Causes of the Great Recession

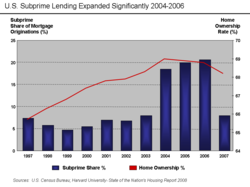

The major causes of the initial subprime mortgage crisis and the following recession include lax lending standards contributing to the real-estate bubbles that have since burst; U.S. government housing policies; and limited regulation of non-depository financial institutions.

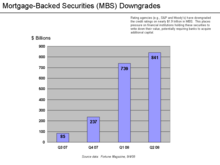

When global credit markets essentially stopped funding mortgage-related investments in the 2007–2008 period, U.S. homeowners were no longer able to refinance and defaulted in record numbers, leading to the collapse of securities backed by these mortgages that now pervaded the system.

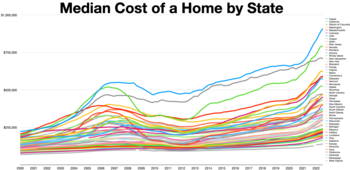

Furthermore, the authors argued that the trend in worsening loan quality was harder to detect with rising housing prices, as more refinancing options were available, keeping the default rate lower.

[49] A 2009 paper identifies twelve economists and commentators who, between 2000 and 2006, predicted a recession based on the collapse of the then-booming housing market in the United States:[50] Dean Baker, Wynne Godley, Fred Harrison, Michael Hudson, Eric Janszen, Med Jones[51] Steve Keen, Jakob Brøchner Madsen, Jens Kjaer Sørensen, Kurt Richebächer, Nouriel Roubini, Peter Schiff, and Robert Shiller.

"[53] Economist Stan Leibowitz argued in The Wall Street Journal that the extent of equity in the home was the key factor in foreclosure, rather than the type of loan, credit worthiness of the borrower, or ability to pay.

Research by Raghuram Rajan indicated that: "Starting in the early 1970s, advanced economies found it increasingly difficult to grow...the shortsighted political response to the anxieties of those falling behind was to ease their access to credit.

The takeover is another example of attempts to stop the dominoes from falling.There was a real irony in the recent intervention by the Federal Reserve System to provide the money that enabled the firm of JPMorgan Chase to buy Bear Stearns before it went bankrupt.

[81] One 2017 NBER study argued that real estate investors (i.e., those owning 2+ homes) were more to blame for the crisis than subprime borrowers: "The rise in mortgage defaults during the crisis was concentrated in the middle of the credit score distribution, and mostly attributable to real estate investors" and that "credit growth between 2001 and 2007 was concentrated in the prime segment, and debt to high-risk [subprime] borrowers was virtually constant for all debt categories during this period."

[82] A 2011 Fed study had a similar finding: "In states that experienced the largest housing booms and busts, at the peak of the market almost half of purchase mortgage originations were associated with investors.

The Fed study reported that mortgage originations to investors rose from 25% in 2000 to 45% in 2006, for Arizona, California, Florida, and Nevada overall, where housing price increases during the bubble (and declines in the bust) were most pronounced.

[83] Nicole Gelinas of the Manhattan Institute described the negative consequences of not adjusting tax and mortgage policies to the shifting treatment of a home from conservative inflation hedge to speculative investment.

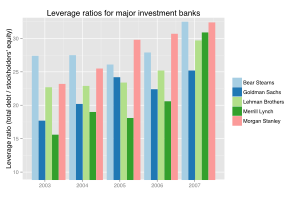

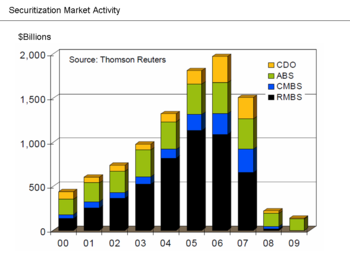

[91] A 2004 SEC decision related to the net capital rule allowed USA investment banks to issue substantially more debt, which was then used to help fund the housing bubble through purchases of mortgage-backed securities.

Lehman Brothers was liquidated, Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch were sold at fire-sale prices, and Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley became commercial banks, subjecting themselves to more stringent regulation.

At the same time, weak underwriting standards, unsound risk management practices, increasingly complex and opaque financial products, and consequent excessive leverage combined to create vulnerabilities in the system.

