Nuclear fusion

[3] Quantum tunneling was discovered by Friedrich Hund in 1927,[4][5] and shortly afterwards Robert Atkinson and Fritz Houtermans used the measured masses of light elements to demonstrate that large amounts of energy could be released by fusing small nuclei.

[6] Building on the early experiments in artificial nuclear transmutation by Patrick Blackett, laboratory fusion of hydrogen isotopes was accomplished by Mark Oliphant in 1932.

The first thermonuclear weapon detonation, where the vast majority of the yield comes from fusion, was the 1952 Ivy Mike test of a liquid deuterium-fusing device.

Workable designs for a toroidal reactor that theoretically will deliver ten times more fusion energy than the amount needed to heat plasma to the required temperatures are in development (see ITER).

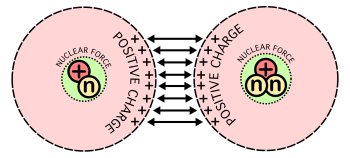

The strong force grows rapidly once the nuclei are close enough, and the fusing nucleons can essentially "fall" into each other and the result is fusion; this is an exothermic process.

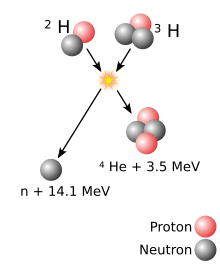

For example, the ionization energy gained by adding an electron to a hydrogen nucleus is 13.6 eV—less than one-millionth of the 17.6 MeV released in the deuterium–tritium (D–T) reaction shown in the adjacent diagram.

In the 20th century, it was recognized that the energy released from nuclear fusion reactions accounts for the longevity of stellar heat and light.

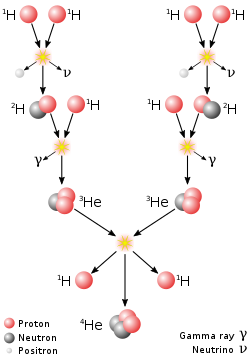

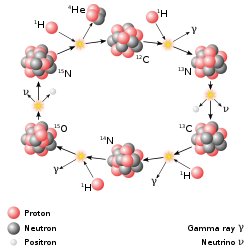

The primary source of solar energy, and that of similar size stars, is the fusion of hydrogen to form helium (the proton–proton chain reaction), which occurs at a solar-core temperature of 14 million kelvin.

So, for example, since two neutrons in a nucleus are identical to each other, the goal of distinguishing one from the other, such as which one is in the interior and which is on the surface, is in fact meaningless, and the inclusion of quantum mechanics is therefore necessary for proper calculations.

This is an extremely challenging barrier to overcome on Earth, which explains why fusion research has taken many years to reach the current advanced technical state.

[23][24] Thermonuclear fusion is the process of atomic nuclei combining or "fusing" using high temperatures to drive them close enough together for this to become possible.

Such temperatures cause the matter to become a plasma and, if confined, fusion reactions may occur due to collisions with extreme thermal kinetic energies of the particles.

After reaching sufficient temperature, given by the Lawson criterion, the energy of accidental collisions within the plasma is high enough to overcome the Coulomb barrier and the particles may fuse together.

One of the better-known attempts in the 1970s was Migma, which used a unique particle storage ring to capture ions into circular orbits and return them to the reaction area.

Theoretical calculations made during funding reviews pointed out that the system would have significant difficulty scaling up to contain enough fusion fuel to be relevant as a power source.

In the 1990s, a new arrangement using a field-reversed configuration (FRC) as the storage system was proposed by Norman Rostoker and continues to be studied by TAE Technologies as of 2021[update].

A variety of magnetic configurations exist, including the toroidal geometries of tokamaks and stellarators and open-ended mirror confinement systems.

A third confinement principle is to apply a rapid pulse of energy to a large part of the surface of a pellet of fusion fuel, causing it to simultaneously "implode" and heat to very high pressure and temperature.

[37][38] The UTIAS explosive-driven-implosion facility was used to produce stable, centred and focused hemispherical implosions[39] to generate neutrons from D-D reactions.

The other successful method was using a miniature Voitenko compressor,[40] where a plane diaphragm was driven by the implosion wave into a secondary small spherical cavity that contained pure deuterium gas at one atmosphere.

Also, fusion rates in fusors are very low due to competing physical effects, such as energy loss in the form of light radiation.

Another concern is the production of neutrons, which activate the reactor structure radiologically, but also have the advantages of allowing volumetric extraction of the fusion energy and tritium breeding.

Detailed analysis shows that this idea would not work well,[citation needed] but it is a good example of a case where the usual assumption of a Maxwellian plasma is not appropriate.

The huge size of the Sun and stars means that the x-rays produced in this process will not escape and will deposit their energy back into the plasma.

X-rays are difficult to reflect but they are effectively absorbed (and converted into heat) in less than mm thickness of stainless steel (which is part of a reactor's shield).

This will not change the optimum operating point for 21D–31T very much because the Bremsstrahlung fraction is low, but it will push the other fuels into regimes where the power density relative to 21D–31T is even lower and the required confinement even more difficult to achieve.

The probability that fusion occurs is greatly increased compared to the classical picture, thanks to the smearing of the effective radius as the de Broglie wavelength as well as quantum tunneling through the potential barrier.

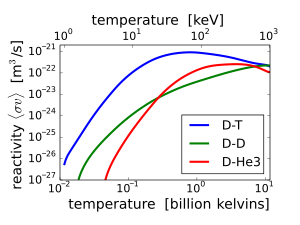

To determine the rate of fusion reactions, the value of most interest is the cross section, which describes the probability that particles will fuse by giving a characteristic area of interaction.

The Naval Research Lab's plasma physics formulary[71] gives the total cross section in barns as a function of the energy (in keV) of the incident particle towards a target ion at rest fit by the formula: Bosch-Hale[72] also reports a R-matrix calculated cross sections fitting observation data with Padé rational approximating coefficients.

The Naval Research Lab's plasma physics formulary tabulates Maxwell averaged fusion cross sections reactivities in