Nuclear receptor

In the field of molecular biology, nuclear receptors are a class of proteins responsible for sensing steroids, thyroid hormones, vitamins, and certain other molecules.

These intracellular receptors work with other proteins to regulate the expression of specific genes, thereby controlling the development, homeostasis, and metabolism of the organism.

[6][7] Nuclear receptors are specific to metazoans (animals) and are not found in protists, algae, fungi, or plants.

[8] Amongst the early-branching animal lineages with sequenced genomes, two have been reported from the sponge Amphimedon queenslandica, two from the comb jelly Mnemiopsis leidyi[9] four from the placozoan Trichoplax adhaerens and 17 from the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis.

Nuclear receptors (NRs) may be classified into two broad classes according to their mechanism of action and subcellular distribution in the absence of ligand.

[4] Accordingly, nuclear receptors may be subdivided into the following four mechanistic classes:[4][5] Ligand binding to type I nuclear receptors in the cytosol results in the dissociation of heat shock proteins, homo-dimerization, translocation (i.e., active transport) from the cytoplasm into the cell nucleus, and binding to specific sequences of DNA known as hormone response elements (HREs).

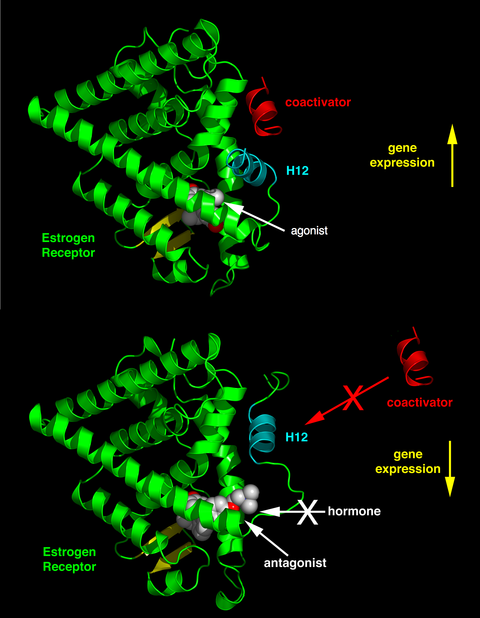

Nuclear receptors may bind specifically to a number of coregulator proteins, and thereby influence cellular mechanisms of signal transduction both directly, as well as indirectly.

[38] The activity of endogenous ligands (such as the hormones estradiol and testosterone) when bound to their cognate nuclear receptors is normally to upregulate gene expression.

The agonistic effects of endogenous hormones can also be mimicked by certain synthetic ligands, for example, the glucocorticoid receptor anti-inflammatory drug dexamethasone.

Agonist ligands work by inducing a conformation of the receptor which favors coactivator binding (see upper half of the figure to the right).

Finally, some nuclear receptors promote a low level of gene transcription in the absence of agonists (also referred to as basal or constitutive activity).

Synthetic ligands which reduce this basal level of activity in nuclear receptors are known as inverse agonists.

In tissues where the concentration of coactivator proteins is higher than corepressors, the equilibrium is shifted in the agonist direction.

Furthermore, these membrane associated receptors function through alternative signal transduction mechanisms not involving gene regulation.

A molecular mechanism for non-genomic signaling through the nuclear thyroid hormone receptor TRβ involves the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K).

[46] This signaling can be blocked by a single tyrosine to phenylalanine substitution in TRβ without disrupting direct gene regulation.

[47] When mice were created with this single, conservative amino acid substitution in TRβ,[47] synaptic maturation and plasticity in the hippocampus was impaired almost as effectively as completely blocking thyroid hormone synthesis.

Thus, phosphotyrosine-dependent association of TRβ with PI3K provides a potential mechanism for integrating regulation of development and metabolism by thyroid hormone and receptor tyrosine kinases.

[6][7] The list also includes selected family members that lack human orthologs (NRNC symbol highlighted in yellow).

[50] The placement of C. elegans nhr-1 (Q21878) is disputed: although most sources place it as NR1K1,[50] manual annotation at WormBase considers it a member of NR2A.

This debate began more than twenty-five years ago when the first ligands were identified as mammalian steroid and thyroid hormones.

This hypothesis suggests that the ancestral receptor may act as a lipid sensor with an ability to bind, albeit rather weakly, several different hydrophobic molecules such as, retinoids, steroids, hemes, and fatty acids.

Top – Schematic 1D amino acid sequence of a nuclear receptor.

Bottom – 3D structures of the DBD (bound to DNA) and LBD (bound to hormone) regions of the nuclear receptor. The structures shown are of the estrogen receptor . Experimental structures of N-terminal domain (A/B), hinge region (D), and C-terminal domain (F) have not been determined therefore are represented by red, purple, and orange dashed lines, respectively.