Wavelet

As a mathematical tool, wavelets can be used to extract information from many kinds of data, including audio signals and images.

"Complementary" wavelets decompose a signal without gaps or overlaps so that the decomposition process is mathematically reversible.

Thus, sets of complementary wavelets are useful in wavelet-based compression/decompression algorithms, where it is desirable to recover the original information with minimal loss.

In classical physics, the diffraction phenomenon is described by the Huygens–Fresnel principle that treats each point in a propagating wavefront as a collection of individual spherical wavelets.

[1] The characteristic bending pattern is most pronounced when a wave from a coherent source (such as a laser) encounters a slit/aperture that is comparable in size to its wavelength.

Multiple, closely spaced openings (e.g., a diffraction grating), can result in a complex pattern of varying intensity.

[2] The equivalent French word ondelette meaning "small wave" was used by Jean Morlet and Alex Grossmann in the early 1980s.

All wavelet transforms may be considered forms of time-frequency representation for continuous-time (analog) signals and so are related to harmonic analysis.

The wavelets forming a continuous wavelet transform (CWT) are subject to the uncertainty principle of Fourier analysis respective sampling theory:[4] given a signal with some event in it, one cannot assign simultaneously an exact time and frequency response scale to that event.

Thus, in the scaleogram of a continuous wavelet transform of this signal, such an event marks an entire region in the time-scale plane, instead of just one point.

In special situations this numerical complexity can be avoided if the scaled and shifted wavelets form a multiresolution analysis.

Time-causal wavelets representations have been developed by Szu et al [10] and Lindeberg,[11] with the latter method also involving a memory-efficient time-recursive implementation.

However, to satisfy analytical requirements (in the continuous WT) and in general for theoretical reasons, one chooses the wavelet functions from a subspace of the space

Most constructions of discrete WT make use of the multiresolution analysis, which defines the wavelet by a scaling function.

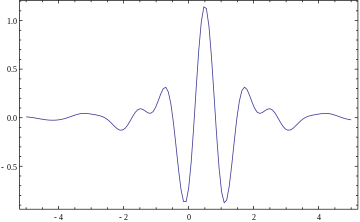

In most situations it is useful to restrict ψ to be a continuous function with a higher number M of vanishing moments, i.e. for all integer m < M

The choice of windowing function will affect the approximation error relative to the true Fourier transform.

This creates the problem that in order to cover the entire spectrum, an infinite number of levels would be required.

The development of wavelets can be linked to several separate trains of thought, starting with Alfréd Haar's work in the early 20th century.

Notable contributions to wavelet theory since then can be attributed to George Zweig’s discovery of the continuous wavelet transform (CWT) in 1975 (originally called the cochlear transform and discovered while studying the reaction of the ear to sound),[16] Pierre Goupillaud, Alex Grossmann and Jean Morlet's formulation of what is now known as the CWT (1982), Jan-Olov Strömberg's early work on discrete wavelets (1983), the Le Gall–Tabatabai (LGT) 5/3-taps non-orthogonal filter bank with linear phase (1988),[17][18][19] Ingrid Daubechies' orthogonal wavelets with compact support (1988), Stéphane Mallat's non-orthogonal multiresolution framework (1989), Ali Akansu's binomial QMF (1990), Nathalie Delprat's time-frequency interpretation of the CWT (1991), Newland's harmonic wavelet transform (1993), and set partitioning in hierarchical trees (SPIHT) developed by Amir Said with William A. Pearlman in 1996.

It uses the CDF 9/7 wavelet transform (developed by Ingrid Daubechies in 1992) for its lossy compression algorithm, and the Le Gall–Tabatabai (LGT) 5/3 discrete-time filter bank (developed by Didier Le Gall and Ali J. Tabatabai in 1988) for its lossless compression algorithm.

An important application area for generalized transforms involves systems in which high frequency resolution is crucial.

[24] Now that transmission electron microscopes are capable of providing digital images with picometer-scale information on atomic periodicity in nanostructure of all sorts, the range of pattern recognition[25] and strain[26]/metrology[27] applications for intermediate transforms with high frequency resolution (like brushlets[28] and ridgelets[29]) is growing rapidly.

This transform is capable of providing the time- and fractional-domain information simultaneously and representing signals in the time-fractional-frequency plane.

By adaptively thresholding the wavelet coefficients that correspond to undesired frequency components smoothing and/or denoising operations can be performed.

Wavelet OFDM is the basic modulation scheme used in HD-PLC (a power line communications technology developed by Panasonic), and in one of the optional modes included in the IEEE 1901 standard.

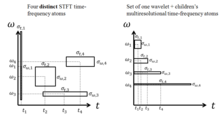

(Note that the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) is also localized in time and frequency, but there are often problems with the frequency-time resolution trade-off.

Many areas of physics have seen this paradigm shift, including molecular dynamics, chaos theory,[36] ab initio calculations, astrophysics, gravitational wave transient data analysis,[37][38] density-matrix localisation, seismology, optics, turbulence and quantum mechanics.

By setting coefficients that fall below a shrinkage threshold to zero, once the inverse transform is applied, an expectedly small amount of signal is lost due to the sparsity assumption.

Agarwal et al. proposed wavelet based advanced linear [42] and nonlinear [43] methods to construct and investigate Climate as complex networks at different timescales.

Climate networks constructed using SST datasets at different timescale averred that wavelet based multi-scale analysis of climatic processes holds the promise of better understanding the system dynamics that may be missed when processes are analyzed at one timescale only [44]