Late Pleistocene extinctions

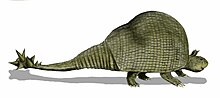

The Late Pleistocene to the beginning of the Holocene saw the extinction of the majority of the world's megafauna (typically defined as animal species having body masses over 44 kilograms (97 lb)),[1] which resulted in a collapse in faunal density and diversity across the globe.

For instance, ground sloths survived on the Antilles long after North and South American ground sloths were extinct, woolly mammoths died out on remote Wrangel Island 6,000 years after their extinction on the mainland, and Steller's sea cows persisted off the isolated and uninhabited Commander Islands for thousands of years after they had vanished from the continental shores of the north Pacific.

[15] The original debates as to whether human arrival times or climate change constituted the primary cause of megafaunal extinctions necessarily were based on paleontological evidence coupled with geological dating techniques.

[2] Extinctions in North America were concentrated at the end of the Late Pleistocene, around 13,800–11,400 years Before Present, which were coincident with the onset of the Younger Dryas cooling period, as well as the emergence of the hunter-gatherer Clovis culture.

More difficult to explain in the context of overkill is the survival of bison, since these animals first appeared in North America less than 240,000 years ago and so were geographically removed from human predators for a sizeable period of time.

The chief criticism of the "prehistoric overkill hypothesis" has been that the human population at the time was too small and/or not sufficiently widespread geographically to have been capable of such ecologically significant impacts.

Some form of a combination of both factors could be plausible, and overkill would be a lot easier to achieve large-scale extinction with an already stressed population due to climate change.

[79] The extinctions are coincident with the end of the Antarctic Cold Reversal (a cooling period earlier and less severe than the Northern Hemisphere Younger Dryas) and the emergence of Fishtail projectile points, which became widespread across South America.

[113] There is little evidence of human interaction with extinct Australian megafauna, with one notable exception being the burning of Genyornis (a type of giant dromornithid bird related to ducks) eggshells.

[118]The megafaunal extinctions were already recognized as a distinct phenomenon by some scientists in the 19th century:[127][128] It is impossible to reflect without the deepest astonishment, on the changed state of [South America].

Formerly it must have swarmed with great monsters, like the southern parts of Africa, but now we find only the tapir, guanaco, armadillo, capybara; mere pigmies compared to antecedents races...

We cannot but believe that there must have been some physical cause for this great change; and it must have been a cause capable of acting almost simultaneously over large portions of the earth's surface, and one which, as far as the Tertiary period at least is concerned, was of an exceptional character.Several decades later in his 1911 book The World of Life (published 2 years before his death), Wallace revisited the issue of the Pleistocene megafauna extinctions, concluding that the extinctons were at least in part the result of human agency in combination with other factors.

In addition, large mammal species like the giant kangaroo Protemnodon appear to have succumbed sooner on the Australian mainland than on Tasmania, which was colonised by humans a few thousand years later.

[139][140] A study published in 2015 supported the hypothesis further by running several thousand scenarios that correlated the time windows in which each species is known to have become extinct with the arrival of humans on different continents or islands.

Extinction through human hunting has been supported by archaeological finds of mammoths with projectile points embedded in their skeletons, by observations of modern naive animals allowing hunters to approach easily[147][148][149] and by computer models by Mosimann and Martin,[150] and Whittington and Dyke,[151] and most recently by Alroy.

[152]In 2024 a paper was published in Science Advances that added additional support to the overkill hypothesis in North America when the skull of an 18 month old child, dated to 12,800 years ago, was analyzed for chemical signatures attributable to both maternal milk and solid food.

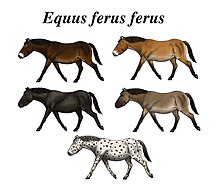

[155][156][157] There is no archeological evidence that in North America megafauna other than mammoths, mastodons, gomphotheres and bison were hunted, despite the fact that, for example, camels and horses are very frequently reported in fossil history.

Any vegetational changes that did occur failed to cause almost any extinctions of small vertebrates, and they are more narrowly distributed on average, which detractors cite as evidence against the hypothesis.

According to this hypothesis, a temperature increase sufficient to melt the Wisconsin ice sheet could have placed enough thermal stress on cold-adapted mammals to cause them to die.

[171] Evidence in Southeast Asia, in contrast to Europe, Australia, and the Americas, suggests that climate change and an increasing sea level were significant factors in the extinction of several herbivorous species.

Alterations in vegetation growth and new access routes for early humans and mammals to previously isolated, localized ecosystems were detrimental to select groups of fauna.

[188] In the North American Great Lakes region, the population declines of mastodons and mammoths have been found to correlate with climatic fluctuations during the Younger Dryas rather than human activity.

This is the opposite of what one would expect if they were experiencing stresses from deteriorating environmental conditions, but is consistent with a reduction in intraspecific competition that would result from a population being reduced by human hunting.

[210] However, a broader variation of the overkill hypothesis may predict this, because changes in vegetation wrought by either Second Order Predation (see below)[166][211] or anthropogenic fire preferentially selects against browse species.

[citation needed] The hyperdisease hypothesis, as advanced by Ross D. E. MacFee and Preston A. Marx, attributes the extinction of large mammals during the late Pleistocene to indirect effects of the newly arrived aboriginal humans.

[215] The hyperdisease hypothesis proposes that humans or animals traveling with them (e.g., chickens or domestic dogs) introduced one or more highly virulent diseases into vulnerable populations of native mammals, eventually causing extinctions.

Yet while remaining sufficiently selective to afflict only individual species within genera it must be capable of fatally infecting across such clades as birds, marsupials, placentals, testudines, and crocodilians.

[citation needed] Numerous species including wolves, mammoths, camelids, and horses had emigrated continually between Asia and North America over the past 100,000 years.

[229] Megafauna play a significant role in the lateral transport of mineral nutrients in an ecosystem, tending to translocate them from areas of high to those of lower abundance.

[246] This hypothesis is supported by rapid megafaunal extinction following recent human colonisation in Australia, New Zealand and Madagascar,[247] in a similar way that any large, adaptable predator moving into a new ecosystem would.