Isolobal principle

In organometallic chemistry, the isolobal principle (more formally known as the isolobal analogy) is a strategy used to relate the structure of organic and inorganic molecular fragments in order to predict bonding properties of organometallic compounds.

For his work on the isolobal analogy, Hoffmann was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1981, which he shared with Kenichi Fukui.

[3] In his Nobel Prize lecture, Hoffmann stressed that the isolobal analogy is a useful, yet simple, model and thus is bound to fail in certain instances.

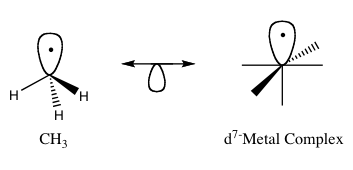

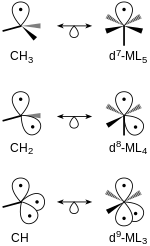

The molecule retains its molecular geometry as the frontier orbital points in the direction of the missing hydrogen atom.

The isolobal fragments of octahedral complexes, such as type ML6, can be created in a similar fashion.

However, removing a ligand to form the first frontier orbital would result in a MoL−5 complex because Mo has obtained an additional electron making it d7.

To remedy this, Mo can be exchanged for Mn, which would form a neutral d7 complex in this case, as shown in Figure 3.

For example, consider Figure 5, which shows the production of frontier orbitals in tetrahedral and octahedral molecules.

[7] The isolobal analogy can also be used with isoelectronic fragments having the same coordination number, which allows charged species to be considered.

Assuming ligands act as two-electron donors the metal center in square-planar molecules is d8.