Science in the medieval Islamic world

Other subjects of scientific inquiry included alchemy and chemistry, botany and agronomy, geography and cartography, ophthalmology, pharmacology, physics, and zoology.

Islamic mathematicians such as Al-Khwarizmi, Avicenna and Jamshīd al-Kāshī made advances in algebra, trigonometry, geometry and Arabic numerals.

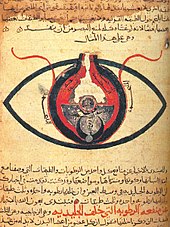

Islamic physicists such as Ibn Al-Haytham, Al-Bīrūnī and others studied optics and mechanics as well as astronomy, and criticised Aristotle's view of motion.

Islamic armies eventually conquered Arabia, Egypt and Mesopotamia, and successfully displaced the Persian and Byzantine Empires from the region within a few decades.

The Islamic Golden Age (roughly between 786 and 1258) spanned the period of the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258), with stable political structures and flourishing trade.

[1][2] From the 9th century onwards, scholars such as Al-Kindi[3] translated Indian, Assyrian, Sasanian (Persian) and Greek knowledge, including the works of Aristotle, into Arabic.

[4] Islamic science survived the initial Christian reconquest of Spain, including the fall of Seville in 1248, as work continued in the eastern centres (such as in Persia).

[8] The Emerald Tablet, a cryptic text that all later alchemists up to and including Isaac Newton saw as the foundation of their art, first occurs in the Sirr al-khalīqa and in one of the works attributed to Jabir.

[9] In practical chemistry, the works of Jabir, and those of the Persian alchemist and physician Abu Bakr al-Razi (c. 865–925), contain the earliest systematic classifications of chemical substances.

Another was astrology, predicting events affecting human life and selecting suitable times for actions such as going to war or founding a city.

He constructed a water clock in Toledo, discovered that the Sun's apogee moves slowly relative to the fixed stars, and obtained a good estimate of its motion[14] for its rate of change.

The thirteenth century encyclopedia compiled by Zakariya al-Qazwini (1203–1283) – ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt (The Wonders of Creation) – contained, among many other topics, both realistic botany and fantastic accounts.

[18][17][19] The use and cultivation of plants was documented in the 11th century by Muhammad bin Ibrāhīm Ibn Bassāl of Toledo in his book Dīwān al-filāha (The Court of Agriculture), and by Ibn al-'Awwam al-Ishbīlī (also called Abū l-Khayr al-Ishbīlī) of Seville in his 12th century book Kitāb al-Filāha (Treatise on Agriculture).

Ibn Bassāl had travelled widely across the Islamic world, returning with a detailed knowledge of agronomy that fed into the Arab Agricultural Revolution.

[21] Abu Zayd al-Balkhi (850–934), founder of the Balkhī school of cartography in Baghdad, wrote an atlas called Figures of the Regions (Suwar al-aqalim).

He also wrote the Tabula Rogeriana (Book of Roger), a geographic study of the peoples, climates, resources and industries of the whole of the world known at that time.

[25] Islamic mathematicians gathered, organised and clarified the mathematics they inherited from ancient Egypt, Greece, India, Mesopotamia and Persia, and went on to make innovations of their own.

Early in the Abbasid caliphate (founded 750), soon after the foundation of Baghdad in 762, some mathematical knowledge was assimilated by al-Mansur's group of scientists from the pre-Islamic Persian tradition in astronomy.

Astronomers from India were invited to the court of the caliph in the late eighth century; they explained the rudimentary trigonometrical techniques used in Indian astronomy.

[26][27][28] Al-Khwarizmi (8th–9th centuries) was instrumental in the adoption of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system and the development of algebra, introduced methods of simplifying equations, and used Euclidean geometry in his proofs.

[32]: 14 Ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (801–873) worked on cryptography for the Abbasid Caliphate,[33] and gave the first known recorded explanation of cryptanalysis and the first description of the method of frequency analysis.

[40] Sometime around the seventh century, Islamic scholars adopted the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, describing their use in a standard type of text fī l-ḥisāb al hindī, (On the numbers of the Indians).

Its physicians inherited knowledge and traditional medical beliefs from the civilisations of classical Greece, Rome, Syria, Persia and India.

Al-Haytham proposed in his Book of Optics that vision occurs by way of light rays forming a cone with its vertex at the center of the eye.

[57] He was also an early proponent of the scientific method, the concept that a hypothesis must be proved by experiments based on confirmable procedures or mathematical evidence, five centuries before Renaissance scientists.

Al-Muwaffaq, in the 10th century, wrote The foundations of the true properties of Remedies, describing chemicals such as arsenious oxide and silicic acid.

Works by Masawaih al-Mardini (c. 925–1015) and by Ibn al-Wafid (1008–1074) were printed in Latin more than fifty times, appearing as De Medicinis universalibus et particularibus by Mesue the Younger (died 1015) and as the Medicamentis simplicibus by Abenguefit (c. 997 – 1074) respectively.

[65] The fields of physics studied in this period, apart from optics and astronomy which are described separately, are aspects of mechanics: statics, dynamics, kinematics and motion.

In the eleventh century Ibn Sina adopted roughly the same idea, namely that a moving object has force which is dissipated by external agents like air resistance.

[67] As a non-Aristotelian suggestion, it was essentially abandoned until it was described as "impetus" by Jean Buridan (c. 1295–1363), who was likely influenced by Ibn Sina's Book of Healing.