History of Islam

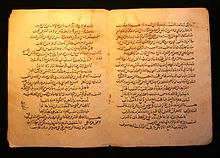

[4][5][6] According to the traditional account,[2][3][7] the Islamic prophet Muhammad began receiving what Muslims consider to be divine revelations in 610 CE, calling for submission to the one God, preparation for the imminent Last Judgement, and charity for the poor and needy.

[5][Note 2] In 622 CE Muhammad migrated to the city of Yathrib (now known as Medina), where he began to unify the tribes of Arabia under Islam,[9] returning to Mecca to take control in 630[10][11] and order the destruction of all pagan idols.

[12][13] By the time Muhammad died c. 11 AH (632 CE), almost all the tribes of the Arabian Peninsula had converted to Islam,[14] but disagreement broke out over who would succeed him as leader of the Muslim community during the Rashidun Caliphate.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, destructive Mongol invasions, along with the loss of population due to the Black Death, greatly weakened the traditional centers of the Muslim world, stretching from Persia to Egypt, but saw the emergence of the Timurid Renaissance and major economic powers such as the Mali Empire in West Africa and the Bengal Sultanate in South Asia.

[3] Some of their efforts to win independence and build modern nation-states over the course of the last two centuries continue to reverberate to the present day, as well as fuel conflict-zones in the MENA region, such as Afghanistan, Central Africa, Chechnya, Iraq, Kashmir, Libya, Palestine, Syria, Somalia, Xinjiang, and Yemen.

[41] The school included scholars such as John Wansbrough and his students Andrew Rippin, Norman Calder, G. R. Hawting, Patricia Crone, and Michael Cook, as well as Günter Lüling, Yehuda D. Nevo, and Christoph Luxenberg.

For example, during the later stages of the Abbasid Caliphate, even the capital city of Baghdad was effectively ruled by other dynasties such as the Buyyids and the Seljuks, while the Ottoman Turks commonly delegated executive authority over outlying provinces to local potentates, such as the Deys of Algiers, the Beys of Tunis, and the Mamluks of Iraq.

These inspirations urged him to proclaim a strict monotheistic faith, as the final expression of Biblical prophetism earlier codified in the sacred texts of Judaism and Christianity; to warn his compatriots of the impending Judgement Day; and to castigate social injustices of his city.

[5][64] In 622 CE, a few years after losing protection with the death of his influential uncle ʾAbū Ṭālib ibn ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib, Muhammad migrated to the city of Yathrib (subsequently called Medina) where he was joined by his followers.

[66] In Yathrib, where he was accepted as an arbitrator among the different communities of the city under the terms of the Constitution of Medina, Muhammad began to lay the foundations of the new Islamic society, with the help of new Quranic verses which provided guidance on matters of law and religious observance.

[66] In the time remaining until his death in 632 CE, tribal chiefs across the Arabian peninsula entered into various agreements with him, some under terms of alliance, others acknowledging his claims of prophethood and agreeing to follow Islamic practices, including paying the alms levy to his government, which consisted of a number of deputies, an army of believers, and a public treasury.

Was he solely an Arab nationalist—a political genius intent upon uniting the proliferation of tribal clans under the banner of a new religion—or was his vision a truly international one, encompassing a desire to produce a reformed humanity in the midst of a new world order?

Muhammad's closest companions (ṣaḥāba), the four "rightly-guided" caliphs who succeeded him, continued to expand the Islamic empire to encompass Jerusalem, Ctesiphon, and Damascus, and sending Arab Muslim armies as far as the Sindh region.

[7][72] A number of tribal Arab leaders refused to extend the agreements made with Muhammad to Abū Bakr, ceasing payments of the alms levy and in some cases claiming to be prophets in their own right.

[73] By the end of the reign of the second caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb, the Arab Muslim armies, whose battle-hardened ranks were now swelled by the defeated rebels[74] and former imperial auxiliary troops,[75] invaded the eastern Byzantine provinces of Syria and Egypt, while the Sasanids lost their western territories, with the rest of Persia to follow soon afterwards.

[84] The expansion was partially halted between 638 and 639 CE during the years of great famine and plague in Arabia and the Levant, respectively, but by the end of ʿUmar's reign, Syria, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and much of Persia were incorporated into the early Islamic empire.

