Biological basis of personality

Animal models of behavior, molecular biology, and brain imaging techniques have provided some insight into human personality, especially trait theories.

Much of the current understanding of personality from a neurobiological perspective places an emphasis on the biochemistry of the behavioral systems of reward, motivation, and punishment.

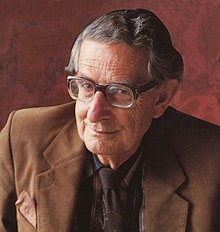

[2] However, the most cited and influential figures in publishing the first biology-based personality theories are Hans Eysenck and Jeffrey Alan Gray.

Gray, a student of Eysenck, studied personality traits as individual differences in sensitivity to rewarding and punishing stimuli.

[4] In 1951, Hans Eysenck and Donald Prell published an experiment in which identical (monozygotic) and fraternal (dizygotic) twins, ages 11 and 12, were tested for neuroticism.

It is described in detail in an article published in the Journal of Mental Science in which Eysenck and Prell concluded that "The factor of neuroticism is not a statistical artifact, but constitutes a biological unit which is inherited as a whole ... neurotic predisposition is to a large extent hereditarily determined.

[8] This allowed for presenting and sharing of ideas between psychologists, psychiatrists, molecular geneticists, and neuroscientists, and eventually gave birth to the book under the same title.

Gray's reinforcement sensitivity theory (RST) is based on the idea that there are three brain systems that all differently respond to rewarding and punishing stimuli.

This method involves collecting data for a large number of genes simultaneously which provides many advantages in studying personality.

In an article written by Alison M. Bell and Nadia Aubin-Horth, they describe the advantages very clearly by stating, "For one, it is probable that the genetic basis of personality is polygenic, so it makes sense to simultaneously study many genes.

On a broad level, this involves the autonomic nervous system, fear-processing circuits in the amygdala, the reward pathway from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex.

All of these circuits heavily rely on neurotransmitters and their precursors, but there has been the most research support for dopamine and serotonin pathways: Previous studies show that genes account for at most 50 percent of a given trait.

[20] With the growing interest in using molecular genetics in tracing the biological basis of personality,[8] there may be more gene-trait links found in the future.

Conscientiousness was associated with increased volume in the lateral prefrontal cortex, a region involved in planning and the voluntary control of behavior.

[23] A separate study also reported a significant association between neuroticism scores and gray matter volume of the left amygdala.

A separate but similar line of research has used diffusion tensor imaging to measure the structural integrity of white matter in the brain.

Such studies have demonstrated associations between single brain regions' neural responses to certain tasks and individual differences in a wide range of sociocognitive functioning, such as approach/avoidance behavior,[27] sensitivity to rejection,[28] conceptions of the self,[29][30] and susceptibility to persuasive messages.

[31] A small collection of fMRI studies have also demonstrated a significant relationship between brain responses to certain tasks and personality survey measures, such as extraversion and neuroticism.

For example, it is unlikely that neural activation in a single brain region is unilaterally associated with individual differences in personality measures, such as the tendency to down-regulate negative emotions.

[42] For example, a recent line of research has demonstrated that individual differences in functional connectomes, which are characterized by patterns of spontaneous synchronization of neural activations across the entire brain, are predictive of individual differences in personality and sociocognitive functioning, such as openness to experience,[43] fluid intelligence,[44] and trait levels of paranoia.

[48][49] The default mode network, for example, is composed of regions such as the medial prefrontal cortex, angular gyrus, temporoparietal junction, and the hippocampus, to name a few.

[42] To address this gap, neuroscience researchers have begun to leverage graph theoretical approaches to better understand characteristics of these brain networks, such as their assortativity, efficiency, and modularity.

For example, one study has demonstrated that individual differences in anxiety-related harm avoidance behavior was associated with relatively low efficiency (i.e., high path length) in the insular-opercular brain network at rest.

This finding suggests that trait anxiety may be associated with relatively slow and inefficient transfer of information within the insular-opercular brain network.