History of Armenia

In the Bronze Age, several states flourished in the Armenian highlands, including the Hittite Empire (at the height of its power), Mitanni (southwestern historical Armenia), and Hayasa-Azzi (1600–1200 BC).

The earliest evidence for this culture is found on the Ararat plain; thence it spread to Georgia by 3000 BC (but never reaching Colchis), proceeding westward and to the south-east into an area below the Urmia basin and Lake Van.

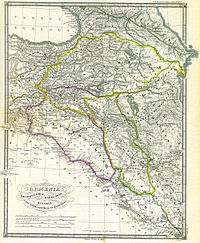

[45] At its zenith, from 95 to 66 BC, Greater Armenia extended its rule over parts of the Caucasus and the area that is now eastern and central Turkey, north-western Iran, Israel, Syria and Lebanon, forming the second Armenian empire.

Despite being a military defeat, the Battle of Avarayr and the subsequent guerilla war in Armenia eventually resulted in the Treaty of Nvarsak (484), which guaranteed religious freedom to the Armenians.

[81] Although the native Bagratuni dynasty was founded under favourable circumstances, the feudal system gradually weakened the country by eroding loyalty to the central government.

To escape death or servitude at the hands of those who had assassinated his relative Gagik II, King of Ani, an Armenian named Roupen with some of his countrymen went into the gorges of the Taurus Mountains and then into Tarsus of Cilicia.

Two great dynastic families, the Rubenids and the Hethumids, ruled what became in 1199, with the coronation of Levon I, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and through skillful diplomacy and military alliances (explained below) maintained their political autonomy until 1375.

[88] World powers, such as Byzantium, the Holy Roman Empire, the papacy and even the Abbasid caliph competed and vied for influence over the state and each raced to be the first to recognise Leo II, Prince of Lesser Armenia, as the rightful king.

The Shah pursued a careful strategy, advancing and retreating as the occasion demanded, determined not to risk his enterprise in a direct confrontation with stronger enemy forces.

The Shah had previously ordered the destruction of the only bridge, so people were forced into the waters, where a great many drowned, carried away by the currents, before reaching the opposite bank.

One eye-witness, Father de Guyan, describes the predicament of the refugees thus: Unable to maintain his army on the desolate plain, Sinan Pasha was forced to winter in Van.

In 1804, Pavel Tsitsianov invaded the Iranian town of Ganja and massacred many of its inhabitants while making the rest flee deeper within the borders of Qajar Iran.

The Treaty of Gulistan that was signed in the same year forced Qajar Iran to irrevocably cede significant amounts of its Caucasian territories to Russia, comprising modern-day Dagestan, Georgia, and most of what is today the Republic of Azerbaijan.

The Armenian subjects of the Russian Empire lived in relative safety, compared to their Ottoman kin, albeit clashes with Tatars and Kurds were frequent in the early 20th century.

The Armenian-American historian George Bournoutian gives a summary of the ethnic make-up after those events:[107] In the first quarter of the 19th century the Khanate of Erevan included most of Eastern Armenia and covered an area of approximately 7,000 square miles [18,000 km2].

[108] As a result of which an estimated 57,000 Armenian refugees from Persia returned to the territory of the Erivan Khanate after 1828, while about 35,000 Muslims (Persians, Turkic groups, Kurds, Lezgis, etc.)

On 24 April 1915, Ottoman authorities rounded up, arrested, and deported 235 to 270 Armenian intellectuals and community leaders from Constantinople to the region of Ankara, where the majority were murdered.

The genocide was carried out during and after World War I and implemented in two phases—the wholesale killing of the able-bodied male population through massacre and subjection of army conscripts to forced labour, followed by the deportation of women, children, the elderly, and the infirm on death marches leading to the Syrian Desert.

[121] A considerable degree of hostility existed between Armenia and its new neighbor to the east, the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan, stemming largely from racial, religious, cultural and societal differences.

Although the borders of the two countries were still undefined, Azerbaijan claimed most of the territory Armenia was sitting on, demanding all or most parts of the former Russian provinces of Elizavetpol, Tiflis, Yerevan, Kars and Batum.

[122] As diplomacy failed to accomplish compromise, even with the mediation of the commanders of a British expeditionary force that had installed itself in the Caucasus, territorial clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan took place throughout 1919 and 1920, most notably in the regions of Nakhichevan, Karabakh, and Syunik (Zangezur).

Mustafa Kemal Pasha had sent several delegations to Moscow in search of an alliance, where he had found a receptive response by the Soviet government, which started sending gold and weapons to the Turkish revolutionaries, which would prove disastrous for the Armenians.

[131] Finally, on the following day, 6 December, Felix Dzerzhinsky's Cheka entered Yerevan, thus effectively ending the existence of the Democratic Republic of Armenia.

Any individual who was suspected of using or introducing nationalist, racist and conservative rhetoric or elements in their works were labelled traitors or propagandists, and were sent to prisons in Siberia.

Even Zabel Yesayan, a writer who was fortunate enough to escape from ethnic cleansing during the Armenian genocide, was quickly exiled to Siberia after returning to Armenia from France.

The harsh situation caused by the earthquake and subsequent events made many residents of Armenia leave and settle in North America, Western Europe and Australia.

Following the Armenian victory in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, both Azerbaijan and Turkey closed their borders and imposed a blockade which they retain to this day, severely affecting the economy of the fledgling republic.

The plan, accepted by Ter-Petrosyan and Azerbaijan, called for a "phased" or "step-by-step" settlement of the conflict which would postpone an agreement on Nagorno-Karabakh's status, the main stumbling block.

[142] Contrary to the initial optimism, the Rambouillet talks did not produce any agreement, with key issues such as the status of Nagorno-Karabakh and whether Armenian troops would withdraw from Kalbajar still being contentious.

The declaration, which Pashinyan described as a coup attempt, caused a political crisis that ended with the Chief of the General Staff of the Armenian Armed Forces Onik Gasparyan's dismissal.

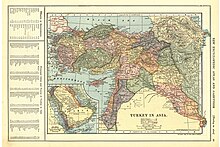

Orange: areas overwhelmingly populated by Armenians (Republic of Armenia: 98%; [ 133 ] Nagorno-Karabakh: 99%; Javakheti: 95%)

Yellow: Historically Armenian areas with presently no or insignificant Armenian population (Western Armenia and Nakhichevan)