[104] Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī, by then Muhammad's only surviving grandson, refused to swear allegiance to the Umayyads; he was killed in the Battle of Karbala the same year, in an event still mourned by Shīʿa Muslims on the Day of Ashura.

Additionally the Bayt al-mal and the Welfare State expenses to assist the Muslim and the non-Muslim poor, needy, elderly, orphans, widows, and the disabled, increased, the Umayyads asked the new converts (mawali) to continue paying the poll tax.

[112][113] The descendants of Muhammad's uncle Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib rallied discontented mawali, poor Arabs, and some Shi'a against the Umayyads and overthrew them with the help of the general Abu Muslim, inaugurating the Abbasid dynasty in 750, which moved the capital to Baghdad.

At the end of the Early Baghdad Abbasids period, Empress Zoe Karbonopsina pressed for an armistice with Al-Muqtadir and arranged for the ransom of the Muslim prisoner[158] while the Byzantine frontier was threatened by Bulgarians.

The Banu Mazyad (Mazyadid State) general, Dubays ibn Sadaqa[165] (emir of Al-Hilla), plundered Bosra and attacked Baghdad together with a young brother of the sultan, Ghiyath ad-Din Mas'ud.

The dynasty was founded in 909 by ʻAbdullāh al-Mahdī Billah, who legitimized his claim through descent from Muhammad by way of his daughter Fātima as-Zahra and her husband ʻAlī ibn-Abī-Tālib, the first Shīʻa Imām, hence the name al-Fātimiyyūn "Fatimid".

[202] Feeling threatened by the Crusaders and the Mongols, ibn Taymiyya called for elimination by a militant jihād against whom he deemed "heretic", including Shias, al-Ashʿariyya and falāsifa (philosophers),[203] and established his own theological doctrines.

[204] Having a deep-rooting discern for the Mongols, ibn Taimiyya sought to pronounce takfīr (excommunication) upon the Turco-Mongol rulers, despite their profession of the shahada (Islamic testimony of faith), or regular observance of aṣ-Ṣalāh (obligatory prayers), sawm (fasting) and other expressions of religiosity.

[227] The Mamluks, who were slave-soldiers predominantly of Turkic, Caucasian, and Southeastern European origins[228][229][230] (see Saqaliba), forced out the Mongols (see Battle of Ain Jalut) after the final destruction of the Ayyubid dynasty.

[269] In the early 16th century, the Shiʿite Safavid dynasty assumed control in Persia under the leadership of Shah Ismail I, defeating the ruling Turcoman federation Aq Qoyunlu (also called the "White Sheep Turkomans") in 1501.

Suleiman I advanced deep into Hungary following the Battle of Mohács in 1526 – reaching as far as the gates of Vienna thereafter, and signed a Franco-Ottoman alliance with Francis I of France against Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire 10 years later.

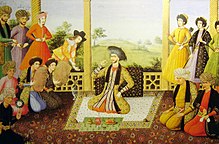

The tradition of Persian miniature painting in manuscripts reached its peak, until Tahmasp turned to strict religious observance in middle age, prohibiting the consumption of alcohol and hashish and removing casinos, taverns, and brothels.

He transformed Turkish culture to reflect European laws, adopted Arabic numerals, the Latin script, separated the religious establishment from the state, and emancipated woman—even giving them the right to vote in parallel with women's suffrage in the west.

[327][328] Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait (despite being hostile to Iraq) encouraged Saddam Hussein to invade Iran,[329] which resulted in the Iran–Iraq War, as they feared that an Islamic revolution would take place within their own borders.

Cairo, Egypt; south of Bab Al-Futuh

"Islamic Cairo" building was named after Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah , built by Fatimid vizier Gawhar Al-Siqilli , and extended by Badr al-Jamali .

List of Crusades

Early period

· First Crusade 1095–1099

· Second Crusade 1147–1149

· Third Crusade 1187–1192

Low Period

· Fourth Crusade 1202–1204

· Fifth Crusade 1217–1221

· Sixth Crusade 1228–1229

Late period

· Seventh Crusade 1248–1254

· Eighth Crusade 1270

· Ninth Crusade 1271–1272