Victor Frankenstein

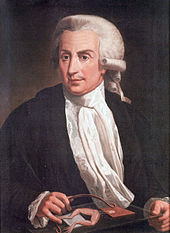

Certainly, the author and people in her environment were aware of the experiment on electricity and dead tissues by Luigi Galvani and his nephew Giovanni Aldini and the work of Alessandro Volta at the University of Pavia.

[1] There is speculation that Percy was one of Mary Shelley's models for Victor Frankenstein; while a student at Eton College, he had "experimented with electricity and magnetism as well as with gunpowder and numerous chemical reactions", and his rooms at the University of Oxford were filled with scientific equipment.

One of the characters of François-Félix Nogaret [fr]'s novella Le Miroir des événements actuels ou la Belle au plus offrant, published in 1790, is an inventor named "Wak-wik-vauk-an-son-frankésteïn",[5] then abridged as "Frankésteïn", but there is no proof Shelley had read it.

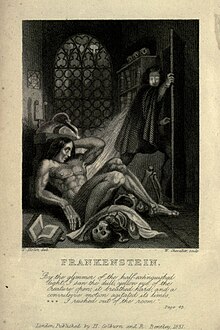

His creature, upon discovering the death of his creator, is overcome by sorrow and guilt and vows to commit suicide by burning himself alive in "the Northernmost extremity of the globe;" he then disappears, never to be seen or heard from again.

[21][N 1] Mary Shelley did not invent the expression, which had already been used in the early 18th century and, closer to its end, by Immanuel Kant,[22] and Frankenstein goes far beyond the technical substratum, presenting, in addition to its borrowings from myth, metaphysical, aesthetic and ethical aspects.

[30] The novel also contains hints of Don Juanism: the hero's quest is never satisfied and, like the statue of the commander,[31] the monster appears and precipitates Frankenstein into the bowels of a psychological hell,[32] whose fire is the "bite" of glaciation.

As a Titan, he enjoys immortality, and his punishment, according to Aeschylus, is to be chained to Mount Caucasus in India and tortured by the eagle, which gnaws away at his liver every day, regenerating it at night.

Prometheus Unbound, a four-act play depicting the Titan, more or less mingled with the Lucifer of Milton's Paradise Lost, a champion of moral and humanitarian virtues, freed from the yoke of Jupiter and heralding the liberation of mankind.

[41] Shelley's stubborn belief in the ultimate triumph of love and the avenue of the Golden Age[N 4] is fulfilled in the victory over Evil of a hero free of all taint and entirely worthy of representing the Good.

The third point is undoubtedly the allegory of the chained Titan's suffering:[46] such is Victor's mortifying despair, walled in by his silence and pain; such is also the absolute solitude of the monster rejected by his creator and the common man,[N 5] deprived of his feminine complement;[46] such is finally, albeit to a lesser degree, the growing anxiety which, little by little, undermines the youthful and initially conquering enthusiasm of Robert Walton,[47] alienated from his family, his crew and the commerce of men.

Beyond the original meaning of Ovid's title, for there is more to it than a "change of form" (Meta-morphoses: In noua fert animus mutatas dicere formas / Corpora),[51] this is an act of creation, but with a technique, materials and energy.

[53][54] He succeeded in what the scientists of the time hoped one day to achieve, in fact the old foolish dream of the alchemists; the idea, the imagination, the enthusiasm, it was first Cornelius Agrippa[55] and Paracelsus,[56][57] then more rationally, Professor Waldman, no doubt inspired Mary Shelley by Humphry Davy,[58][59] writing in 1816: "science has conferred on him [man] powers that might almost be called creative [...] to interrogate nature [...] in mastery [...], and to penetrate its deepest secrets"; fiction erases Humphry Davy's "almost" and takes the plunge.

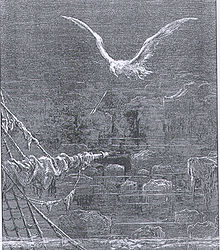

[40] In addition to these two versions of the Prometheus myth, there are borrowings from Milton's Paradise Lost,[64] often mentioned in the Shelleys' diaries,[65] particularly when William Godwin published his work on the poet's nephews,[66] and from Coleridge's poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

[N 8][69][70] Like Coleridge's sailor, Victor has destroyed the divine order and has remained abandoned by God,[71] solitary, deprived of certainties, on icy continents in the image of the glaciation from which his soul suffers.

