Romance languages

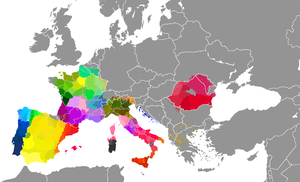

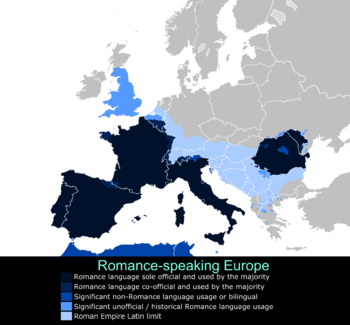

[12] In Europe, at least one Romance language is official in France, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, Luxembourg,[14] Romania, Moldova, Transnistria, Monaco, Andorra, San Marino and Vatican City.

[21][unreliable source] In Asia, Portuguese is co-official with other languages in East Timor and Macau, while most Portuguese-speakers in Asia—some 400,000[22]—are in Japan due to return immigration of Japanese Brazilians.

The native range of Romanian includes not only the Republic of Moldova, where it is the dominant language and spoken by a majority of the population, but neighboring areas in Serbia (Vojvodina and the Bor District), Bulgaria, Hungary, and Ukraine (Bukovina, Budjak) and in some villages between the Dniester and Bug rivers.

A few other languages have official recognition on a regional or otherwise limited level; for instance, Asturian and Aragonese in Spain; Mirandese in Portugal; Friulian, Sardinian and Franco-Provençal in Italy; and Romansh in Switzerland.

[This paragraph needs citation(s)] Between 350 BC and 150 AD, the expansion of the Roman Empire, together with its administrative and educational policies, made Latin the dominant native language in continental Western Europe.

British and African Romance—the forms of Vulgar Latin used in Britain and the Roman province of Africa, where it had been spoken by much of the urban population—disappeared in the Middle Ages (as did Moselle Romance in Germany).

But the Germanic tribes that had penetrated Roman Italy, Gaul, and Hispania eventually adopted Latin/Romance and the remnants of the culture of ancient Rome alongside existing inhabitants of those regions, and so Latin remained the dominant language there.

[42]: 4 Meanwhile, large-scale migrations into the Eastern Roman Empire started with the Goths and continued with Huns, Avars, Bulgars, Slavs, Pechenegs, Hungarians and Cumans.

For example, the Portuguese word fresta is descended from Latin fenestra "window" (and is thus cognate to French fenêtre, Italian finestra, Romanian fereastră and so on), but now means "skylight" and "slit".

English window, etymologically 'wind eye'), and Portuguese janela, Galician xanela, Mirandese jinela from Latin *ianuella "small opening", a derivative of ianua "door".

[11] Identifying subdivisions of the Romance languages is inherently problematic, because most of the linguistic area is a dialect continuum, and in some cases political biases can come into play.

[67] Even in Classical Latin, final -am, -em, -um (inflectional suffixes of the accusative case) were often elided in poetic meter, suggesting the m was weakly pronounced, probably marking the nasalisation of the vowel before it.

In Italo-Romance and the Eastern Romance languages, eventually all final consonants were either lost or protected by an epenthetic vowel, except for some articles and a few monosyllabic prepositions con, per, in.

In Romance languages the term 'palatalization' is used to describe the phonetic evolution of velar stops preceding a front vowel and of consonant clusters involving yod or of the palatal approximant itself.

[74] Several other consonants were "softened" in intervocalic position in Western Romance (Spanish, Portuguese, French, Northern Italian), but normally not phonemically in the rest of Italy (except some cases of "elegant" or Ecclesiastical words),[clarification needed] nor apparently at all in Romanian.

Some scholars have speculated that these sound changes may be due in part to the influence of Continental Celtic languages,[76] while scholarship of the past few decades has proposed internal motivations.

