Ribosome

Ribosomes (/ˈraɪbəzoʊm, -soʊm/) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (messenger RNA translation).

Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA molecules to form polypeptide chains.

In prokaryotes each ribosome is composed of small (30S) and large (50S) components, called subunits, which are bound to each other: The synthesis of proteins from their building blocks takes place in four phases: initiation, elongation, termination, and recycling.

[5] In eukaryotic cells, ribosomes are often associated with the intracellular membranes that make up the rough endoplasmic reticulum.

Ribosomes from bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes (in the three-domain system) resemble each other to a remarkable degree, evidence of a common origin.

In all species, more than one ribosome may move along a single mRNA chain at one time (as a polysome), each "reading" a specific sequence and producing a corresponding protein molecule.

[6][7] Ribosomes were first observed in the mid-1950s by Romanian-American cell biologist George Emil Palade, using an electron microscope, as dense particles or granules.

The present confusion would be eliminated if "ribosome" were adopted to designate ribonucleoprotein particles in sizes ranging from 35 to 100S.Albert Claude, Christian de Duve, and George Emil Palade were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, in 1974, for the discovery of the ribosome.

[11] The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2009 was awarded to Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz and Ada E. Yonath for determining the detailed structure and mechanism of the ribosome.

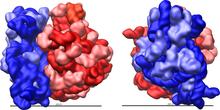

Ribosomes consist of two subunits that fit together and work as one to translate the mRNA into a polypeptide chain during protein synthesis.

[14] Crystallographic work[15] has shown that there are no ribosomal proteins close to the reaction site for polypeptide synthesis.

[19][20] Additional research has demonstrated that the S1 and S21 proteins, in association with the 3′-end of 16S ribosomal RNA, are involved in the initiation of translation.

[17][25][27] During 1977, Czernilofsky published research that used affinity labeling to identify tRNA-binding sites on rat liver ribosomes.

Many pieces of ribosomal RNA in the mitochondria are shortened, and in the case of 5S rRNA, replaced by other structures in animals and fungi.

Much of the RNA is highly organized into various tertiary structural motifs, for example pseudoknots that exhibit coaxial stacking.

The extra RNA in the larger ribosomes is in several long continuous insertions,[38] such that they form loops out of the core structure without disrupting or changing it.

[17] All of the catalytic activity of the ribosome is carried out by the RNA; the proteins reside on the surface and seem to stabilize the structure.

[42] Then, two weeks later, a structure based on cryo-electron microscopy was published,[43] which depicts the ribosome at 11–15 Å resolution in the act of passing a newly synthesized protein strand into the protein-conducting channel.

The ribosome recognizes the start codon by using the Shine-Dalgarno sequence of the mRNA in prokaryotes and Kozak box in eukaryotes.

The ribosome uses tRNA that matches the current codon (triplet) on the mRNA to append an amino acid to the polypeptide chain.

Usually in bacterial cells, several ribosomes are working parallel on a single mRNA, forming what is called a polyribosome or polysome.

For example, one of the possible mechanisms of folding of the deeply knotted proteins relies on the ribosome pushing the chain through the attached loop.

Since the cytosol contains high concentrations of glutathione and is, therefore, a reducing environment, proteins containing disulfide bonds, which are formed from oxidized cysteine residues, cannot be produced within it.

The newly produced polypeptide chains are inserted directly into the ER by the ribosome undertaking vectorial synthesis and are then transported to their destinations, through the secretory pathway.

[66] Studies suggest that ancient ribosomes constructed solely of rRNA could have developed the ability to synthesize peptide bonds.

[81][82] Heterogeneity in ribosome composition was first proposed to be involved in translational control of protein synthesis by Vince Mauro and Gerald Edelman.

Evidence has suggested that specialized ribosomes specific to different cell populations may affect how genes are translated.

In budding yeast, 14/78 ribosomal proteins are non-essential for growth, while in humans this depends on the cell of study.

[86] Other forms of heterogeneity include post-translational modifications to ribosomal proteins such as acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation.

For example, 40S ribosomal units without eS25 in yeast and mammalian cells are unable to recruit the CrPV IGR IRES.