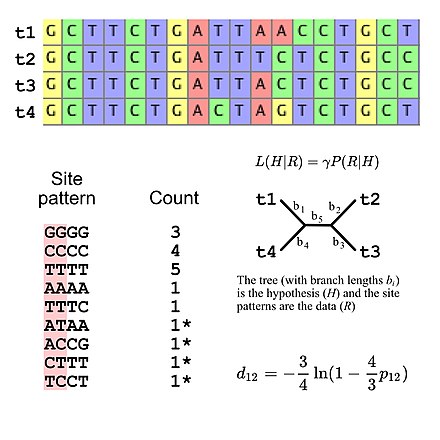

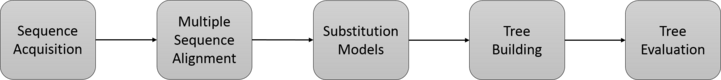

Molecular phylogenetics uses DNA, RNA, or protein sequences to resolve questions in systematics, i.e. about their correct scientific classification from the point of view of evolutionary history.

[11] In a proof-of-concept study, Bhattacharya and colleagues converted myoglobin, a non-enzymatic oxygen storage protein, into a highly efficient Kemp eliminase using only three mutations.

Change at one locus begins with a new mutation, which might become fixed due to some combination of natural selection, genetic drift, and gene conversion.

Mutations result from errors in DNA replication during cell division and by exposure to radiation, chemicals, other environmental stressors, viruses, or transposable elements.

When point mutations to just one base-pair of the DNA fall within a region coding for a protein, they are characterized by whether they are synonymous (do not change the amino acid sequence) or non-synonymous.

Other types of mutations modify larger segments of DNA and can cause duplications, insertions, deletions, inversions, and translocations.

[16] Transitions (A ↔ G or C ↔ T) are more common than transversions (purine (adenine or guanine)) ↔ pyrimidine (cytosine or thymine, or in RNA, uracil)).

A selectionist approach emphasizes e.g. that biases in codon usage are due at least in part to the ability of even weak selection to shape molecular evolution.

Rapid adaptive evolution is often found for genes involved in intragenomic conflict, sexual antagonistic coevolution, and the immune system.

Genetic drift is the change of allele frequencies from one generation to the next due to stochastic effects of random sampling in finite populations.

Many genomic features have been ascribed to accumulation of nearly neutral detrimental mutations as a result of small effective population sizes.

[25] With a smaller effective population size, a larger variety of mutations will behave as if they are neutral due to inefficiency of selection.

The dynamics of biased gene conversion resemble those of natural selection, in that a favored allele will tend to increase exponentially in frequency when rare.

Other organisms, like mammals or maize, have large amounts of repetitive DNA, long introns, and substantial spacing between genes.

Genome size, independent of gene content, correlates poorly with most physiological traits and many eukaryotes, including mammals, harbor very large amounts of repetitive DNA.

However, birds likely have experienced strong selection for reduced genome size, in response to changing energetic needs for flight.

Birds, unlike humans, produce nucleated red blood cells, and larger nuclei lead to lower levels of oxygen transport.

Indirect evidence suggests that non-avian theropod dinosaur ancestors of modern birds[28] also had reduced genome sizes, consistent with endothermy and high energetic needs for running speed.

Many bacteria have also experienced selection for small genome size, as time of replication and energy consumption are so tightly correlated with fitness.

Agrodiatus blue butterflies have diverse chromosome numbers ranging from n=10 to n=134 and additionally have one of the highest rates of speciation identified to date.

Mitochondrial and chloroplast DNA varies across taxa, but membrane-bound proteins, especially electron transport chain constituents are most often encoded in the organelle.