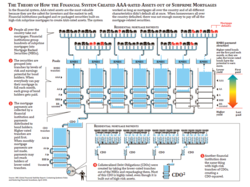

"[105] Princeton professor Harold James wrote that one of the byproducts of this innovation was that MBS and other financial assets were "repackaged so thoroughly and resold so often that it became impossible to clearly connect the thing being traded to its underlying value."

[99] In addition, Chicago Public Radio and the Huffington Post reported in April 2010 that market participants, including a hedge fund called Magnetar Capital, encouraged the creation of CDO's containing low quality mortgages, so they could bet against them using CDS.

Author Robin Blackburn explained how they worked:[91] Institutional investors could be persuaded to buy the SIV's supposedly high-quality, short-term commercial paper, allowing the vehicles to acquire longer-term, lower quality assets, and generating a profit on the spread between the two.

The latter included larger amounts of mortgages, credit-card debt, student loans and other receivables...For about five years those dealing in SIV's and conduits did very well by exploiting the spread...but this disappeared in August 2007, and the banks were left holding a very distressed baby.

These institutions had become so big that the failure of just one of them would pose a systemic risk.By contrast, some scholars have argued that fragmentation in the mortgage securitization market led to increased risk taking and a deterioration in underwriting standards.

[138][139] In 1992, the Democratic-controlled 102nd Congress under the George H. W. Bush administration weakened regulation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac with the goal of making available more money for the issuance of home loans.

The Washington Post wrote: "Congress also wanted to free up money for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy mortgage loans and specified that the pair would be required to keep a much smaller share of their funds on hand than other financial institutions.

He described the significance of these entities: "In early 2007, asset-backed commercial paper conduits, in structured investment vehicles, in auction-rate preferred securities, tender option bonds and variable rate demand notes, had a combined asset size of roughly $2.2 trillion.

[153] The Economist reported in March 2010: "Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers were non-banks that were crippled by a silent run among panicky overnight "repo" lenders, many of them money market funds uncertain about the quality of securitized collateral they were holding.

[35] Key examples of regulatory failures include: Author Roger Lowenstein summarized some of the regulatory problems that caused the crisis in November 2009: "1) Mortgage regulation was too lax and in some cases nonexistent; 2) Capital requirements for banks were too low; 3) Trading in derivatives such as credit default swaps posed giant, unseen risks; 4) Credit ratings on structured securities such as collateralized-debt obligations were deeply flawed; 5) Bankers were moved to take on risk by excessive pay packages; 6) The government’s response to the crash also created, or exacerbated, moral hazard.

A November 2009 report from economists of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) writing independently of that organization indicated that: The study concluded that: "the prevention of future crises might require weakening political influence of the financial industry or closer monitoring of lobbying activities to understand better the incentives behind it.

"[179] A 2012 book by Hedrick Smith, Who Stole the American Dream?, suggests that the Powell Memo was instrumental in setting a new political direction for US business leaders that led to "America’s contemporary economic malaise.

[187] But in fact, a 2009 paper identifies twelve economists and commentators who, between 2000 and 2006, predicted a recession based on the collapse of the then-booming housing market in the United States:[50] Dean Baker, Wynne Godley, Fred Harrison, Michael Hudson, Eric Janszen, Med Jones[51] Steve Keen, Jakob Brøchner Madsen, Jens Kjaer Sørensen, Kurt Richebächer, Nouriel Roubini, Peter Schiff, and Robert Shiller.

[193] Another probable cause of the crisis—and a factor that unquestionably amplified its magnitude—was widespread miscalculation by banks and investors of the level of risk inherent in the unregulated collateralized debt obligation and credit default swap markets.

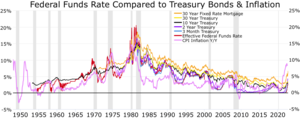

Under this theory, banks and investors systematized the risk by taking advantage of low interest rates to borrow tremendous sums of money that they could only pay back if the housing market continued to increase in value.

"[196] Hamilton's own model, a time-series econometric forecast based on data up to 2003, showed that the decline in GDP could have been successfully predicted to almost its full extent given knowledge of the price of oil.