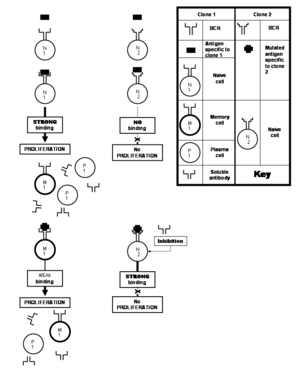

Polyclonal B cell response

It ensures that a single antigen is recognized and attacked through its overlapping parts, called epitopes, by multiple clones of B cell.

The process by which the pathogen is introduced into the body is known as inoculation,[note 1][6] and the organism it affects is known as a biological host.

The collection of various cells, tissues and organs that specializes in protecting the body against infections is known as the immune system.

The major steps involved are:[9] Pathogens synthesize proteins that can serve as "recognizable" antigens; they may express the molecules on their surface or release them into the surroundings (body fluids).

The specificity of binding does not arise out of a rigid lock and key type of interaction, but rather requires both the paratope and the epitope to undergo slight conformational changes in each other's presence.

This mode of recognition is possible only when the peptide is small (about six to eight amino acids long),[1] and is employed by the T cells (T lymphocytes).

[1] Likewise, the antibodies produced by the plasma cells belonging to the same clone would bind to the same conformational epitopes on the pathogen proteins.

[1][17] Since the same receptor could bind to a given motif present on surfaces of widely disparate microorganisms, this mode of recognition is relatively nonspecific, and constitutes an innate immune response.

After recognizing an antigen, an antigen-presenting cell such as the macrophage or B lymphocyte engulfs it completely by a process called phagocytosis.

The engulfed particle, along with some material surrounding it, forms the endocytic vesicle (the phagosome), which fuses with lysosomes.

Within the lysosome, the antigen is broken down into smaller pieces called peptides by proteases (enzymes that degrade larger proteins).

The individual peptides are then complexed with major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC class II) molecules located in the lysosome – this method of "handling" the antigen is known as the exogenous or endocytic pathway of antigen processing in contrast to the endogenous or cytosolic pathway,[17][18][19] which complexes the abnormal proteins produced within the cell (e.g. under the influence of a viral infection or in a tumor cell) with MHC class I molecules.

Some of the newly created paratopes bind more strongly to the same epitope (leading to the selection of the clones possessing them), which is known as affinity maturation.

As the body needs to be able to respond to a large number of potential pathogens, it maintains a pool of B cells with a wide range of specificities.

[17] Consequently, while there is almost always at least one B (naive or memory) cell capable of responding to any given epitope (of all that the immune system can react against), there are very few exact duplicates.

[1] The clones that bind to a particular epitope with greater strength are more likely to be selected for further proliferation in the germinal centers of the follicles in various lymphoid tissues like the lymph nodes.

[23] What makes the analogy even stronger is that the B lymphocytes have to compete with each other for signals that promote their survival in the germinal centers.

Although there are many diverse pathogens, many of which are constantly mutating, it is a surprise that a majority of individuals remain free of infections.

This is achieved by maintaining a pool of immensely large (about 109) clones of B cells, each of which reacts against a specific epitope by recognizing and producing antibodies against it.

[21] Moreover, in a lifetime, an individual usually requires the generation of antibodies against very few antigens in comparison with the number that the body can recognize and respond against.

[24] Many viruses undergo frequent mutations that result in changes in amino acid composition of their important proteins.

This is unfortunate because somatic hypermutation does give rise to clones capable of producing soluble antibodies that would have bound the altered epitope avidly enough to neutralize it.

Hence, wider the range of antibody-specificities, greater the chance that one or the other will react against self-antigens (native molecules of the body).

They are usually not produced in a natural immune response, but only in diseased states like multiple myeloma, or through specialized laboratory techniques.

Monoclonal antibodies find use in various diagnostic modalities (see: western blot and immunofluorescence) and therapies—particularly of cancer and diseases with autoimmune component.

But, since virtually all responses in nature are polyclonal, it makes production of immensely useful monoclonal antibodies less straightforward.

[8] The first evidence of presence of a neutralizing substance in the blood that could counter infections came when Emil von Behring along with Kitasato Shibasaburō in 1890 developed effective serum against diphtheria.

In a few decades to follow, it was shown that the protective serum could neutralize and precipitate toxins, and clump bacteria.

[17][30] It was later shown in 1948 by Astrid Fagraeus in her doctoral thesis that the plasma B cells are specifically involved in antibody production.

[17][30] The clonal selection theory was proved correct when Sir Gustav Nossal showed that each B cell always produces only one antibody.