Chronic electrode implant

Applications for stimulating interfaces include sensory prosthetics (cochlear implants), for example, are the most successful variety of sensory prosthetics) and deep brain stimulation therapies, while recording interfaces can be used for research applications[11] and to record the activity of speech or motor centers directly from the brain.

In principle these systems are susceptible to the same tissue response that causes failure in implanted electrodes, but stimulating interfaces can overcome this problem by increasing signal strength.

They suggest four directions for improvment:[12][13] This review will focus on techniques pursued in the literature that are relevant to achieving the goal of consistent, long-term recordings.

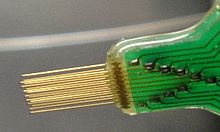

[14][15][16][17][18][19][20] In addition to the variety of materials used, electrodes are constructed in many different shapes,[21] including planar shanks, simple uniform microwires, and probes that taper to a thin tip from a wider base.

Qualitative assessments of vascular damage were made by taking real-time images of electrodes being inserted into 500 um thick coronal brain slices.

Fluorescent microbeads lodged throughout the tissue, providing discrete coordinates that aided in computerized calculations of strain and deformation.

Analysis of the images prompted the division of tissue damage into 4 categories: Fluid displacement by device insertion frequently resulted in ruptured vessels.

When implanted in neural tissue in the long term, microelectrodes stimulate a sort of foreign body response, primarily effected by astrocytes and microglia.

"Current theories hold that glial encapsulation, i.e. gliosis, insulates the electrode from nearby neurons, thereby hindering diffusion and increasing impedance, extends the distance between the electrode and its nearest target neurons, or creates an inhibitory environment for neurite extension, thus repelling regenerating neural processes away from recording sites".

ED1+ reading is indicative of the presence of macrophages, and was observed in a densely packed region within approximately 50 μm of the electrode surface.

Studies have demonstrated that surfaces functionalized with sequences taken from adhesive peptides will decrease cellular motility and support higher neuronal populations.

Some notable success has also been made in developing microfluid delivery mechanisms that could ostensibly deliver targeted pharmacological agents to electrode implantation sites to alleviate the tissue response.

The goal of these tools is to provide a powerful, objective way of analyzing the failure of chronic neural electrodes in order to improve the reliability of the technology.

Midbrains are surgically removed from day 14 Fischer 344 rats and grown in culture to create a confluent layer of neurons, microglia, and astrocytes.

The goal of this model is not to detail the electrical or chemical characteristics of the interface, but the mechanical ones created by electrode-tissue adhesion, tethering forces, and strain mismatch.

[44] For studies requiring a massive quantity of identical electrodes, a bench-top technique has been demonstrated in the literature to use a silicon shape as a master to produce multiple copies out of polymeric materials via a PDMS intermediate.