However some languages of Italy (Italian, Sardinian, Sicilian, and numerous other varieties of central and southern Italy) do have long consonants like /bb/, /dd/, /ɡɡ/, /pp/, /tt/, /kk/, /ll/, /mm/, /nn/, /rr/, /ss/, etc., where the doubling indicates either actual length or, in the case of plosives and affricates, a short hold before the consonant is released, in many cases with distinctive lexical value: e.g. note /ˈnɔte/ (notes) vs. notte /ˈnɔtte/ (night), cade /ˈkade/ (s/he, it falls) vs. cadde /ˈkadde/ (s/he, it fell), caro /ˈkaro/ (dear, expensive) vs. carro /ˈkarro/ (cart, car).

In much of central and southern Italy, the affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ weaken synchronically to fricative [ʃ] and [ʒ] between vowels, while their geminate congeners do not, e.g. cacio /ˈkatʃo/ → [ˈkaːʃo] (cheese) vs. caccio /ˈkattʃo/ → [ˈkattʃo] (I chase).

[citation needed] A number of authors remarked on this explicitly, e.g. Cicero's taunt that the populist politician Publius Clodius Pulcher had changed his name from Claudius to ingratiate himself with the masses.

[93] A few common words, however, show an early merger with ō /oː/, evidently reflecting a generalization of the popular Roman pronunciation:[citation needed] e.g. French queue, Italian coda /koda/, Occitan co(d)a, Romanian coadă (all meaning "tail") must all derive from cōda rather than Classical cauda.

[94] Similarly, Spanish oreja, Portuguese orelha, French oreille, Romanian ureche, and Sardinian olícra, orícla "ear" must derive from ōric(u)la rather than Classical auris (Occitan aurelha was probably influenced by the unrelated ausir < audīre "to hear"), and the form oricla is in fact reflected in the Appendix Probi.

During the Old French period, preconsonantal /l/ [ɫ] vocalized to /w/, producing many new falling diphthongs: e.g. dulcem "sweet" > PWR */doltsʲe/ > OF dolz /duɫts/ > douz /duts/; fallet "fails, is deficient" > OF falt > faut "is needed"; bellus "beautiful" > OF bels [bɛɫs] > beaus [bɛaws].

By the end of the Middle French period, all falling diphthongs either monophthongized or switched to rising diphthongs: proto-OF /aj ɛj jɛj ej jej wɔj oj uj al ɛl el il ɔl ol ul/ > early OF /aj ɛj i ej yj oj yj aw ɛaw ew i ɔw ow y/ > modern spelling ⟨ai ei i oi ui oi ui au eau eu i ou ou u⟩ > mod.

Already in Vulgar Latin intertonic vowels between a single consonant and a following /r/ or /l/ tended to drop: vétulum "old" > veclum > Dalmatian vieklo, Sicilian vecchiu, Portuguese velho.

Generally, those languages south and east of the La Spezia–Rimini Line (Romanian and Central-Southern Italian) maintained intertonic vowels, while those to the north and west (Western Romance) dropped all except /a/.

Some letters, notably H and Q, have been variously combined in digraphs or trigraphs (see below) to represent phonetic phenomena that could not be recorded with the basic Latin alphabet, or to get around previously established spelling conventions.

Spelling rules are typically phonemic (as opposed to being strictly phonetic); as a result of this, the actual pronunciation of standard written forms can vary substantially according to the speaker's accent (which may differ by region) or the position of a sound in the word or utterance (allophony).

Since most Romance languages have more sounds than can be accommodated in the Roman Latin alphabet they all resort to the use of digraphs and trigraphs – combinations of two or three letters with a single phonemic value.

The concept (but not the actual combinations) is derived from Classical Latin, which used, for example, TH, PH, and CH when transliterating the Greek letters "θ", "ϕ" (later "φ"), and "χ".

The phonemic contrast between geminate and single consonants is widespread in Italian, and normally indicated in the traditional orthography: fatto /fatto/ 'done' vs. fato /fato/ 'fate, destiny'; cadde /kadde/ 's/he, it fell' vs. cade /kade/ 's/he, it falls'.

• Early Middle Ages

• Early Twentieth Century