Italian Renaissance painting

The Early Renaissance style was started by Masaccio and then further developed by Fra Angelico, Paolo Uccello, Piero della Francesca, Sandro Botticelli, Verrocchio, Domenico Ghirlandaio, and Giovanni Bellini.

The High Renaissance period was that of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Andrea del Sarto, Coreggio, Giorgione, the latter works of Giovanni Bellini, and Titian.

Unlike those of his Byzantine contemporaries, Giotto's figures are solidly three-dimensional; they stand squarely on the ground, have discernible anatomy and are clothed in garments with weight and structure.

The inevitability of death, the rewards for the penitent and the penalties of sin were emphasised in a number of frescoes, remarkable for their grim depictions of suffering and their surreal images of the torments of Hell.

Giusto's masterpiece, the decoration of the Padua Baptistery, follows the theme of humanity's Creation, Downfall, and Salvation, also having a rare Apocalypse cycle in the small chancel.

[10] In Florence, at the Spanish Chapel of Santa Maria Novella, Andrea di Bonaiuto was commissioned to emphasise the role of the Church in the redemptive process, and that of the Dominican Order in particular.

The style is fully developed in the works of Simone Martini and Gentile da Fabriano, which have an elegance and a richness of detail, and an idealised quality not compatible with the starker realities of Giotto's paintings.

In the Brancacci Chapel, his Tribute Money fresco has a single vanishing point and uses a strong contrast between light and dark to convey a three-dimensional quality to the work.

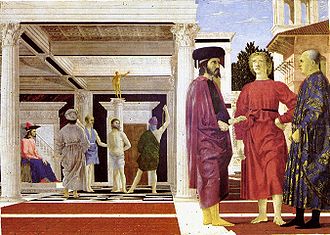

[13] During the first half of the 15th century, the achieving of the effect of realistic space in a painting by the employment of linear perspective was a major preoccupation of many painters, as well as the architects Brunelleschi and Alberti who both theorised about the subject.

Brunelleschi is known to have done a number of careful studies of the piazza and octagonal baptistery outside Florence Cathedral and it is thought he aided Masaccio in the creation of his famous trompe-l'œil niche around the Holy Trinity he painted at Santa Maria Novella.

One of the most influential painters of northern Italy was Andrea Mantegna of Padua, who had the good fortune to be in his teen years at the time in which the great Florentine sculptor Donatello was working there.

He also worked on the high altar and created a series of bronze panels in which he achieved a remarkable illusion of depth, with perspective in the architectural settings and apparent roundness of the human form all in very shallow relief.

Unfortunately, the building was mostly destroyed during World War II, and they are only known from photographs which reveal an already highly developed sense of perspective and a knowledge of antiquity, for which the ancient University of Padua had become well known, early in the 15th century.

The one concession is the scattering of jolly winged putti, who hold up plaques and garlands and clamber on the illusionistic pierced balustrade that surrounds a trompe-l'œil view of the sky that decks the ceiling of the chamber.

[12] Mantegna's main legacy in considered the introduction of spatial illusionism, carried out by a mastery of perspective, both in frescoes and in sacra conversazione paintings: his tradition of ceiling decoration was followed for almost three centuries.

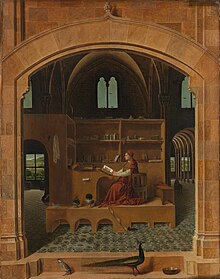

The composition of the small painting is framed by a late Gothic arch, through which is viewed an interior, domestic on one side and ecclesiastic on the other, in the centre of which the saint sits in a wooden corral surrounded by his possessions while his lion prowls in the shadows on the floor.

The highly flexibly medium of oils, which could be made opaque or transparent, and allowed alteration and additions for days after it had been laid down, opened a new world of possibility to Italian artists.

But the most influential aspect of the triptych was the extremely natural and lifelike quality of the three shepherds with stubbly beards, workworn hands and expressions ranging from adoration to wonder to incomprehension.

[26] The High Renaissance of painting was the culmination of the varied means of expression[27] and various advances in painting technique, such as linear perspective,[28] the realistic depiction of both physical[29] and psychological features,[30] and the manipulation of light and darkness, including tone contrast, sfumato (softening the transition between colours) and chiaroscuro (contrast between light and dark),[31] in a single unifying style[32] which expressed total compositional order, balance and harmony.

Many other Renaissance artists painted versions of the Last Supper, but only Leonardo's was destined to be reproduced countless times in wood, alabaster, plaster, lithograph, tapestry, crochet, and table-carpets.

In his paintings such as the Mona Lisa (c. 1503–1517) and Virgin of the Rocks (1483–1486) (the earliest complete work fully of his hand), he used light and shade with such subtlety that, for want of a better word, it became known as Leonardo's sfumato or "smoke".

Another significant work of Leonardo's was The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (c. 1503–1519); the monumental three-dimensional quality of the group and the calculated effects of dynamism and tension in the composition made it a model that inspired Classicists and the Mannerists in equal measure.

The rounded forms and luminous colours of Perugino, the lifelike portraiture of Ghirlandaio, the realism and lighting of Leonardo, and the powerful draughtsmanship of Michelangelo became unified in the paintings of Raphael.

This fresco depicts a meeting of all the most learned ancient Athenians, gathered in a grand classical setting around the central figure of Plato, whom Raphael has famously modelled upon Leonardo da Vinci.

Over and over he painted, in slightly different poses, a similar plump, calm-faced blonde woman and her chubby babies the most famous probably being La Belle Jardinière ("The Madonna of the Beautiful Garden"), now in the Louvre.

His larger work, the Sistine Madonna, used as a design for countless stained glass windows, has come, in the 21st century, to provide the iconic image of two small cherubs which has been reproduced on everything from paper table napkins to umbrellas.

[99] One art scholar states that in the latter, Correggio creates a “dazzling illusion: the architecture of the dome seems to dissolve and the form seems to explode through the building drawing the viewer up into the swirling vortex of saints and angels who rush upwards to accompany the Virgin in to heaven.”[100] In those domes and other works, his bold use of perspective, usually by setting a dark colour against light colours to enhance the illusion of depth, is described as astonishing.

[112] In the 1520s, he remained faithful to the ideals of the High Renaissance, such as in paintings’ compositions,[113] and with the faces of his figures usually being calm and often beautiful, showing none of the torment of his Mannerist contemporaries,[114] some of whom were his pupils.

[16] Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling and later The Last Judgment had direct influence on the figurative compositions firstly of Raphael and his pupils and then almost every subsequent 16th-century painter who looked for new and interesting ways to depict the human form.

It is possible to trace his style of figurative composition through Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo, Bronzino, Parmigianino, Veronese, to el Greco, Carracci, Caravaggio, Rubens, Poussin and Tiepolo to both the Classical and the Romantic painters of the 19th century such as Jacques-Louis David and Delacroix.