Quantum vortex

In most cases, quantum vortices are a type of topological defect exhibited in superfluids and superconductors.

The existence of quantum vortices was first predicted by Lars Onsager in 1949 in connection with superfluid helium.

[2] Onsager reasoned that quantisation of vorticity is a direct consequence of the existence of a superfluid order parameter as a spatially continuous wavefunction.

These ideas of Onsager were further developed by Richard Feynman in 1955[3] and in 1957 were applied to describe the magnetic phase diagram of type-II superconductors by Alexei Alexeyevich Abrikosov.

[4] In 1935 Fritz London published a very closely related work on magnetic flux quantization in superconductors.

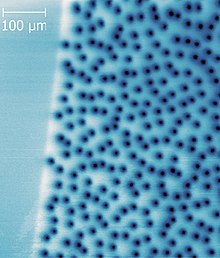

Quantum vortices are observed experimentally in type-II superconductors (the Abrikosov vortex), liquid helium, and atomic gases[5] (see Bose–Einstein condensate), as well as in photon fields (optical vortex) and exciton-polariton superfluids.

In a superfluid, a quantum vortex "carries" quantized orbital angular momentum, thus allowing the superfluid to rotate; in a superconductor, the vortex carries quantized magnetic flux.

[6][7] Under the de Broglie–Bohm theory, it is possible to derive a "velocity field" from the wave function.

In this context, quantum vortices are zeros on the wave function, around which this velocity field has a solenoidal shape, similar to that of irrotational vortex on potential flows of traditional fluid dynamics.

The circulation around any closed loop in the superfluid is zero if the region enclosed is simply connected.

Because the wave-function must return to its same value after an integer number of turns around the vortex (similar to what is described in the Bohr model), then

Thus, the circulation is quantized: A principal property of superconductors is that they expel magnetic fields; this is called the Meissner effect.

If the magnetic field becomes sufficiently strong it will, in some cases, “quench” the superconductive state by inducing a phase transition.

Over some enclosed area S, the magnetic flux is Substituting a result of London's equation:

): where ns, m, and es are, respectively, number density, mass, and charge of the Cooper pairs.

This leads to energy dissipation and causes the material to display a small amount of electrical resistance while in the superconducting state.

[8] The vortex states in ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic material are also important, mainly for information technology.

[9] They are exceptional, since in contrast to superfluids or superconducting material one has a more subtle mathematics: instead of the usual equation of the type

This leads, among other points, to the following fact: In ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic material a vortex can be moved to generate bits for information storage and recognition, corresponding, e.g., to changes of the quantum number n.[9] But although the magnetization has the usual azimuthal direction, and although one has vorticity quantization as in superfluids, as long as the circular integration lines surround the central axis at far enough perpendicular distance, this apparent vortex magnetization will change with the distance from an azimuthal direction to an upward or downward one, as soon as the vortex center is approached.

[10] As first discussed by Onsager and Feynman, if the temperature in a superfluid or a superconductor is raised, the vortex loops undergo a second-order phase transition.

This happens when the configurational entropy overcomes the Boltzmann factor, which suppresses the thermal or heat generation of vortex lines.

The ensembles of vortex lines and their phase transitions can be described efficiently by a gauge theory.

In 1949 Onsager analysed a toy model consisting of a neutral system of point vortices confined to a finite area.

[2] He was able to show that, due to the properties of two-dimensional point vortices the bounded area (and consequently, bounded phase space), allows the system to exhibit negative temperatures.

Onsager provided the first prediction that some isolated systems can exhibit negative Boltzmann temperature.

Onsager's prediction was confirmed experimentally for a system of quantum vortices in a Bose-Einstein condensate in 2019.

[11][12] In a nonlinear quantum fluid, the dynamics and configurations of the vortex cores can be studied in terms of effective vortex–vortex pair interactions.

The effective intervortex potential is predicted to affect quantum phase transitions and giving rise to different few-vortex molecules and many-body vortex patterns.

[13][14] Preliminary experiments in the specific system of exciton-polaritons fluids showed an effective attractive–repulsive intervortex dynamics between two cowinding vortices, whose attractive component can be modulated by the nonlinearity amount in the fluid.

As these phase domains merge quantum vortices can be trapped in the emerging condensate order parameter.