Silicon compounds

Silanes, compounds of silicon and hydrogen, are often used as strong reducing agents, and can be prepared from aluminum–silicon alloys and hydrochloric acid.

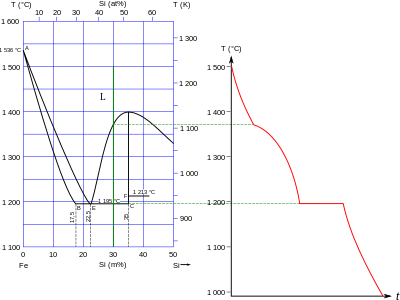

Instead, most form eutectic mixtures, although the heaviest stable ones – mercury, thallium, lead, and bismuth – are completely immiscible with liquid silicon.

For example, the alkali metal silicides (M+)4(Si4−4) contain pyramidal tricoordinate silicon in the Si4−4 anion, isoelectronic with white phosphorus, P4.

Silane itself, as well as trichlorosilane, were first synthesised by Friedrich Wöhler and Heinrich Buff in 1857 by reacting aluminium–silicon alloys with hydrochloric acid, and characterised as SiH4 and SiHCl3 by Charles Friedel and Albert Ladenburg in 1867.

Direct reaction of HX or RX with silicon, possibly with a catalyst such as copper, is also a viable method of producing substituted silanes.

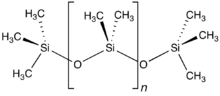

[4] With suitable organic substituents it is possible to produce stable polysilanes: they have surprisingly high electric conductivities, arising from sigma delocalisation of the electrons in the chain.

A suggested explanation for this phenomenon is the compensation for the electron loss of silicon to the more electronegative halogen atoms by pi backbonding from the filled pπ orbitals on the halogen atoms to the empty dπ orbitals on silicon: this is similar to the situation of carbon monoxide in metal carbonyl complexes and explains their stability.

Twelve different crystal modifications of silica are known, the most common being α-quartz, a major constituent of many rocks such as granite and sandstone.

Some poorly crystalline forms of quartz are also known, such as chalcedony, chrysoprase, carnelian, agate, onyx, jasper, heliotrope, and flint.

In the thermodynamically stable room-temperature form, α-quartz, these tetrahedra are linked in intertwined helical chains with two different Si–O distances (159.7 and 161.7 pm) with a Si–O–Si angle of 144°.

Further heating to 867 °C results in another reversible phase transition to β-tridymite, in which some Si–O bonds are broken to allow for the arrangement of the SiO tetrahedra into a more open and less dense hexagonal structure.

In vitreous silica, the SiO tetrahedra remain corner-connected, but the symmetry and periodicity of the crystalline forms are lost.

Silica nevertheless reacts with many metal and metalloid oxides to form a wide variety of compounds important in the glass and ceramic industries above all, but also have many other uses: for example, sodium silicate is often used in detergents due to its buffering, saponifying, and emulsifying properties.

[14] Adding water to silica drops its melting point by around 800 °C due to the breaking of the structure by replacing Si–O–Si linkages with terminating Si–OH groups.

[14] About 95% of the Earth's crustal rocks are made of silica or silicate and aluminosilicate minerals, as reflected in oxygen, silicon, and aluminium being the three most common elements in the crust (in that order).

The lattice of oxygen atoms that results is usually close-packed, or close to it, with the charge being balanced by other cations in various different polyhedral sites according to size.

Zircon, ZrSiO4, demands eight-coordination of the ZrIV cations due to stoichiometry and because of their larger ionic radius (84 pm).

[15] Layer silicates, such as the clay minerals and the micas, are very common, and often are formed by horizontal cross-linking of metasilicate chains or planar condensation of smaller units.

Despite the double bond rule, stable organosilanethiones RR'Si=S have been made thanks to the stabilising mechanism of intermolecular coordination via an amine group.

It would make a promising ceramic if not for the difficulty of working with and sintering it: chemically, it is near-totally inert, and even above 1000 °C it keeps its strength, shape, and continues to be resistant to wear and corrosion.

[21] Reacting silyl halides with ammonia or alkylammonia derivatives in the gaseous phase or in ethanolic solution produces various volatile silylamides, which are silicon analogues of the amines:[21] Many such compounds have been prepared, the only known restriction being that the nitrogen is always tertiary, and species containing the SiH–NH group are unstable at room temperature.

[21] Silicon carbide (SiC) was first made by Edward Goodrich Acheson in 1891, who named it carborundum to reference its intermediate hardness and abrasive power between diamond (an allotrope of carbon) and corundum (aluminium oxide).

It is mostly used as an abrasive and a refractory material, as it is chemically stable and very strong, and it fractures to form a very sharp cutting edge.

For example, nucleophilic attack on silicon does not proceed by the SN2 or SN1 processes, but instead goes through a negatively charged true pentacoordinate intermediate and appears like a substitution at a hindered tertiary atom.

For example, enolates react at the carbon in haloalkanes, but at the oxygen in silyl chlorides; and when trimethylsilyl is removed from an organic molecule using hydroxide as a nucleophile, the product of the reaction is not the silanol as one would expect from using carbon chemistry as an analogy, because the siloxide is strongly nucleophilic and attacks the original molecule to yield the silyl ether hexamethyldisiloxane, (Me3Si)2O.

Trimethylsilyl triflate is in particular a very good Lewis acid and is used to convert carbonyl compounds to acetals and silyl enol ethers, reacting them together analogously to the aldol reaction.

In the laboratory, preparation is often carried out in small quantities by reacting tetrachlorosilane (silicon tetrachloride) with organolithium, Grignard, or organoaluminium reagents, or by catalytic addition of Si–H across C=C double bonds.

Organosilanes are made industrially by directly reacting alkyl or aryl halides with silicon with 10% by weight metallic copper as a catalyst.

Standard organic reactions suffice to produce many derivatives; the resulting organosilanes are often significantly more reactive than their carbon congeners, readily undergoing hydrolysis, ammonolysis, alcoholysis, and condensation to form cyclic oligomers or linear polymers.

They are fairly unreactive, but do react with concentrated solutions bearing the hydroxide ion and fluorinating agents, and occasionally, may even be used as mild reagents for selective syntheses.