2-Norbornyl cation

Non-classical ions can be defined as organic cations in which electron density of a filled bonding orbital is shared over three or more centers and contains some sigma-bond character.

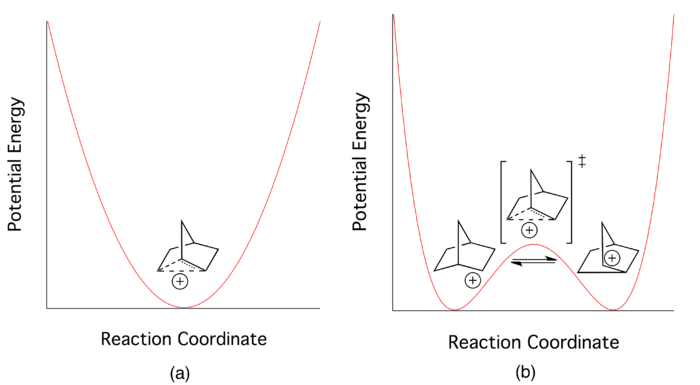

The major reason for this failure is reported to be extremely rapid forward and reverse reaction rates, which indicate a very low potential barrier for interconversion between the two enantiomers.

In one of the proposed reaction mechanisms depicted in the paper, the positive charge of an intermediate cation was not assigned to a single atom but rather to the structure as a whole.

[14] However, the term "non-classical ion" did not explicitly appear in the chemistry literature until over a decade later, when it was used to label delocalized bonding in a pyramidal, butyl cation.

[16] In 1949, Saul Winstein observed that 2-exo-norbornyl brosylate (p-bromobenzenesulfonate) and 2-endo-norbornyl tosylate (p-toluenesulfonate) gave a racemic mixture of the same product, 2-exo-norbornyl acetate, upon acetolysis (see Figure 6).

Since tosylates and brosylates work equally well as leaving groups, he concluded that both the 2-endo and 2-exo substituted norbornane must be going through a common cationic intermediate with a dominant exo reactivity.

[17] It was later shown via vapor phase chromatography that the amount of the endo epimer of product produced was less than 0.02%, proving the high stereoselectivity of the reaction.

[17] Under the non-classical description of the 2-norbornyl cation, the plane of symmetry present (running through carbons 4, 5, and 6) allow equal access to both enantiomers of the product, resulting in the observed racemic mixture.

[11] It has been shown that the major product formed from an elimination reaction of the 2-norbornyl cation is nortricyclene (not norbornene), but this has been claimed to support both non-classical ion postulates.

[18] Herbert C. Brown proposed that it was unnecessary to invoke a new type of bonding in stable intermediates to explain the reactivity of the 2-norbornyl cation.

Criticizing many chemists for disregarding past explanations of reactivity, Brown argued that all of the aforementioned information about the 2-norbornyl cation could be explained using simple steric effects present in the norbornyl system.

[2] Given that an alternative explanation using a rapidly equilibrating pair of ions for describing the 2-norbornyl cation was valid, he saw no need to invoke a stable, non-classical depiction of bonding.

[21] After publishing this controversial view in 1962, Brown began a quest to find experimental evidence incompatible with the delocalized picture of bonding in the 2-norbornyl cation.

[21][23] Though he did not rule out the possibility of a delocalized transition state Brown continued to reject the proposed reflectional symmetry of the 2-norbornyl cation, even late in his career.

In order to prove or disprove the non-classical nature of the 2-norbornyl cation, chemists on both sides of the debate zealously sought out new techniques for chemical characterization and more innovative interpretations of existing data.

[27] One spectroscopic technique that was further developed to investigate the 2-norbornyl cation was nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of compounds in highly acidic media.

These efforts motivated closer investigations of transition states and vastly increased the scientific community’s understanding of their electronic structure.

However, this formation route is much slower than that of the exo- isomer because the σ bond cannot provide anchimeric assistance for the first step, making the activation energy to the first transition state much higher.

Electron density from the π bond of the alkene moiety is donated into the σ* anti-bond between the terminal carbon and the leaving group (see Figure 8c).

[35] Raman spectra of the 2-norbornyl cation show a more symmetric species than would be expected for a pair of rapidly equilibrating classical ions.

[36] In addition, Raman spectra of the 2-norbornyl cation in some acidic solvents show an absorption band at 3110 cm-1 indicative of an electron-depleted cyclopropane ring.

Since the major difference between these two reversible rearrangements is the amount of delocalization possible in the electronic ground state, one can attribute the stabilization of the 3-methyl-2-norbornyl cation to its non-classical nature.

Tertiary carbocations are much more stable than their secondary counterparts and therefore do not need to adopt delocalized bonding in order to reach the lowest possible potential energy.

By systematically decomposing the 2-norbornyl cation and analyzing the amount of radioactive isotope in each decomposition product, researchers were able to show further evidence for the non-classical picture of delocalized bonding (see Figure 9).

If a system is undergoing a rapid equilibrium at a rate faster than the timescale of a 13C NMR experiment, the relevant peak will be split dramatically (on the order of 10-100 ppm).

[46][47] The 13C NMR spectrum of the 2-norbornyl cation at -150 °C shows that the peaks corresponding to carbons 1 and 2 are split by less than 10 ppm (parts per million) when this experiment is carried out, indicating that the system is not undergoing a rapid equilibrium as in the classical picture.