First Jewish–Roman War

[24] Nonetheless, most Jews were not affiliated with any particular group and practiced common traditions such as observing the Shabbat, celebrating holidays, attending synagogue, making pilgrimages to the Temple, following dietary laws, and circumcising their newborn males.

[39] Religious fanaticism grew, inspiring figures like Theudas, who sought to part the Jordan but was executed by procurator Fadus,[40] and "The Egyptian" who led followers toward Jerusalem before being dispersed by Antonius Felix.

[69] Philip Alexander similarly defined the "Zealots" as a coalition of various factions that, despite internal divisions, were united under a shared form of Jewish nationalism—the Fourth Philosophy—and a common goal of forcefully liberating Israel.

[70] Some scholars suggest that apocalyptic beliefs played a role in fueling the revolt, with many rebels envisioning a divinely sanctioned cosmic struggle inspired by prophetic texts, such as the Book of Daniel, which foretold the fall of the fourth imperial power, which people believed was Rome.

[78] In his account, the involvement of the wealthy, primarily priestly elite contributed to Rome's perception of the uprising as a full-scale rebellion and fueled internal divisions within the short-lived independent rebel state.

[98] Agrippa warned that refusing to pay tribute and dismantling the porticoes connecting the Antonia Fortress to the Temple constituted rebellion, urging their restoration and payment of taxes to avoid further accusations.

[103][104][e] Around this time, a faction of Sicarii, led by Menahem ben Judah, a descendant of Judas of Galilee,[105][102] carried out a surprise assault on the desert fortress of Masada, near the southwestern shore of the Dead Sea.

[110] Later, in mid-September,[110] when the besieged Roman soldiers surrendered their weapons in exchange for safe passage, the rebels massacred them, sparing only their commander Metilius, who pledged to convert to Judaism and undergo circumcision.

[145] E. Mary Smallwood proposed that Gallus may have been concerned about the impending winter, the lack of proper siege equipment, the risk of rebel ambushes in the hills, and the possible insincerity of the moderates' offer to open the gates.

[163] After the Temple meeting,[166] Jerusalem's priestly leadership[167] began minting coins, an act that symbolized the rejection of Roman authority and foreign currency while asserting the new Jewish state's responsibility for its financial affairs.

[278] Following this, Lucius Annius was sent to Gerasa (likely a textual error for Gezer), where after capturing the city, he executed many young men, enslaved women and children, plundered and burned the homes, and destroyed surrounding villages, slaughtering those who could not escape.

[373][374] According to Josephus, Titus spared only three towers of Herod's palace and a section of the city's western wall to protect the Roman garrison stationed there, while the rest of Jerusalem was systematically razed to the ground.

[380] John of Gischala surrendered and was sentenced to life imprisonment,[374] while Simon Bar Giora, emerging at the site of the destroyed temple dressed in white and purple, was captured by Terentius Rufus and sent to Titus in Caesarea.

[390][391] The rebels capitulated after Eleazar, a young man from a prominent Jewish family who had ventured outside the fort, was captured, stripped, and scourged in full view of the defenders in preparation for crucifixion.

[409] Archaeological work at Masada uncovered eleven ostraca (one of which contained the name of Ben Yair, possibly used to determine the order of suicide), twenty-five skeletons of the defenders, and religious structures, including ritual baths and a synagogue.

The aristocratic oligarchy, consisting of the families of the High Priesthood and their affiliates, who wielded significant political, social, and economic influence and amassed great wealth, suffered a total collapse.

[400] Vespasian further solidified Roman control over the province by granting colony status to Caesarea, the provincial capital, renaming it Colonia Prima Flavia Augusta Caesarensis, and settling many veterans there.

[448] After the revolt, Roman authorities intensified their efforts to quell any potential uprisings in Jewish diaspora communities, targeting individuals deemed as troublemakers in Egypt and Cyrenaica,[434] which had absorbed thousands of refugees and insurgents from Judaea.

[467] Glen Bowersock writes that revolt and the destruction of Jerusalem brought Jews to the Arabian Peninsula, leading to the establishment of settlements in southern Yemen, along the coast of Ḥaḍramawt, and most notably in the northwestern Ḥijāz, particularly in Yathrib (later Medina), where they became prominent representatives of monotheism in pre-Islamic Arabia.

[475] The Sadducees, whose authority was closely tied to the Temple, dissolved as a distinct group due to the loss of their power base, their role in the revolt, the confiscation of land, and the collapse of Jewish self-governance.

However, he believed that the covenant between God and Israel remained valid, with restoration dependent on Jewish repentance, a view akin to that of Jeremiah and the biblical authors of the Deuteronomic history regarding the destruction of the First Temple.

[498] In the aftermath of the revolt, Jewish apocalyptic literature saw a revival,[499] with works like the Apocalypse of Baruch and Fourth Esdras mourning the destruction of the Temple, offering explanations for it, and expressing hopes for Jerusalem's restoration.

It foretells that "a leader of Rome will come to Syria, who will burn the Temple of Jerusalem with fire, slaughter many men, and destroy the great land of the Jews with its broad roads"[511] and prophesies the return of Nero—widely believed at the time to have fled to the East, rather than committed suicide—as an instrument of divine wrath against the Romans in general and the Flavians more specifically.

[482] While the details remain difficult to verify, and since the existing sources differ regarding his conversation with Vespasian and his requests from him, various explanations have been offered for how ben Zakkai arrived in Yavneh and established it as the new center of Jewish spirituality.

In 115 CE, large-scale Jewish uprisings, known as the Diaspora Revolt, erupted almost simultaneously across several eastern provinces, including Cyprus, Egypt, Libya, and Mesopotamia, with limited activity in Judaea.

[454][383] Moving scaffolds, some three or four stories high, displayed golden frames, ivory craftsmanship, and gold tapestries, illustrating scenes of the war such as ruined cities, destroyed fortresses, defeated enemies, and captured generals.

[567] The obverse featured portraits of either Vespasian or, more commonly, Titus,[567] while the reverse depicted symbolic imagery: a mourning woman, representing the Jewish people, seated beneath a date palm, emblematic of the province of Judaea.

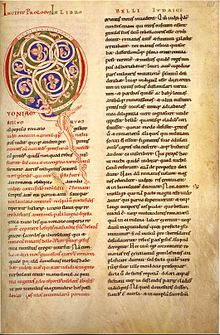

[356][594] The work primarily draws on Josephus' firsthand observations as a participant and eyewitness during the first years of the revolt, supplemented by accounts from Jewish deserters, and relies on memoirs and military commentaries for the later events.

[ac] At the same time, despite the subjective and partial nature of the work, Josephus' experience as a participant and eyewitness, as well as his knowledge of both Jewish and Roman worlds, renders his account an invaluable historical source.

[614][616][617] Documentary evidence, such as texts from Wadi Murabba'at, includes dating formulas and phrases resembling those found on revolt coinage, shedding light on the legal and everyday aspects of life during the uprising.