Epigenetics in learning and memory

Another hypothesis is that changes in DNA methylation that occur even early in life can persist through adulthood, affecting how genes are able to be activated in response to different environmental cues.

The first demonstration about the role of epigenetics in learning in memory was the landmark work of Szyf and Meaney (PMID 15220929) where they showed that licking and grooming by mother rats (maternal care) prevented methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene.

Miller and Sweatt demonstrated that rats trained in a contextual fear conditioning paradigm had elevated levels of mRNA for DNMT3a and DNMT3b in the hippocampus.

However, when rats were treated with the DNMT inhibitors zebularine or 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine immediately after fear-conditioning, they demonstrated reduced learning (freezing behavior).

[6] The memory suppressor gene, protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), was shown to have increased CpG island methylation after contextual-fear conditioning.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), another important gene in neural plasticity, has also been shown to have reduced methylation and increased transcription in animals that have undergone learning.

[7] While these studies have been linked to the hippocampus, recent evidence has also shown increased demethylation of reelin and BDNF in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), an area involved in cognition and emotion.

[9] Mice that have genetic disruptions for CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) have been shown to have significant problems in hippocampus#Role in memory-dependent memory and have impaired hippocampal LTP.

[2] Changes in expression of genes associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is characterized by an impaired extinction of traumatic memory, may be mediated by DNA methylation.

[10] In people with schizophrenia, it has been shown that reelin is down-regulated through increased DNA methylation at promoter regions in GABAergic interneurons.

[13] In these experiments by Gupta et al., a connection was made between changes in histone methylation and active gene expression during the consolidation of associative memories.

[13] The change in methylation state of histones at the location of specific gene promoters, as opposed to just genome-wide, is also involved in memory formation.

[15] One study examined the role of G9a/GLP-mediated transcriptional silencing in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex (EC) during memory consolidation.

[16] In addition, G9a/GLP inhibition in the entorhinal cortex altered histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation in the Cornu Ammonis area 1 of the hippocampus, suggesting the importance of this complex in mediating connectivity between these two brain regions.

Therefore, the G9a/GLP complex plays an important role in histone methylation and long-term memory formation in the hippocampus and the EC.

This acetylation code can then be read and provide generous information for the study of inheritance patterns of epigenetic changes like that of learning, memory and disease states.

Studies with histone deactylase complex inhibitors like SAHA, toluene, garcinol, trichostatin A and sodium butyrate have shown that acetylation is important for the synaptic plasticity of the brain; by inhibiting deactylase complexes total acetylation rates in the brain increased leading to increased rates of transcription and enhanced memory consolidation.

The proposed mechanism for how this cascade works is that MAPK regulates histone acetylation and subsequent chromatin remodeling by means of downstream effectors, such as the CREB binding protein (which has HAT activity).

CREB then recruits a HAT to help create and stabilize the long term formation of memory, often through the self-perpetuation of acetylated histones.

Studies conclude that HDAC inhibitors such as trichostatin A (TSA) increase histone acetylation and improve synaptic plasticity and long-term memory (Fig 1A).

CREB, a cAMP response element-binding protein and transcriptional activator, binds CBP forming the CREBP complex.

The KIX domain allows for interaction between CREB and CBP, so knocking out this region disrupts formation of the CREBP complex.

Other memory-deficit disorders which may involve HDAC inhibitors as potential therapy are: During a new learning experience, a set of genes is rapidly expressed in the brain.

DNA topoisomerase II beta (TOP2B) activity is essential for the expression of IEGs in a type of learning experience in mice termed associative fear memory.

[27] Such a learning experience appears to rapidly trigger TOP2B to induce double-strand breaks in the promoter DNA of IEG genes that function in neuroplasticity.

[31] The double-strand break introduced by TOP2B apparently frees the part of the promoter at an RNA polymerase-bound transcription start site to physically move to its associated enhancer (see regulatory sequence).

[33] As reviewed by Massaad and Klann in 2011[35] and by Beckhauser et al. in 2016,[36] reactive oxygen species (ROS) are required for normal learning and memory functions.

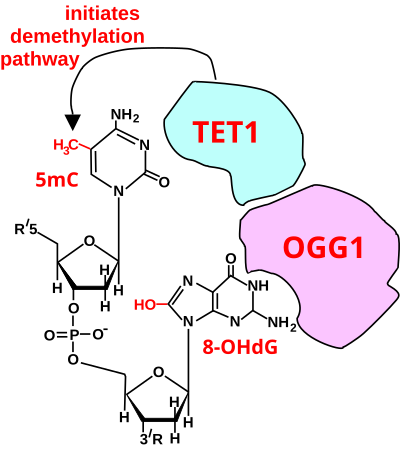

[40][41] In particular, heterozygous OGG1+/- mice, with about half the protein level of OGG1, exhibit poorer learning performance in the Barnes maze compared to wild-type animals.

The presence of 5mC at CpG sites in gene promoters is widely considered to be an epigenetic mark that acts to suppress transcription.

The pattern of induced and repressed genes within neurons appears to provide a molecular basis for forming this first transient memory of this training event in the hippocampus of the rat brain.