Covalent bond

The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms, when they share electrons, is known as covalent bonding.

[4] The prefix co- means jointly, associated in action, partnered to a lesser degree, etc.

Thus, covalent bonding does not necessarily require that the two atoms be of the same elements, only that they be of comparable electronegativity.

Covalent bonding that entails the sharing of electrons over more than two atoms is said to be delocalized.

The term covalence in regard to bonding was first used in 1919 by Irving Langmuir in a Journal of the American Chemical Society article entitled "The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules".

Langmuir wrote that "we shall denote by the term covalence the number of pairs of electrons that a given atom shares with its neighbors.

"[6] The idea of covalent bonding can be traced several years before 1919 to Gilbert N. Lewis, who in 1916 described the sharing of electron pairs between atoms[7] (and in 1926 he also coined the term "photon" for the smallest unit of radiant energy).

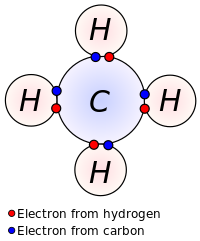

An alternative form of representation, not shown here, has bond-forming electron pairs represented as solid lines.

[9] While the idea of shared electron pairs provides an effective qualitative picture of covalent bonding, quantum mechanics is needed to understand the nature of these bonds and predict the structures and properties of simple molecules.

Walter Heitler and Fritz London are credited with the first successful quantum mechanical explanation of a chemical bond (molecular hydrogen) in 1927.

Pi (π) bonds are weaker and are due to lateral overlap between p (or d) orbitals.

However polarity also requires geometric asymmetry, or else dipoles may cancel out, resulting in a non-polar molecule.

Macromolecular structures have large numbers of atoms linked by covalent bonds in chains, including synthetic polymers such as polyethylene and nylon, and biopolymers such as proteins and starch.

In organic chemistry, when a molecule with a planar ring obeys Hückel's rule, where the number of π electrons fit the formula 4n + 2 (where n is an integer), it attains extra stability and symmetry.

These occupy three delocalized π molecular orbitals (molecular orbital theory) or form conjugate π bonds in two resonance structures that linearly combine (valence bond theory), creating a regular hexagon exhibiting a greater stabilization than the hypothetical 1,3,5-cyclohexatriene.

[9] In the case of heterocyclic aromatics and substituted benzenes, the electronegativity differences between different parts of the ring may dominate the chemical behavior of aromatic ring bonds, which otherwise are equivalent.

[9] Certain molecules such as xenon difluoride and sulfur hexafluoride have higher coordination numbers than would be possible due to strictly covalent bonding according to the octet rule.

A more recent quantum description[17] is given in terms of atomic contributions to the electronic density of states.

[18] For valence bond theory, the atomic hybrid orbitals are filled with electrons first to produce a fully bonded valence configuration, followed by performing a linear combination of contributing structures (resonance) if there are several of them.

[8] The two approaches are regarded as complementary, and each provides its own insights into the problem of chemical bonding.

Simple (Heitler–London) valence bond theory correctly predicts the dissociation of homonuclear diatomic molecules into separate atoms, while simple (Hartree–Fock) molecular orbital theory incorrectly predicts dissociation into a mixture of atoms and ions.

On the other hand, simple molecular orbital theory correctly predicts Hückel's rule of aromaticity, while simple valence bond theory incorrectly predicts that cyclobutadiene has larger resonance energy than benzene.

[20] Although the wavefunctions generated by both theories at the qualitative level do not agree and do not match the stabilization energy by experiment, they can be corrected by configuration interaction.

[18] Modern calculations in quantum chemistry usually start from (but ultimately go far beyond) a molecular orbital rather than a valence bond approach, not because of any intrinsic superiority in the former but rather because the MO approach is more readily adapted to numerical computations.

[23] To overcome this issue, an alternative formulation of the bond covalency can be provided in this way.

of the solid where the outer sum runs over all atoms A of the unit cell.

If the range to select is unclear, it can be identified in practice by examining the molecular orbitals that describe the electron density along with the considered bond.

levels of atom B is given as where the contributions of the magnetic and spin quantum numbers are summed.

the higher the overlap of the selected atomic bands, and thus the electron density described by those orbitals gives a more covalent A−B bond.

An analogous effect to covalent binding is believed to occur in some nuclear systems, with the difference that the shared fermions are quarks rather than electrons.