Academic art

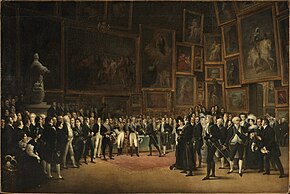

In this period, the standards of the French Académie des Beaux-Arts were very influential, combining elements of Neoclassicism and Romanticism, with Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres a key figure in the formation of the style in painting.

They wielded significant influence due to their association with state power, often acting as conduits for the dissemination of artistic, political, and social ideals, by deciding what was considered "official art".

[1][2][3] The Accademia's fame spread quickly, to the point that, within just five months of its founding, important Venetian artists such as Titian, Salviati, Tintoretto and Palladio applied for admission, and in 1567, King Philip II of Spain consulted it about plans for El Escorial.

However, if on the one hand the artists did rise socially, on the other they lost the security of market insertion that the guild system provided, having to live in the uncertain expectation of individual protection by some patron.

Together, they made it the main executive arm of a program to glorify the king's absolutist monarchy, definitively establishing the school's association with the State and thereby vesting it with enormous directive power over the entire national art system, which contributed to making France the new European cultural center, displacing the hitherto Italian supremacy.

[19] At the end of Louis XIV's reign, the academic style and teachings strongly associated with his monarchy began to spread throughout Europe, accompanying the growth of the urban nobility.

[20][21] The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, founded in 1754, may be taken as a successful example in a smaller country, which achieved its aim of producing a national school and reducing the reliance on imported artists.

[24] Meanwhile, back in Italy, another major center of irradiation appeared, Venice, launching the tradition of urban views and "capriccios", fantasy landscape scenes populated by ancient ruins, which became favorites of noble travelers on the Grand Tour.

For them, academicism had become an outdated model, excessively rigid and dogmatic; they criticized the methodology, which they believed produced an art that was merely servile to ancient examples, and condemned the institutional administration, which they considered corrupt and despotic.

Quatremère de Quincy, the secretary of the new Institut, which had been born as an apparatus of revolutionary renewal, paradoxically believed that art schools served to preserve traditions, not to found new ones.

[25] The greatest innovations he introduced were the idea of reunifying the arts under an atmosphere of egalitarianism, eliminating honorary titles for members and some other privileges, and his attempt to make administration more transparent, eminently public and functional.

Theories of the importance of both line and color asserted that through these elements an artist exerts control over the medium to create psychological effects, in which themes, emotions, and ideas can be represented.

[30][31] The historical genre, the most appreciated, included works that conveyed themes of an inspirational and ennobling nature, essentially with an ethical background, consistent with the tradition founded by masters such as Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci.

[32] With the cooling of the libertarian ardor of the first Romantics, with the final failure of Napoleon's imperialist project, and with the popularization of an eclectic style that blended Romanticism and Neoclassicism, adapting them to the purposes of the bourgeoisie, which became one of the greatest sponsors of the arts, the emergence of a general feeling of resignation appeared, as well as a growing prevalence of individual bourgeois taste against idealistic collective systems.

[34][35][36] As a result of this great cultural transformation, the academic educational model, in order to survive, had to incorporate some of these innovations, but it broadly maintained the established tradition, and managed to become even more influential, continuing to inspire not only Europe, but also America and other countries colonized by Europeans, throughout the 19th century.

[37] Another factor in this academic revival, even in the face of a profoundly changing scenario, was the reiteration of the idea of art as an instrument of political affirmation by nationalist movements in several countries.

In the first half of the 19th century, the Royal Academy already exercised direct or indirect control over a vast network of galleries, museums, exhibitions and other artistic societies, and over a complex of administrative agencies that included the Crown, parliament and other state departments, which found their cultural expression through their relations with the academic institution.

Around 1860, it was again stabilized through new strategies of monopolizing power, incorporating new trends into its orbit, such as promoting the previously ignored technique of watercolor, which had become vastly popular, accepting the admission of women, requiring new members in an enlarged membership to renounce their affiliation to other societies and reforming its administrative structure to appear as a private institution, but imbued with a civic purpose and a public character.

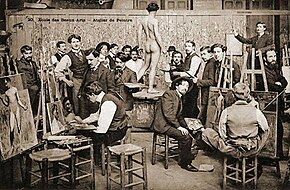

Under their influence, masterclasses were introduced—paradoxically within the academies themselves—which sought to group promising students around a master, who was responsible for their instruction, but with much more concentrated attention and care than in the more generalist French system, based on the assumption that such more individualized treatment could provide a stronger and deeper education.

Some of the leading local artists studied in London under the guidance of the Royal Academy and others, who settled in England, continued to exert influence in their home country through regular submissions of works of art.

This was the case with John Singleton Copley, the dominant influence in his country until the beginning of the 19th century, and also with Benjamin West, who became one of the leaders of the English neoclassical-romantic movement and one of the main European names of his generation in the field of history painting.

Cole and Durand were also the founders of the Hudson River School, an aesthetic movement that began a great painting tradition, lasting for three generations, with a remarkable unity of principles, and which presented the national landscape in an epic, idealistic and sometimes fanciful light.

[51][52] Italy offered a historical and cultural backdrop of irresistible interest to sculptors, with priceless monuments, ruins and collections, and working conditions were infinitely superior to those of the New World, where there was a shortage of both marble and capable assistants to help the artist in the complex and laborious art of stone carving and bronze casting.

By this time, the United States had already established its culture and created the general conditions to promote consistent and high-level local sculptural production, adopting an eclectic synthesis of styles.

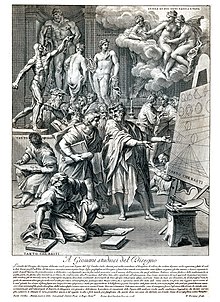

The academies had as a basic assumption the idea that art could be taught through its systematization into a fully communicable body of theory and practice, minimizing the importance of creativity as an entirely original and individual contribution.

[68] Academic art was first criticized for its use of idealism, by Realist artists such as Gustave Courbet, as being based on idealistic clichés and representing mythical and legendary motives while contemporary social concerns were being ignored.

[72] Even with this concession, the public reaction was negative,[73] and an anonymous review published at the time summarizes the general attitude: This exhibition is sad and grotesque... save for one or two questionable exceptions, there is not a single work that deserves the honor of being shown in the official galleries.

Even several of the most important modern artists, such as Kandinsky, Klee, Malevich and Moholy-Nagy, dedicated themselves to creating schools and formulating new theories for art education based on these ideas, most notably the Bauhaus, founded in Weimar, Germany, in 1919 by Walter Gropius.

Art historian Paul Barlow stated that despite the wide dissemination of modernism at the beginning of the 20th century, the theoretical bases of its rejection of academicism were surprisingly little explored by its proponents, forming above all a kind of "anti-academic myth", more than a consistent critique.

[86] Of all those engaged in this study, Nikolaus Pevsner was perhaps the most important, describing in the 1940s the history of academies on an epic scale, but focusing on the institutional and organizational aspects, disconnecting them from the aesthetic and geographical ones.