Land reform in Mexico

In the 19th century, Mexican elites consolidated large landed estates (haciendas) in many parts of the country while small holders, many of whom were mixed-race mestizos, engaged with the commercial economy.

After the War of Independence, Mexican liberals sought to modernize the economy, promoting commercial agriculture through the dissolution of common lands, most of which were then property of the Catholic Church, and indigenous communities.

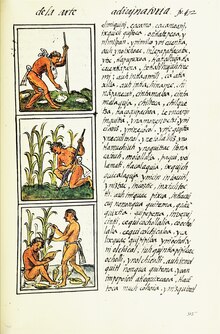

[8] The rich lands of central and southern Mexico were the home to dense, hierarchically organized, settled populations that produced agricultural surpluses, allowing the development of sectors that did not directly cultivate the soil.

[14] Local-level records in Nahuatl from the 16th century show that individuals and community members kept track of these categories, including purchased land, and often the previous owners of particular plots.

These grants did not include land, which in the immediate post-conquest era was not as important as the tribute and labor service that Indians could provide as a continuation from the prehispanic period.

At the same time, decreases in indigenous populations and Spanish migration to Mexico created a demand for foodstuffs familiar to them, such as wheat rather than maize, European fruits, and animals such as cattle, sheep, and goats for meat and hides or wool.

[citation needed] The crown attempted to cluster remaining indigenous populations, relocating them in new communities in a process known as congregacion or reducción, with mixed results.

[36] The Spanish crown granted mercedes to favored Spaniards, and in the case of the conqueror Hernán Cortés, created the entailment of the Marquesado del Valle de Oaxaca.

[40] Jovellanos’s writings influenced (without attribution) a prominent cleric in independence-era New Spain, Manuel Abad y Queipo, who compiled copious data about the agrarian situation in the late 18th century and who conveyed it to Alexander von Humboldt.

At the turn of the 19th century the Spanish crown attempted to tap what it thought was the vast wealth of the church by demanding that those holding mortgages pay the principal as a lump sum immediately rather than incrementally over the long term.

From the point of view of the landed elite, the crown's demands were "a savage capital levy" which would "destroy the country’s credit system and drain the economy of its currency.

"[48] The outbreak of the insurgency in September 1810 led by secular cleric Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla was joined by Indians and castas in huge numbers in the commercial agricultural region of the Bajío.

It has been argued that the perception that the ruling elites were divided in 1810, embodied in the authority figure of a Spanish priest denouncing bad government, gave the masses in the Bajío the idea that violent rebellion might succeed in changing their circumstances for the better.

More successful in demonstrating that agrarian violence could achieve gains for peasants was the guerrilla warfare that continued after the failure of the Hidalgo revolt and the execution of its leaders.

Rather than a massed group of men attempting to achieve a quick and decisive victory pitted against the small but effective royal army, guerrilla warfare waged over time undermined the security and stability of the colonial regime.

[55] The survival of guerrilla movements was dependent on support from surrounding villages and the continuing violence undermined the local economies, however, they did not formulate an ideology of agrarian reform.

[60] During the presidency of liberal general Porfirio Díaz, the regime embarked on a sweeping project of modernization, inviting foreign entrepreneurs to invest in Mexican mining, agriculture, industry, and infrastructure.

[63] U.S. investors acquired land along the Mexico's northern border, especially Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Tamaulipas, but also on both coasts as well as the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

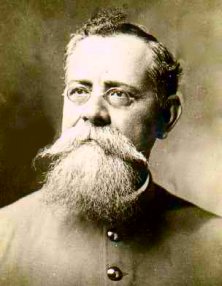

"[71] A key influence on agrarian land reform in revolutionary Mexico was of Andrés Molina Enríquez, who is considered the intellectual father of Article 27 of the 1917 Constitution.

[73] In his observations, it was not the large estates or the subsistence peasants that produced the largest amount of maize in the region, but rather the rancheros; he considered the hacendado group "inherently evil".

[75] In The Great National Problems, Molina Enríquez concluded that the Porfirio Díaz regime had promoted the growth of large haciendas although they were not as productive as small holdings.

Citing his nearly decade long tenure as a notary, his claims were well-founded that haciendas were vastly under-assessed for tax purposes and that small holders were disadvantaged against the wealth and political connections of large estate owners.

[78] The Mexican Revolution reversed the Porfirian trend towards land concentration and set in motion a long process of agrarian mobilization that the post-revolutionary state sought to control and prevent further major peasant uprisings.

The radical and egalitarian sentiments produced by the revolution had made landlord rule of the old kind impossible, but the Mexican state moved to stifle peasant mobilization and the recreation of indigenous community power.

The economic Panic of 1907 in the U.S. had an impact on the border state of Chihuahua, where newly unemployed miners, embittered former military colonists, and small holders joined to support Francisco I. Madero's movement to oust Díaz.

Northerners sought more than a small plot of land for subsistence agriculture, but rather a parcel large enough to be designated a rancho on which they could cultivate and/or ranch cattle independently.

[82] One of Carranza's principal aides, Luis Cabrera, the law partner of Andrés Molina Enríquez, drafted the Agrarian Decree of January 6, 1915, promising to provide land for those in need of it.

[82] The driving idea behind the law was to blunt the appeal of Zapatismo and to give peasants access to land to supplement income during periods when they were not employed as day laborers on large haciendas and fought against the Constitutionalists.

"[83] With the defeat of Victoriano Huerta, the Constitutionalist faction split, with Villa and Zapata, who advocated more radical agrarian policies, opposing Carranza and Obregón.

Since the Zapatistas had supported his bid for power, he placated them by ending attempts to recover seized land and return them to big sugar estate owners.