Geomorphology

Geomorphology (from Ancient Greek γῆ (gê) 'earth' μορφή (morphḗ) 'form' and λόγος (lógos) 'study')[2] is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topographic and bathymetric features generated by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or near Earth's surface.

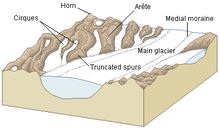

Surface processes comprise the action of water, wind, ice, wildfire, and life on the surface of the Earth, along with chemical reactions that form soils and alter material properties, the stability and rate of change of topography under the force of gravity, and other factors, such as (in the very recent past) human alteration of the landscape.

Fluvial geomorphologists focus on rivers, how they transport sediment, migrate across the landscape, cut into bedrock, respond to environmental and tectonic changes, and interact with humans.

[7] Practical applications of geomorphology include hazard assessment (such as landslide prediction and mitigation), river control and stream restoration, and coastal protection.

Indications of effects of wind, fluvial, glacial, mass wasting, meteor impact, tectonics and volcanic processes are studied.

In the 5th century BC, Greek historian Herodotus argued from observations of soils that the Nile delta was actively growing into the Mediterranean Sea, and estimated its age.

[13] The medieval Persian Muslim scholar Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (973–1048), after observing rock formations at the mouths of rivers, hypothesized that the Indian Ocean once covered all of India.

Noticing bivalve shells running in a horizontal span along the cut section of a cliffside, he theorized that the cliff was once the pre-historic location of a seashore that had shifted hundreds of miles over the centuries.

Scholar-official Du Yu (222–285) of the Western Jin dynasty predicted that two monumental stelae recording his achievements, one buried at the foot of a mountain and the other erected at the top, would eventually change their relative positions over time as would hills and valleys.

[13] Daoist alchemist Ge Hong (284–364) created a fictional dialogue where the immortal Magu explained that the territory of the East China Sea was once a land filled with mulberry trees.

Keith Tinkler has suggested that the word came into general use in English, German and French after John Wesley Powell and W. J. McGee used it during the International Geological Conference of 1891.

[22] John Edward Marr in his The Scientific Study of Scenery[23] considered his book as, 'an Introductory Treatise on Geomorphology, a subject which has sprung from the union of Geology and Geography'.

In the decades following Davis's development of this idea, many of those studying geomorphology sought to fit their findings into this framework, known today as "Davisian".

[24] Davis's ideas are of historical importance, but have been largely superseded today, mainly due to their lack of predictive power and qualitative nature.

[26] Both Davis and Penck were trying to place the study of the evolution of the Earth's surface on a more generalized, globally relevant footing than it had been previously.

In the early 19th century, authors – especially in Europe – had tended to attribute the form of landscapes to local climate, and in particular to the specific effects of glaciation and periglacial processes.

[citation needed] In the period following World War II, the emergence of process, climatic, and quantitative studies led to a preference by many earth scientists for the term "geomorphology" in order to suggest an analytical approach to landscapes rather than a descriptive one.

[28] During the age of New Imperialism in the late 19th century European explorers and scientists traveled across the globe bringing descriptions of landscapes and landforms.

Following the early work of Grove Karl Gilbert around the turn of the 20th century,[11][24][25] a group of mainly American natural scientists, geologists and hydraulic engineers including William Walden Rubey, Ralph Alger Bagnold, Hans Albert Einstein, Frank Ahnert, John Hack, Luna Leopold, A. Shields, Thomas Maddock, Arthur Strahler, Stanley Schumm, and Ronald Shreve began to research the form of landscape elements such as rivers and hillslopes by taking systematic, direct, quantitative measurements of aspects of them and investigating the scaling of these measurements.

[11][24][25][34] These methods began to allow prediction of the past and future behavior of landscapes from present observations, and were later to develop into the modern trend of a highly quantitative approach to geomorphic problems.

[37] Quantitative geomorphology can involve fluid dynamics and solid mechanics, geomorphometry, laboratory studies, field measurements, theoretical work, and full landscape evolution modeling.

These approaches are used to understand weathering and the formation of soils, sediment transport, landscape change, and the interactions between climate, tectonics, erosion, and deposition.

[38][39] In Sweden Filip Hjulström's doctoral thesis, "The River Fyris" (1935), contained one of the first quantitative studies of geomorphological processes ever published.

[46] In contrast to its disputed status in geomorphology, the cycle of erosion model is a common approach used to establish denudation chronologies, and is thus an important concept in the science of historical geology.

[49][50] Geomorphically relevant processes generally fall into (1) the production of regolith by weathering and erosion, (2) the transport of that material, and (3) its eventual deposition.

Winds may erode, transport, and deposit materials, and are effective agents in regions with sparse vegetation and a large supply of fine, unconsolidated sediments.

[51] The interaction of living organisms with landforms, or biogeomorphologic processes, can be of many different forms, and is probably of profound importance for the terrestrial geomorphic system as a whole.

Terrestrial landscapes in which the role of biology in mediating surface processes can be definitively excluded are extremely rare, but may hold important information for understanding the geomorphology of other planets, such as Mars.

[57] Soil, regolith, and rock move downslope under the force of gravity via creep, slides, flows, topples, and falls.

The action of volcanoes tends to rejuvenize landscapes, covering the old land surface with lava and tephra, releasing pyroclastic material and forcing rivers through new paths.