So he puts his body in unison with his soul and entrusts it to the inaccessible peaks and icy deserts that respond to the coldness of his heart, dragging along his pursuer, who is no longer sure whether he is hunter or game.

The vocabulary used by Victor, who is not Mary Shelley's spokesman,[46] as he constructs his narrative by restructuring his life and putting it into perspective in the light of what he has retained from it, with its weaknesses, its emotional burdens, its weight of character, is limited to a semantics of research and discovery.

Admittedly, the process responds to a possibility evoked by certain eighteenth-century scientists; however, there is a desacralization of the human being, a corruption of his integrity, a defilement of his purity,[32] all in the light of a Judeo-Christian vision of Man.

[41] One of the functions of nature in Frankenstein is to suggest, if only on a sensory and perceptual level, the presence of transcendence - harmony in the Rhine valley, sovereign grandeur atop the Alpine peaks, infinity and eternity on the icy oceans.

"[82] "I know of nothing sublime which is not some modification of power"[78] "[…] strength, violence, pain and terror, are ideas that rush in upon the mind together"[78] Mary Shelley uses the ingredients analyzed or simply listed by Burke to associate Victor Frankenstein's transgression with the notion of the sublime, either to make him describe his states of mind, whether inhabited by torment or exaltation,[83] or to create the illusion that landscapes impose notions of greatness and disquiet, elevation or unease[77] (steep valleys, dark forests, etc.

The monster, too, is sublime in its conception (obscurity, isolation), its size (out of the ordinary and frightening), the places it chooses and imposes on Victor (forests, peaks, valleys, abysses, vast deserts, tumultuous or frozen oceans), the unspeakable absoluteness of its solitude, the extremity of its feelings, the unpredictability of its character,[77] its alliance with the elements (storms, glaciers, darkness, earth, water, fire).

[84] Soon, the inner landscape becomes nocturnal, on the edge of consciousness, a dark, convulsive, spasmodic turmoil; through a play of mirrors reminiscent of the nested, reflective structure, the monster to which Victor has nevertheless given life becomes the very projection of his death wish.

The transgression has been placed under the sign of Thanatos: the monster is the negative double of his creator,[85] his evil Doppelgänger[86] who carries out the death sentence unconsciously pronounced by Victor[47] on his family, his friend, his wife, whom he believes he adores but whom he has experienced as castrating, suffocating him with love, protection, moral comfort and social certainties.

At times, she approaches the narrators - who are never protagonists in the raw, since all actions belong to the past and are filtered through a network of successive consciousnesses - only to distance herself from them in a constant game of hide-and-seek, swaying to the whim of her irony.

Admittedly, this is a kind of stark representation of the romantic hero,[90] but through the repetition of attacks and crises, the portrait of a character that psychiatry would call bipolar gradually emerges, rather unlike his creator.

[46] His acts of contrition are easily contrasted, as adisplayed at the beginning of his story, with, for example, the fiery heroic-comic speech he addresses to Walton's sailors, in which he enjoins upon them the firmness of a grand design and the duty of heroism.

[93] Then she's framed by bouts of deep despondency (sunk in languor); only Walton, captivated by the character, falls under her spell: "a voice so modulated", "an eye so full of lofty design and heroism".

Frankenstein is, among other things, a matter of crime and punishment,[23] the systematic destruction of his family's relational and moral fabric, the disintegration of his being through isolation, guilt, inner torture[52] and, ultimately, the extinction of life.

[21] So to claim that the enterprise itself is not reprehensible is a sophism: the tragic personal consequences, the upheaval of institutions, the absurd operation of justice,[48] which condemns on the basis of appearances,[94] are the result of flawed premises.

[47] Mary Shelley's prophetic intuition is to be commended, as she inserts herself into a Gothic tradition that is almost on the wane, renewing the genre[98] but, above all, forcing it to pose one of mankind's major problems - that of its own limits.

[96] As technology continues to evolve much faster than morality, the duty of the human community, she shows, is to define and set the methods and constraints necessary to ensure that the boundaries of the possible remain unbroken.