Transcriptional regulation

It is orchestrated by transcription factors and other proteins working in concert to finely tune the amount of RNA being produced through a variety of mechanisms.

Bacteria and eukaryotes have very different strategies of accomplishing control over transcription, but some important features remain conserved between the two.

In the absence of other regulatory elements, a promoter's sequence-based affinity for RNA polymerases varies, which results in the production of different amounts of transcript.

[8] Sigma factors are specialized bacterial proteins that bind to RNA polymerases and orchestrate transcription initiation.

[10] RNA polymerase pauses occur frequently and are regulated by transcription factors, such as NusG and NusA, transcription-translation coupling, and mRNA secondary structure.

These mechanisms can be generally grouped into three main areas: All three of these systems work in concert to integrate signals from the cell and change the transcriptional program accordingly.

This difference is largely due to the compaction of the eukaryotic genome by winding DNA around histones to form higher order structures.

This compaction makes the gene promoter inaccessible without the assistance of other factors in the nucleus, and thus chromatin structure is a common site of regulation.

These factors are responsible for stabilizing binding interactions and opening the DNA helix to allow the RNA polymerase to access the template, but generally lack specificity for different promoter sites.

Once a polymerase is successfully bound to a DNA template, it often requires the assistance of other proteins in order to leave the stable promoter complex and begin elongating the nascent RNA strand.

Similarly, protein and nucleic acid factors can associate with the elongation complex and modulate the rate at which the polymerase moves along the DNA template.

This is accomplished by winding the DNA around protein octamers called histones, which has consequences for the physical accessibility of parts of the genome at any given time.

[20] Transcription factors are proteins that bind to specific DNA sequences in order to regulate the expression of a gene.

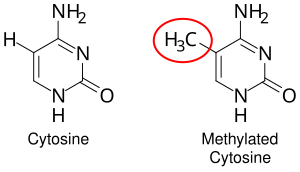

[25] The splice isoform DNMT3A2 behaves like the product of a classical immediate-early gene and, for instance, it is robustly and transiently produced after neuronal activation.

[26] Where the DNA methyltransferase isoform DNMT3A2 binds and adds methyl groups to cytosines appears to be determined by histone post translational modifications.

[30] Transcription factors are proteins that bind to specific DNA sequences in order to regulate the expression of a given gene.

[21] The power of transcription factors resides in their ability to activate and/or repress wide repertoires of downstream target genes.

Post-translational modifications to transcription factors located in the cytosol can cause them to translocate to the nucleus where they can interact with their corresponding enhancers.

Some post-translational modifications known to regulate the functional state of transcription factors are phosphorylation, acetylation, SUMOylation and ubiquitylation.

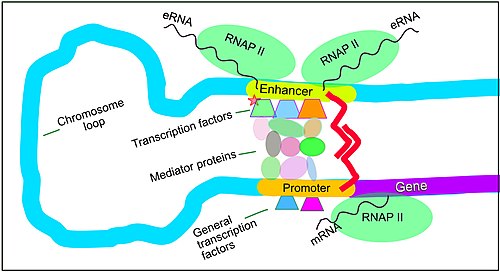

[37] Among this constellation of sequences, enhancers and their associated transcription factor proteins have a leading role in the regulation of gene expression.

[39] The schematic illustration in this section shows an enhancer looping around to come into close physical proximity with the promoter of a target gene.

[42] Enhancers, when active, are generally transcribed from both strands of DNA with RNA polymerases acting in two different directions, producing two eRNAs as illustrated in the Figure.

[46] Chromosome conformation capture (3C) and more recently Hi-C techniques provided evidence that active chromatin regions are “compacted” in nuclear domains or bodies where transcriptional regulation is enhanced.

Cell-fate decisions are mediated upon highly dynamic genomic reorganizations at interphase to modularly switch on or off entire gene regulatory networks through short to long range chromatin rearrangements.

TAD boundaries are often composed by housekeeping genes, tRNAs, other highly expressed sequences and Short Interspersed Elements (SINE).

The specific molecules identified at boundaries of TADs are called insulators or architectural proteins because they not only block enhancer leaky expression but also ensure an accurate compartmentalization of cis-regulatory inputs to the targeted promoter.

Particularly for Pol II, much of the regulatory checkpoints in the transcription process occur in the assembly and escape of the pre-initiation complex.

This assembly is marked by the post-translational modification (typically phosphorylation) of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of Pol II through a number of kinases.

[55] The CTD is a large, unstructured domain extending from the RbpI subunit of Pol II, and consists of many repeats of the heptad sequence YSPTSPS.

TFIIH, the helicase that remains associated with Pol II throughout transcription, also contains a subunit with kinase activity which will phosphorylate the serines 5 in the heptad sequence.