Queer art

[5] While historically, the term 'queer' is a homophobic slur from the 1980s AIDS crisis in the United States, it has been since re-appropriated and embraced by queer activists and integrated into many English-speaking contexts, academic or otherwise.

[9] Katz has further interpreted the use of iconography in Robert Rauschenberg's combine paintings, such as a picture of Judy Garland in Bantam (1954) and references to the Ganymede myth in Canyon (1959), as allusions to the artist's identity as a gay man.

[7] However, many queer individuals still faced pressure to remain closeted, worsened by the Hollywood Production Code which censored and banned depictions of "sex perversion" from films produced and distributed in the US up until 1968.

This became a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations by members of the LGBT+ community, and the riots are widely considered to constitute one of the most important events leading to the gay liberation movement.

In the context of the US, journalist Randy Shilts would argue in his book, And the Band Played On, that the Ronald Reagan administration put off handling the crisis due to homophobia, with the gay community being correspondingly distrustful of early reports and public health measures, resulting in the infection of hundreds of thousands more.

[7] Activist groups were a significant source of advocacy for legislation and policy change, with, for instance, the formation of ACT-UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power in 1987.

[7] The Silence=Death Project, a six-person collective, drew from influences such as feminist art activism group, Guerrilla Girls, to produce the iconic Silence = Death poster, which was wheatpasted across the city and used by ACT-UP as a central image in their activist campaign.

[17][18] Collective Gran Fury, which was established in 1988 by several members of ACT-UP, served as the organization's unofficial agitprop creator, producing guerrilla public art that drew upon the visual iconography of commercial advertisements, as seen in Kissing Doesn't Kill: Greed and Indifference Do (1989).

González-Torres' Untitled (1991) featured six black-and-white photographs of the artist's empty double bed, enlarged and posted as billboards throughout Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens in the winter of 1991.

[25] A highly personal point-of-view made public, it underscored the absence of a queer body, with the work on display after a time when González-Torres' lover, Ross Laycock, had died from AIDS-related complications in January 1991.

[25] Throughout the 1980s, the homophobic term of abuse, 'queer', began being widely used, appearing from sensationalised media reports to countercultural magazines, at bars and in zines, and showing up at alternative galleries and the occasional museum.

"[28] Activist group the Gay Liberation Front would propose queer identity as a revolutionary form of social and sexual life that could disrupt traditional notions of sex and gender.

[7] For instance, the work of Catherine Opie operates strongly within a feminist framework, further informed by her identity as a lesbian woman, though she has stated that queerness does not entirely define her practice or ideas.

[29] Since the 2000s, queer practices continue to develop and be documented internationally, with a sustained emphasis on intersectionality,[25] where one's social and political identities such as gender, race, class, sexuality, ability, among others, might come together to create unique modes of discrimination and privilege.

[32] The final photographs depict Cassils in an almost primal state, sweating, grimacing, and flying through the air as they pummel clay blocks, placing an emphasis on the physicality of their gender non-conforming and transmasculine body.

[25] In it, Huxtable inhabits a futuristic world wherein she is able to reimagine herself apart from the trauma of her childhood, where she was assigned the male gender while being raised in a conservative Baptist home in Texas.

[34] Coming shortly after the Taiwanese High Court's decision towards legalising same-sex marriage in May 2017, this would be one of the earliest art exhibitions to specifically focus on LGBTQ issues in a government-run institution in Asia.

From Jenny Holzer's Truism posters of the 1970s, to David Wojnarowicz's graffiti in the early 1980s, public space served as a politically significant venue for queer artists to display their work after years of suppression.

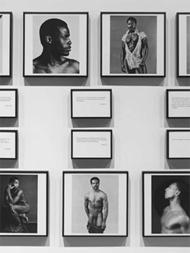

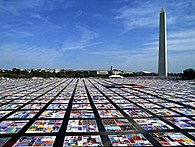

[7] Presently, people continue to add panels honouring names of lost friends, and the project has grown into various incarnations around the world, also winning a Nobel Peace Prize nomination, and raising $3 million for AIDS service organisations.

[4] Richard Meyer and Catherine Lord further argue that with the new-found acceptance of the term "queer", it runs the risk of being recuperated as "little more than a lifestyle brand or niche market", with what was once rooted in radical politics now mainstream, thus removing its transformative potential.