Gas

The only chemical elements that are stable diatomic homonuclear molecular gases at STP are hydrogen (H2), nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2), and two halogens: fluorine (F2) and chlorine (Cl2).

[6] Van Helmont's word appears to have been simply a phonetic transcription of the Ancient Greek word χάος 'chaos' – the g in Dutch being pronounced like ch in "loch" (voiceless velar fricative, /x/) – in which case Van Helmont simply was following the established alchemical usage first attested in the works of Paracelsus.

[9] In contrast, the French-American historian Jacques Barzun speculated that Van Helmont had borrowed the word from the German Gäscht, meaning the froth resulting from fermentation.

[10] Because most gases are difficult to observe directly, they are described through the use of four physical properties or macroscopic characteristics: pressure, volume, number of particles (chemists group them by moles) and temperature.

These four characteristics were repeatedly observed by scientists such as Robert Boyle, Jacques Charles, John Dalton, Joseph Gay-Lussac and Amedeo Avogadro for a variety of gases in various settings.

Transient, randomly induced charges exist across non-polar covalent bonds of molecules and electrostatic interactions caused by them are referred to as Van der Waals forces.

This particle separation and size influences optical properties of gases as can be found in the following list of refractive indices.

The resulting statistical analysis of this sample size produces the "average" behavior (i.e. velocity, temperature or pressure) of all the gas particles within the region.

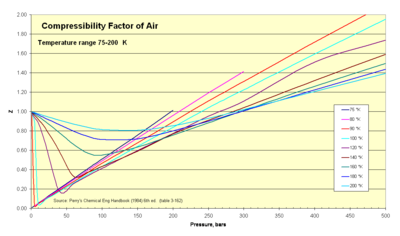

However, the high technology equipment in use today was designed to help us safely explore the more exotic operating environments where the gases no longer behave in an "ideal" manner.

This advanced math, including statistics and multivariable calculus, adapted to the conditions of the gas system in question, makes it possible to solve such complex dynamic situations as space vehicle reentry.

Within this volume, it is sometimes easier to visualize the gas particles moving in straight lines until they collide with the container (see diagram at top).

The volume of the balloon in the video shrinks when the trapped gas particles slow down with the addition of extremely cold nitrogen.

Thermal (kinetic) energy added to a gas or liquid (an endothermic process) produces translational, rotational, and vibrational motion.

In contrast, a solid can only increase its internal energy by exciting additional vibrational modes, as the crystal lattice structure prevents both translational and rotational motion.

For gases, the density can vary over a wide range because the particles are free to move closer together when constrained by pressure or volume.

The kinetic theory of gases, which makes the assumption that these collisions are perfectly elastic, does not account for intermolecular forces of attraction and repulsion.

Likewise, the macroscopically measurable quantity of temperature, is a quantification of the overall amount of motion, or kinetic energy that the particles exhibit.

The use of statistical mechanics and the partition function is an important tool throughout all of physical chemistry, because it is the key to connection between the microscopic states of a system and the macroscopic variables which we can measure, such as temperature, pressure, heat capacity, internal energy, enthalpy, and entropy, just to name a few.

However, if you were to isothermally compress this cold gas into a small volume, forcing the molecules into close proximity, and raising the pressure, the repulsions will begin to dominate over the attractions, as the rate at which collisions are happening will increase significantly.

If two molecules are moving at high speeds, in arbitrary directions, along non-intersecting paths, then they will not spend enough time in proximity to be affected by the attractive London-dispersion force.

This approximation is more suitable for applications in engineering although simpler models can be used to produce a "ball-park" range as to where the real solution should lie.

At the upper end of the engine temperature ranges (e.g. combustor sections – 1300 K), the complex fuel particles absorb internal energy by means of rotations and vibrations that cause their specific heats to vary from those of diatomic molecules and noble gases.

Examples where real gas effects would have a significant impact would be on the Space Shuttle re-entry where extremely high temperatures and pressures were present or the gases produced during geological events as in the image of the 1990 eruption of Mount Redoubt.

Stated as a formula, thus is: Because the before and after volumes and pressures of the fixed amount of gas, where the before and after temperatures are the same both equal the constant k, they can be related by the equation:

In 1787, the French physicist and balloon pioneer, Jacques Charles, found that oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and air expand to the same extent over the same 80 kelvin interval.

He noted that, for an ideal gas at constant pressure, the volume is directly proportional to its temperature: In 1802, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac published results of similar, though more extensive experiments.

Mathematically, this can be represented for n species as: The image of Dalton's journal depicts symbology he used as shorthand to record the path he followed.

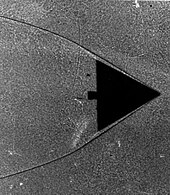

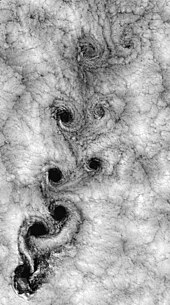

The delta wing image clearly shows the boundary layer thickening as the gas flows from right to left along the leading edge.

A study of the delta wing in the Schlieren image reveals that the gas particles stick to one another (see Boundary layer section).

A container of ice allowed to melt at room temperature takes hours, while in semiconductors the heat transfer that occurs in the device transition from an on to off state could be on the order of a few nanoseconds.