Neutrophil

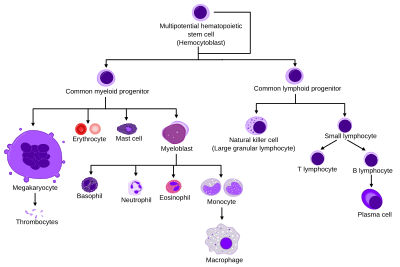

More specifically, they form the most abundant type of granulocytes and make up 40% to 70% of all white blood cells in humans.

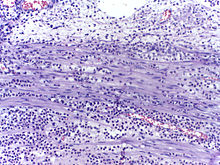

[3][4][5] The name neutrophil derives from staining characteristics on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) histological or cytological preparations.

They migrate through the blood vessels and then through interstitial space, following chemical signals such as interleukin-8 (IL-8), C5a, fMLP, leukotriene B4, and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)[10] in a process called chemotaxis.

When adhered to a surface, neutrophil granulocytes have an average diameter of 12–15 micrometers (μm) in peripheral blood smears.

[16] In the cytoplasm, the Golgi apparatus is small, mitochondria and ribosomes are sparse, and the rough endoplasmic reticulum is absent.

[22][23] Upon activation, they marginate (position themselves adjacent to the blood vessel endothelium) and undergo selectin-dependent capture followed by integrin-dependent adhesion in most cases, after which they migrate into tissues, where they survive for 1–2 days.

[citation needed] Neutrophils undergo a process called chemotaxis via amoeboid movement, which allows them to migrate toward sites of infection or inflammation.

[citation needed] Neutrophils have a variety of specific receptors, including ones for complement, cytokines like interleukins and IFN-γ, chemokines, lectins, and other proteins.

In neutrophils, lipid products of PI3Ks regulate activation of Rac1, hematopoietic Rac2, and RhoG GTPases of the Rho family and are required for cell motility.

[31] Being highly motile, neutrophils quickly congregate at a focus of infection, attracted by cytokines expressed by activated endothelium, mast cells, and macrophages.

Neutrophils express[32] and release cytokines, which in turn amplify inflammatory reactions by several other cell types.

[citation needed] In addition to recruiting and activating other cells of the immune system, neutrophils play a key role in the front-line defense against invading pathogens, and contain a broad range of proteins.

[18] They can internalize and kill many microbes, each phagocytic event resulting in the formation of a phagosome into which reactive oxygen species and hydrolytic enzymes are secreted.

[citation needed] The respiratory burst involves the activation of the enzyme NADPH oxidase, which produces large quantities of superoxide, a reactive oxygen species.

It is thought that the bactericidal properties of HClO are enough to kill bacteria phagocytosed by the neutrophil, but this may instead be a step necessary for the activation of proteases.

[36][37][38] Thus, some bacteria – and those that are predominantly intracellular pathogens – can extend the neutrophil lifespan by disrupting the normal process of spontaneous apoptosis and/or PICD (phagocytosis-induced cell death).

On the other end of the spectrum, some pathogens such as Streptococcus pyogenes are capable of altering neutrophil fate after phagocytosis by promoting rapid cell lysis and/or accelerating apoptosis to the point of secondary necrosis.

[42] The release of neutrophils by degranulation occurs through exocytosis, regulated by exocytotic machinery including SNARE proteins, RAC2, RAB27, and others.

[citation needed] In 2004, Brinkmann and colleagues described a striking observation that activation of neutrophils causes the release of web-like structures of DNA; this represents a third mechanism for killing bacteria.

It is suggested that NETs provide a high local concentration of antimicrobial components and bind, disarm, and kill microbes independent of phagocytic uptake.

Negative effects of elastase have also been shown in cases when the neutrophils are excessively activated (in otherwise healthy individuals) and release the enzyme in extracellular space.

Unregulated activity of neutrophil elastase can lead to disruption of pulmonary barrier showing symptoms corresponding with acute lung injury.

[58] The enzyme also influences activity of macrophages by cleaving their toll-like receptors (TLRs) and downregulating cytokine expression by inhibiting nuclear translocation of NF-κB.

[70] Two functionally unequal subpopulations of neutrophils were identified on the basis of different levels of their reactive oxygen metabolite generation, membrane permeability, activity of enzyme system, and ability to be inactivated.

The cells of one subpopulation with high membrane permeability (neutrophil-killers) intensively generate reactive oxygen metabolites and are inactivated in consequence of interaction with the substrate, whereas cells of another subpopulation (neutrophil-cagers) produce reactive oxygen species less intensively, don't adhere to substrate and preserve their activity.

Intravital imaging was performed in the footpad path of LysM-eGFP mice 20 minutes after infection with Listeria monocytogenes.