Dnipro

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Dnipro rapidly developed as a logistical hub for humanitarian aid and a reception point for people fleeing the various battle fronts.

[32] According to archeological finds, in the Paleolithic period (7—3 thousand Anno Domini) human settlements appear near the Aptekarska brook [uk] in what is now Chechelivskyi District and on Monastyrskyi Island.

[34][35] During the Migration Period (300–800) nomadic tribes of the Huns, Avars, Bulgarians, and Magyars passed through the lands of the Dnieper region, they came into contact with local agricultural East Slavs.

[37] In 1635, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth built the Kodak Fortress above the Dnieper Rapids at Kodaky on the south-eastern outskirts of modern Dnipro near the current Kaidatsky Bridge,[19] only to have it destroyed within months by the Cossacks of Ivan Sulyma.

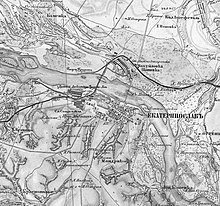

[37] On 22 January 1784 Russian Empress Catherine the Great signed an Imperial Ukase directing that "the gubernatorial city under name of Yekaterinoslav be moved to the right bank of the Dnieper river near Kodak".

9 May] 1787, in the course of her celebrated Crimean journey, the Empress laid the foundation stone of the Transfiguration Cathedral in the presence of Austrian Emperor Joseph II, Polish king Stanisław August Poniatowski, and the French and English ambassadors.

[50][49] While into the late nineteenth century the principal business of the town remained the processing of agricultural raw materials,[15] there was an early state-sponsored effort to promote manufacture.

[58] In the widespread social unrest that followed the 1905 defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, the political life of the city was dominated by the revolutionary opposition (including the Jewish Workers Socialist Party and the Bund)[58] and by the insurrectionary spirit of the nascent labor movement.

[62] Due to intense political agitation the newly formed factory committees and professional unions by autumn of 1917 mainly supported the Bolsheviks, significantly strengthening their positions.

[62] On 12 February they declared Yekaterinoslav part of a Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic, but the following month, under the terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, conceded the territory to the German and Austrian-allied UPR.

On 18 May 1918 the Hetman of the Ukrainian State, Pavlo Skoropadskyi, ordered the previously nationalized enterprises returned to their former owners, and with the assistance of Austro-Hungarian troops the new authorities suppressed labor protest.

Following this, many organizations and institutions began to name Yekaterinoslav Krasnodniprovsk in official documents, only to be reminded in the press that the renaming of settlements could only be decided by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet.

[78] As early as July 1944, the State Committee of Defence in Moscow decided to build a large military machine-building factory in Dnipropetrovsk on the location of the pre-war aircraft plant.

[78] Notwithstanding the high-security regime, in September and October 1972, workers downed tools in several factories in Dnipropetrovsk demanding higher wages, better food and living conditions, and the right to choose one's job.

[99] In the 1980s, by which time the KGB had conceded that their raids against "hippies" had failed suppress the youth rebellion,[100][nb 5] such behaviour was reportedly found in an admixture of Anglo-American" heavy metal, punk rock and Banderism—the veneration of Stepan Bandera, and of other Ukrainian nationalists, who in the Soviet narrative were denounced and discredited as Nazi collaborators.

Some of the activists involved in this "disco movement" went on in the 1980s to engage in their own illicit tourist and music enterprises, and several later became influential figures in Ukrainian national politics, among them Yulia Tymoshenko, Victor Pinchuk, Serhiy Tihipko, Ihor Kolomoyskyi and Oleksandr Turchynov.

[103] During Stalin's Great Purge, Leonid Brezhnev rose rapidly within the ranks of the local nomenklatura,[104] from director of the Dnipropetrovsk Metallurgical Institute in 1936 to regional (Obkom) Party Secretary in charge of the city's defence industries in 1939.

Opposition politicians claimed to see the hand of President Viktor Yanukovych intent on disrupting the October 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary election and installing a presidential regime.

[138] In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, and with developing military fronts near Kyiv and to the north, east and south, Dnipro has become a logistical hub for humanitarian aid and a reception point for people fleeing the war.

[citation needed] At the same time, its control of a Dnieper River crossing and the opportunity it would provide to cut off Ukrainian forces in the Donbas makes the city a high-value target for the Russians.

[168][169] Kuchma was also closely tied to another budding Dnipropetrovsk billionaire, his son-in-law Viktor Pinchuk whose assets included several giant steel and pipe plants in the region and the bank Kredit-Dnepr.

In the loop of a major meander, the Dnieper changes its course from the north west to continue southerly and later south-westerly through Ukraine, ultimately passing Kherson, where it finally flows into the Black Sea.

However, according to other schemes (such as the Salvador Rivas-Martínez bioclimatic one), Dnipro has a Supratemperate bioclimate, and belongs to the Temperate xeric steppic thermoclimatic belt, due to high evapotranspiration.

[219] This is one of the main reasons why much of Dnipro's central avenue, Akademik Yavornitskyi Prospekt (formerly Karl Marx Prospect), is designed in the style of Stalinist Social Realism.

[221] The Grand Hotel Ukraine survived the war but was later simplified much in design, with its roof being reconstructed in a typical French mansard style as opposed to the ornamental Ukrainian Baroque of the pre-war era.

After the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 and the appointment of Nikita Khrushchev as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the industrialisation of Dnipropetrovsk became even more profound, with the Southern (Yuzhne) Missile and Rocket factory being set up in the city.

[232] On 31 January 2024 92 other toponyms were renamed by the Dnipro City Council, including the avenue named after (Soviet cosmonaut and first human in space) Yuri Gagarin.

[249] It has several facilities devoted to heavy industry that produce a wide range of products, including cast-iron, launch vehicles, rolled metal, pipes, machinery, different mining combines, agricultural equipment, tractors, trolleybuses, refrigerators, different chemicals and many others.

Privat Group controls thousands of companies of virtually every industry in Ukraine, European Union, Georgia, Ghana, Russia, Romania, United States and other countries.

Domestic connections exist between Dnipro and Kyiv, Lviv, Odesa, Ivano-Frankivsk, Truskavets, Kharkiv and many other smaller Ukrainian cities, while international destinations include, among others the Bulgarian seaside resort of Varna.