Lead dioxide

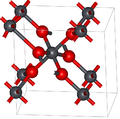

Lead dioxide has two major polymorphs, alpha and beta, which occur naturally as rare minerals scrutinyite and plattnerite, respectively.

[4] Lead dioxide decomposes upon heating in air as follows: The stoichiometry of the end product can be controlled by changing the temperature – for example, in the above reaction, the first step occurs at 290 °C, second at 350 °C, third at 375 °C and fourth at 600 °C.

It dissolves in strong bases to form the hydroxyplumbate ion, [Pb(OH)6]2−:[2] It also reacts with basic oxides in the melt, yielding orthoplumbates M4[PbO4].

Because of the instability of its Pb4+ cation, lead dioxide reacts with hot acids, converting to the more stable Pb2+ state and liberating oxygen:[6] However these reactions are slow.

Like metals, lead dioxide has a characteristic electrode potential, and in electrolytes it can be polarized both anodically and cathodically.

Therefore, an alternative method is to use harder substrates, such as titanium, niobium, tantalum or graphite and deposit PbO2 onto them from lead(II) nitrate in static or flowing nitric acid.

Lead dioxide anodes are inexpensive and were once used instead of conventional platinum and graphite electrodes for regenerating potassium dichromate.

Chronic contact with the skin can potentially cause lead poisoning through absorption, or redness and irritation in the short term.

[15][better source needed] Lead dioxide is poisonous to aquatic life, but because of its insolubility it usually settles out of water.