Marine biogeochemical cycles

Energy flows directionally through ecosystems, entering as sunlight (or inorganic molecules for chemoautotrophs) and leaving as heat during the many transfers between trophic levels.

The six most common elements associated with organic molecules—carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur—take a variety of chemical forms and may exist for long periods in the atmosphere, on land, in water, or beneath the Earth's surface.

Geologic processes, such as weathering, erosion, water drainage, and the subduction of the continental plates, all play a role in this recycling of materials.

Because geology and chemistry have major roles in the study of this process, the recycling of inorganic matter between living organisms and their environment is called a biogeochemical cycle.

[3][4] This ability allows it to be the "solvent of life"[5] Water is also the only common substance that exists as solid, liquid, and gas in normal terrestrial conditions.

[9] Cultural eutrophication of lakes is primarily due to phosphorus, applied in excess to agricultural fields in fertilizers, and then transported overland and down rivers.

[11] Ocean salinity is derived mainly from the weathering of rocks and the transport of dissolved salts from the land, with lesser contributions from hydrothermal vents in the seafloor.

Warm surface waters are depleted of nutrients and carbon dioxide, but they are enriched again as they travel through the conveyor belt as deep or bottom layers.

[76] The biological pump can be divided into three distinct phases,[77] the first of which is the production of fixed carbon by planktonic phototrophs in the euphotic (sunlit) surface region of the ocean.

Once this carbon is fixed into soft or hard tissue, the organisms either stay in the euphotic zone to be recycled as part of the regenerative nutrient cycle or once they die, continue to the second phase of the biological pump and begin to sink to the ocean floor.

The fixed carbon that is either decomposed by bacteria on the way down or once on the sea floor then enters the final phase of the pump and is remineralized to be used again in primary production.

Ammonium is thought to be the preferred source of fixed nitrogen for phytoplankton because its assimilation does not involve a redox reaction and therefore requires little energy.

Phosphorus does enter the atmosphere in very small amounts when the dust is dissolved in rainwater and seaspray but remains mostly on land and in rock and soil minerals.

Recent research suggests that the predominant pollutant responsible for algal blooms in saltwater estuaries and coastal marine habitats is nitrogen.

The process is regulated by the pathways available in marine food webs, which ultimately decompose organic matter back into inorganic nutrients.

From a practical point, it does not make sense to assess a terrestrial ecosystem by considering the full column of air above it as well as the great depths of Earth below it.

While an ecosystem often has no clear boundary, as a working model it is practical to consider the functional community where the bulk of matter and energy transfer occurs.

CO2 is nearly opposite to oxygen in many chemical and biological processes; it is used up by plankton during photosynthesis and replenished during respiration as well as during the oxidation of organic matter.

The benthic marine sulfur cycle is therefore sensitive to anthropogenic influence, such as ocean warming and increased nutrient loading of coastal seas.

This stimulates photosynthetic productivity and results in enhanced export of organic matter to the seafloor, often combined with low oxygen concentration in the bottom water (Rabalais et al., 2014; Breitburg et al., 2018).

The biogeochemical zonation is thereby compressed toward the sediment surface, and the balance of organic matter mineralization is shifted from oxic and suboxic processes toward sulfate reduction and methanogenesis (Middelburg and Levin, 2009).

[95] In modern oceans, Hydrogenovibrio crunogenus, Halothiobacillus, and Beggiatoa are primary sulfur oxidizing bacteria,[96][97] and form chemosynthetic symbioses with animal hosts.

[114] Dead organisms sink to the bottom of the ocean, depositing layers of shell which over time cement to form limestone.

[118] Tracking calcium isotopes enables the prediction of environmental changes, with many sources suggesting increasing temperatures in both the atmosphere and marine environment.

Increasing carbon dioxide levels and decreasing ocean pH will alter calcium solubility, preventing corals and shelled organisms from developing their calcium-based exoskeletons, thus making them vulnerable or unable to survive.

Inputs of silicon to the ocean from above arrive via rivers and aeolian dust, while those from below include seafloor sediment recycling, weathering, and hydrothermal activity.

Understanding the interactions between organisms and their abiotic environment, and the resulting coupled evolution of the biosphere and geosphere is a central theme of research in biogeology.

Seawater percolates into oceanic crust and hydrates igneous rocks such as olivine and pyroxene, transforming them into hydrous minerals such as serpentines, talc and brucite.

Despite this, changes in the global sea level over the past 3–4 billion years have only been a few hundred metres, much smaller than the average ocean depth of 4 kilometres.

The resulting high temperature and pressure caused the organic matter to chemically alter, first into a waxy material known as kerogen, which is found in oil shales, and then with more heat into liquid and gaseous hydrocarbons in a process known as catagenesis.

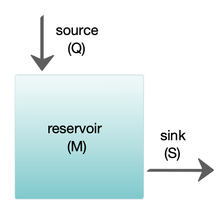

example of a more complex model with many interacting boxes

carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles

DOM: dissolved organic material POM: particulate organic material

interact with other bacteria to acquire iron from dust

b. Trichodesmium can establish massive blooms in nutrient poor ocean regions with high dust deposition, partly due to their unique ability to capture dust, center it, and subsequently dissolve it.

c. Proposed dust-bound Fe acquisition pathway: Bacteria residing within the colonies produce siderophores (C-I) that react with the dust particles in the colony core and generate dissolved Fe (C-II). This dissolved Fe, complexed by siderophores, is then acquired by both Trichodesmium and its resident bacteria (C-III), resulting in a mutual benefit to both partners of the consortium . [ 110 ]

Fluxes in T mol Si y −1 = 28 million tonnes of silicon per year