Diatom

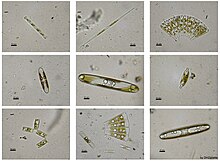

A diatom (Neo-Latin diatoma)[a] is any member of a large group comprising several genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world.

[16] In the presence of adequate nutrients and sunlight, an assemblage of living diatoms doubles approximately every 24 hours by asexual multiple fission; the maximum life span of individual cells is about six days.

Research on the dinoflagellates Durinskia baltica and Glenodinium foliaceum has shown that the endosymbiont event happened so recently, evolutionarily speaking, that their organelles and genome are still intact with minimal to no gene loss.

Diatoms are protists that form massive annual spring and fall blooms in aquatic environments and are estimated to be responsible for about half of photosynthesis in the global oceans.

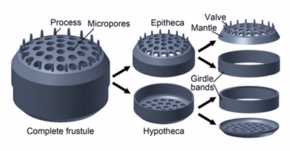

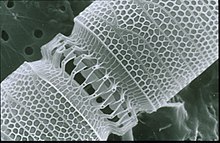

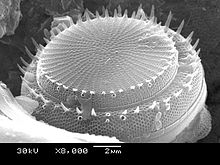

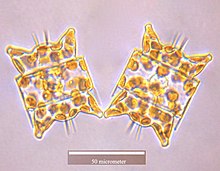

[35]: 25–30 This siliceous wall[36] can be highly patterned with a variety of pores, ribs, minute spines, marginal ridges and elevations; all of which can be used to delineate genera and species.

Once such cells reach a certain minimum size, rather than simply divide, they reverse this decline by forming an auxospore, usually through meiosis and sexual reproduction, but exceptions exist.

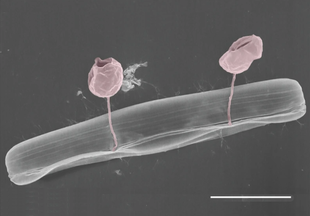

[44] The silica deposition that takes place from the membrane bound vesicle in diatoms has been hypothesized to be a result of the activity of silaffins and long chain polyamines.

One hypothesis as to how these proteins work to create complex structure is that residues are conserved within the SDV's, which is unfortunately difficult to identify or observe due to the limited number of diverse sequences available.

[47] The viewer decided that it was a plant because the parallelograms didn't separate upon agitation, nor did they vary in appearance when dried or subjected to warm water (in an attempt to dissolve the "salt").

[53][54][55] More recent reports describe the identification of novel components involved in higher order processes, the dynamics documented through real-time imaging, and the genetic manipulation of silica structure.

[56][57] The approaches established in these recent works provide practical avenues to not only identify the components involved in silica cell wall formation but to elucidate their interactions and spatio-temporal dynamics.

[62] Certain species of bacteria in oceans and lakes can accelerate the rate of dissolution of silica in dead and living diatoms by using hydrolytic enzymes to break down the organic algal material.

When conditions in the upper mixed layer (nutrients and light) are favourable (as at the spring), their competitive edge and rapid growth rate[74] enables them to dominate phytoplankton communities ("boom" or "bloom").

[80] When conditions turn unfavourable, usually upon depletion of nutrients, diatom cells typically increase in sinking rate and exit the upper mixed layer ("bust").

Sinking out of the upper mixed layer removes diatoms from conditions unfavourable to growth, including grazer populations and higher temperatures (which would otherwise increase cell metabolism).

Because of this bloom-and-bust cycle, diatoms are believed to play a disproportionately important role in the export of carbon from oceanic surface waters[81][82] (see also the biological pump).

Other researchers[85] have suggested that the biogenic silica in diatom cell walls acts as an effective pH buffering agent, facilitating the conversion of bicarbonate to dissolved CO2 (which is more readily assimilated).

[87][88][89] Subsequently, the cycle appears dominated (and more strongly regulated) by the radiolarians and siliceous sponges, the former as zooplankton, the latter as sedentary filter-feeders primarily on the continental shelves.

