Military history of Italy

Like many ancient societies, the Italics and the Etruscans conducted campaigns during summer months, raiding neighboring areas, attempting to gain territory and combating piracy/banditry as a means of acquiring valuable resources such as land, prestige and goods.

Non-Celtic people like Ligures in the western part, and Adriatic Veneti in the eastern, also existed and were the majority of population of Cisalpine Gaul, although they were very influenced by Celts in their culture, and warfare was no exception.

During the 5th century BC the cities of Padanian Etruria fell due to the expansion of the Celts, and the latter also arrived on the Adriatic coast of central Italy, in the current area of northern Marche, where some weapons were discovered Celtic then also adopted by the Romans.

[14] Until the late Republican period, the typical legionary was a property-owning citizen farmer from a rural area (an adsiduus) who served for particular (often annual) campaigns,[15] and who supplied his own equipment and, in the case of equites, his own mount.

During the later Republic, members of the Roman Senatorial elite, as part of the normal sequence of elected public offices known as the cursus honorum, would have served first as quaestor (often posted as deputies to field commanders), then as praetor.

The quinquereme was the main warship on both sides of the Punic Wars and remained the mainstay of Roman naval forces until replaced by the time of Caesar Augustus by lighter and more maneuverable vessels.

[28] Throughout the Middle Ages, from the collapse of a central Roman government in the late 5th century to the Italian Wars of the Renaissance, Italy was constantly divided between opposing factions fighting for control.

For the next two centuries, the Byzantine power in the peninsula was reduced by the Lombard kings, the greatest of which was Liutprand, until it consisted of little more than the tips of the Italian toe and heel, Rome and its environs being practically independent under the popes and the Neapolitan coast under its dukes.

The victory of the Guelph party meant the end of Imperial overlordship over northern Italy, and the formation of city-states such as Milan, Florence, Pisa, Siena, Genoa, Ferrara, Mantua, Verona, and Venice.

The county of Savoy expanded its territory into the peninsula in the late Middle Ages, while Florence developed into a highly organized commercial and financial city-state, becoming for many centuries the European capital of silk, wool, banking and jewelry.

While Venice was turning to the seas, supporting, and acquiring large loot from, the 1204 Fourth Crusade's sack of Constantinople, the other city-states were struggling for control of mainland, Florence being the rising power of the time.

In 1508, Pope Julius II formed the League of Cambrai, in which France, the Papacy, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire agreed to attack the Republic of Venice and partition her mainland territories.

[31] The French were driven from Italy in late 1512, despite their victory at the Battle of Ravenna earlier that year, leaving Milan in the hands of Maximilian Sforza and his Swiss mercenaries; but the Holy League fell apart over the subject of dividing the spoils, and in 1513 Venice allied with France, agreeing to partition Lombardy between them.

By the end of the wars in 1559, Habsburg Spain had been left in control of about half of Italy (the southern kingdoms of Naples, Sardinia and Sicily, as well as the Duchy of Milan in the north)), to the detriment of France.

[42] During the whole century there was a general tendency to enlarge the army, in 1774 the total number of Savoyan troops reached 100.000 units and it was in that occasion that the regulation concerning the duration of the permanent military service was introduced.

[49] The Victor Emmanuel II Monument holds the Tomb of the Italian Unknown Soldier with an eternal flame, built under the statue of goddess Roma after World War I following an idea of General Giulio Douhet.

[64] In spite of its official status as member of the Triple Alliance together with Germany and Austria-Hungary, in the years before the outbreak of the conflict the Italian government had enhanced its diplomatic efforts towards United Kingdom and France.

A few days after the outbreak of the conflict, on 3 August 1914, the government, led by the conservative Antonio Salandra, declared that Italy would not commit its troops, maintaining that the Triple Alliance had only a defensive stance, whereas Austria-Hungary had been the aggressor.

In reality, both Salandra and the minister of Foreign Affairs, Sidney Sonnino, started diplomatic activities to probe which side was ready to grant the best reward for Italy's entrance in the war.

By the Pact, in case of victory Italy was to be given Trentino and the South Tyrol up to the Brenner Pass, the entire Austrian Littoral (with Trieste, Gorizia-Gradisca and Istria, but without Fiume), parts of western Carniola (Idrija and Ilirska Bistrica) and north-western Dalmatia with Zadar and most of the islands, but without Split.

However, this advantage was never fully utilized because Italian military commander Luigi Cadorna insisted on a dangerous frontal assault against Austria-Hungary in an attempt to occupy the Slovenian plateau and Ljubljana.

[102] During his time in Fiume in September 1919, the Italian poet, editor, and art theorist, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the founder of the Futurist movement, praised the leaders of the impresa as "advance-guard deserters" (disertori in avanti).

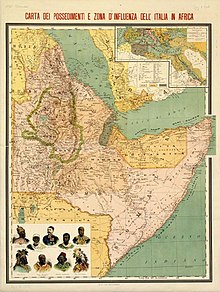

General Emilio de Bono put on record that preparations for the invasion of Ethiopia (Abyssinia) had been going on since 1932 as roads were being built from Italian Somaliland into Ethiopian territory, though Mussolini constantly claimed that he was not a "collector of deserts" and would never think of invading.

[104] On 31 March 1936, a desperate final counter-attack by Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia, was carried out, though word of the attack had already gotten to the Italians, giving them victory in the Battle of Maychew again through the use of chemical weapons.

"[138] Some historians believe that Italian leader Benito Mussolini was induced to enter the war against the Allies by secret negotiations with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, with whom he had an active mail correspondence between September 1939 and June 1940.

[139] The journalist Luciano Garibaldi wrote that "in those letters (which disappeared at Lake Como in 1945) Churchill may have extorted Mussolini to enter the war to mitigate Hitler's demands and dissuade him from continuing hostilities against Great Britain as France was inexorably moving toward defeat.

In 1940, the Italian Armistice Commission (Commissione Italiana d'Armistizio con la Francia, CIAF) produced two detailed plans concerning the future of the occupied French territories.

[142] However, British troops took the initiative in Africa while Italy was still having trouble pacifying Ethiopia and General Wavell kept up a constantly moving front of raids on Italian positions that proved to be successful.

After large propaganda campaigns and even the sinking of a Greek light cruiser, Mussolini then handed an ultimatum to Ioannis Metaxas, Prime Minister of Greece, which would initiate the Greco-Italian War.

The Italian Navy also contributed a naval task force that included the aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi, a frigate (Maestrale) and a submarine (Sauro class), that operated with other NATO ships in the Adriatic sea.

Italian German annexed by Bulgaria .

The Italian zone was taken over by the Germans in September 1943.