Middle Ages

Population decline, counterurbanisation, the collapse of centralised authority, invasions, and mass migrations of tribes, which had begun in late antiquity, continued into the Early Middle Ages.

The theology of Thomas Aquinas, the paintings of Giotto, the poetry of Dante and Chaucer, the travels of Marco Polo, and the Gothic architecture of cathedrals such as Chartres are among the outstanding achievements toward the end of this period and into the Late Middle Ages.

The Late Middle Ages was marked by difficulties and calamities, including famine, plague, and war, which significantly diminished the population of Europe; between 1347 and 1350, the Black Death killed about a third of Europeans.

[10] Leonardo Bruni was the first historian to use tripartite periodisation in his History of the Florentine People (1442), with a middle period "between the fall of the Roman Empire and the revival of city life sometime in late eleventh and twelfth centuries".

[21] Economic issues, including inflation, and external pressure on the frontiers combined to create the Crisis of the Third Century, with emperors coming to the throne only to be rapidly replaced by new usurpers.

[28] For much of the 4th century, Roman society stabilised in a new form that differed from the earlier classical period, with a widening gulf between the rich and poor, and a decline in the vitality of the smaller towns.

The Franks, Alemanni, and the Burgundians all ended up in northern Gaul while the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes settled in Britain,[37] and the Vandals went on to cross the strait of Gibraltar after which they conquered the province of Africa.

In the 560s, the Avars began to expand from their base on the north bank of the Danube; by the end of the 6th century, they were the dominant power in Central Europe and routinely able to force the Eastern emperors to pay tribute.

[94] Monks and monasteries had a profound effect on the religious and political life of the Early Middle Ages, in various cases acting as land trusts for powerful families, centres of propaganda and royal support in newly conquered regions, and bases for missions and proselytisation.

Pippin's takeover was reinforced with propaganda that portrayed the Merovingians as inept or cruel rulers, exalted the accomplishments of Charles Martel, and circulated stories of the family's great piety.

[122] The break-up of the Abbasid dynasty meant that the Islamic world fragmented into smaller political states, some of which began expanding into Italy and Sicily, as well as over the Pyrenees into the southern parts of the Frankish kingdoms.

In Anglo-Saxon England, King Alfred the Great (r. 871–899) came to an agreement with the Viking invaders in the late 9th century, resulting in Danish settlements in Northumbria, Mercia, and parts of East Anglia.

The estimated population of Europe grew from 35 to 80 million between 1000 and 1347, although the exact causes remain unclear: improved agricultural techniques, the decline of slaveholding, a more clement climate and the lack of invasion have all been suggested.

[188] The papacy, long attached to an ideology of independence from secular kings, first asserted its claim to temporal authority over the entire Christian world; the Papal Monarchy reached its apogee in the early 13th century under the pontificate of Innocent III (pope 1198–1216).

[189] Northern Crusades and the advance of Christian kingdoms and military orders into previously pagan regions in the Baltic and Finnic north-east brought the forced assimilation of numerous native peoples into European culture.

John's financial exactions to pay for his unsuccessful attempts to regain Normandy led in 1215 to Magna Carta, a charter that confirmed the rights and privileges of free men in England.

[203] The French monarchy continued to make gains against the nobility during the late 12th and 13th centuries, bringing more territories within the kingdom under the king's personal rule and centralising the royal administration.

[231] Among the results of the Greek and Islamic influence on this period in European history was the replacement of Roman numerals with the decimal positional number system and the invention of algebra, which allowed more advanced mathematics.

[246] The large portal with coloured sculpture in high relief became a central feature of façades, especially in France, and the capitals of columns were often carved with narrative scenes of imaginative monsters and animals.

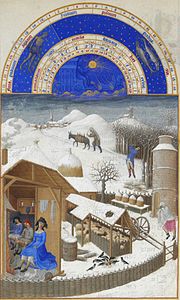

Large illuminated bibles and psalters were the typical forms of luxury manuscripts, and wall-painting flourished in churches, often following a scheme with a Last Judgement on the west wall, a Christ in Majesty at the east end, and narrative biblical scenes down the nave, or in the best surviving example, at Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe, on the barrel-vaulted roof.

[251] From the early 12th century, French builders developed the Gothic style, marked by the use of rib vaults, pointed arches, flying buttresses, and large stained glass windows.

[256] Increasing prosperity during the 12th century resulted in greater production of secular art; many carved ivory objects such as gaming-pieces, combs, and small religious figures have survived.

[278][AD] Strong, royalty-based nation states rose throughout Europe in the Late Middle Ages, particularly in England, France, and the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula: Aragon, Castile, and Portugal.

[244] In modern-day Germany, the Holy Roman Empire continued to rule, but the elective nature of the imperial crown meant there was no enduring dynasty around which a strong state could form.

John Wycliffe (d. 1384), an English theologian, was condemned as a heretic in 1415 for teaching that the laity should have access to the text of the Bible as well as for holding views on the Eucharist that were contrary to Church doctrine.

By the late 15th century, the Church had begun to lend credence to populist fears of witchcraft with its condemnation of witches in 1484 and the publication in 1486 of the Malleus Maleficarum, the most popular handbook for witch-hunters.

[312] The publication of vernacular literature increased, with Dante (d. 1321), Petrarch (d. 1374) and Giovanni Boccaccio (d. 1375) in 14th-century Italy, Geoffrey Chaucer (d. 1400) and William Langland (d. c. 1386) in England, and François Villon (d. 1464) and Christine de Pizan (d. c. 1430) in France.

In the 15th century, the mercantile classes of Italy and Flanders became important patrons, commissioning small portraits of themselves in oils as well as a growing range of luxury items such as jewellery, ivory caskets, cassone chests, and maiolica pottery.

Science historian Edward Grant writes, "If revolutionary rational thoughts were expressed [in the 18th century], they were only made possible because of the long medieval tradition that established the use of reason as one of the most important of human activities".

[334] Also, contrary to common belief, David Lindberg writes, "the late medieval scholar rarely experienced the coercive power of the Church and would have regarded himself as free (particularly in the natural sciences) to follow reason and observation wherever they led".