Despite this low level of CO2 in the ocean and its slow diffusion rate in water, diatoms fix 10–20 GtC annually via photosynthesis thanks to their carbon dioxide concentrating mechanisms, allowing them to sustain marine food chains.

In addition, 0.1–1% of this organic material produced in the euphotic layer sinks down as particles, thus transferring the surface carbon toward the deep ocean and sequestering atmospheric CO2 for thousands of years or longer.

However, in diatoms the urea cycle appears to play a role in exchange of nutrients between the mitochondria and the cytoplasm, and potentially the plastid [100] and may help to regulate ammonium metabolism.

The earliest known fossil diatoms date from the early Jurassic (~185 Ma ago),[118] although the molecular clock[118] and sedimentary[119] evidence suggests an earlier origin.

The expansion of grassland biomes and the evolutionary radiation of grasses during the Miocene is believed to have increased the flux of soluble silicon to the oceans, and it has been argued that this promoted the diatoms during the Cenozoic era.

Peaks in opal productivity in the marine isotope stage are associated with the breakdown of the regional halocline stratification and increased nutrient supply to the photic zone.

[151] However, phylogenomic analyses of diatom proteomes and chromalveolate evolutionary history will likely take advantage of complementary genomic data from under-sequenced lineages such as red algae.

The phleomycin/zeocin resistance gene Sh Ble is commonly used as a selection marker,[152][155] and various transgenes have been successfully introduced and expressed in diatoms with stable transmissions through generations,[154][155] or with the possibility to remove it.

[155] Furthermore, these systems now allow the use of the CRISPR-Cas genome edition tool, leading to a fast production of functional knock-out mutants[155][156] and a more accurate comprehension of the diatoms' cellular processes.

With an appropriate artificial selection procedure, diatoms that produce valves of particular shapes and sizes might be evolved for cultivation in chemostat cultures to mass-produce nanoscale components.

The infusoria that Darwin later noted in the face paint of Fueguinos, native inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego in the southern end of South America, were later identified in the same way.

In the fourth edition of On the Origin of Species, he wrote, "Few objects are more beautiful than the minute siliceous cases of the diatomaceae: were these created that they might be examined and admired under the high powers of the microscope?"

Displays overlays from four fluorescent channels

(b) Cyan: [PLL-A546 fluorescence] - generic counterstain for visualising eukaryotic cell surfaces

(c) Blue: [Hoechst fluorescence] - stains DNA, identifies nuclei

(d) Red: [chlorophyll autofluorescence] - resolves chloroplasts [ 27 ]

- Central nodule

- Striae; pores, punctae, spots or dots in a line on the surface that allow nutrients in, and waste out, of the cell

- Areola ; hexagonal or polygonal boxlike perforation with a sieve present on the surface of diatom

- Raphe ; slit in the valves

- Polar nodule; thickening of wall at the distal ends of the raphe [ 37 ] [ 38 ]

- Frustule ; hard and porous cell wall

- Pyrenoid ; center of carbon fixation

- Plastid membranes (4, secondary red)

- Inner membranes

- Thylakoid ; site of the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis

- Oil body ; storage for triacylglycerols [ 39 ]

- Mitochondrion ; creates ATP (energy) for the cell

- Vacuoles ; vesicle of a cell that contains fluid bound by a membrane

- Cytoplasmic strand; holds the nucleus

- Protoplasmic bridge

- Epivalve

- Nucleus ; holds the genetic material

- Endoplasmic reticulum , the transport network for molecules going to specific parts of the cell

- Golgi apparatus ; modifies proteins and sends them out of the cell

- Epicingulum

- Hypocingulum

- Hypovalve

- Microtubule centre

This projection of a stack of confocal images shows the diatoms' cell wall (cyan), chloroplasts (red), DNA (blue), membranes and organelles (green).

versus silicate concentration [ 73 ]

Stephanodiscus hantzschii

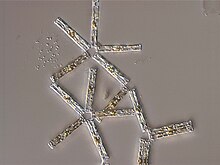

Isthmia nervosaIsthmia nervosa

Odontella aurita