Early Netherlandish painting

The term "Early Netherlandish art" applies broadly to painters active during the 15th and 16th centuries[2] in the northern European areas controlled by the Dukes of Burgundy and later the Habsburg dynasty.

[11] These arguments and distinctions dissipated after World War I, and following the leads of Friedländer, Panofsky, and Pächt, English-language scholars now almost universally describe the period as "Early Netherlandish painting", although many art historians view the Flemish term as more correct.

They were followed by panel painters such as Melchior Broederlam and Robert Campin, the latter generally considered the first Early Netherlandish master, under whom van der Weyden served his apprenticeship.

[15] Johan Huizinga said that art of the era was meant to be fully integrated with daily routine, to "fill with beauty" the devotional life in a world closely tied to the liturgy and sacraments.

Two events symbolically and historically reflect this shift: the transporting of a marble Madonna and Child by Michelangelo to Bruges in 1506,[13] and the arrival of Raphael's tapestry cartoons to Brussels in 1517, which were widely seen while in the city.

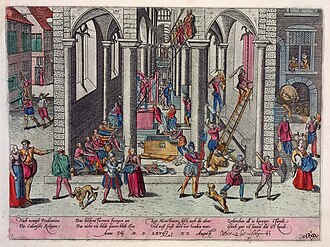

There was considerable overlap, and the early- to mid-16th-century innovations can be tied to the Mannerist style, including naturalistic secular portraiture, the depiction of ordinary (as opposed to courtly) life, and the development of elaborate landscapes and cityscapes that were more than background views.

[21] This was first seen in manuscript illumination, which after 1380 conveyed new levels of realism, perspective and skill in rendering colour,[22] peaking with the Limbourg brothers and the Netherlandish artist known as Hand G, to whom the most significant leaves of the Turin-Milan Hours are usually attributed.

According to Georges Hulin de Loo, Hand G's contributions to the Turin-Milan Hours "constitute the most marvelous group of paintings that have ever decorated any book, and, for their period, the most astounding work known to the history of art".

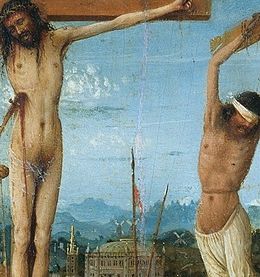

The more prosaic elements would be left to assistants; in many works it is possible to discern abrupt shifts in style, with the relatively weak Deesis passage in van Eyck's Crucifixion and Last Judgement diptych being a better-known example.

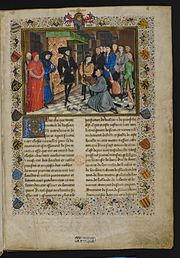

[72] Philip the Good followed the example set earlier in France by his great-uncles including Jean, Duke of Berry by becoming a strong patron of the arts and commissioning a large number of artworks.

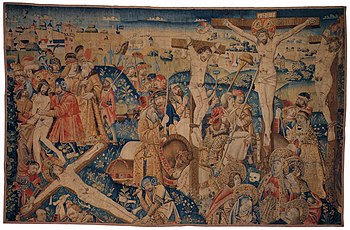

"[86] This blend of the earthly and heavenly evidences van Eyck's belief that the "essential truth of Christian doctrine" can be found in "the marriage of secular and sacred worlds, of reality and symbol".

[87] He depicts overly large Madonnas, whose unrealistic size shows the separation between the heavenly from earthly, but placed them in everyday settings such as churches, domestic chambers or seated with court officials.

The symbols were often subtly woven into the paintings so that they only became apparent after close and repeated viewing,[82] while much of the iconography reflects the idea that, according to John Ward, there is a "promised passage from sin and death to salvation and rebirth".

According to Harbison, van der Weyden incorporated his symbols so carefully, and in such an exquisite manner, that "Neither the mystical union that results in his work, nor his reality itself for that matter, seems capable of being rationally analyzed, explained or reconstructed.

[100] According to art historian Susie Nash, by the early 16th century, the region led the field in almost every aspect of portable visual culture, "with specialist expertise and techniques of production at such a high level that no one else could compete with them".

[104] Before the mid-15th century, illuminated books were considered a higher form of art than panel painting, and their ornate and luxurious qualities better reflected the wealth, status and taste of their owners.

The single leaves had other uses rather than inserts; they could be attached to walls as aids to private meditation and prayer,[107] as seen in Christus' 1450–60 panel Portrait of a Young Man, now in the National Gallery, which shows a small leaf with text to the Vera icon illustrated with the head of Christ.

The Burgundian book-collecting tradition passed to Philip's son and his wife, Charles the Bold and Margaret of York; his granddaughter Mary of Burgundy and her husband Maximilian I; and to his son-in-law, Edward IV, who was an avid collector of Flemish manuscripts.

In central panels the mid-ground was populated by members of the Holy Family; early works, especially from the Sienese or Florentine traditions, were overwhelmingly characterised by images of the enthroned Virgin set against a gilded background.

This was in part because they produced at a lower cost, allocating different portions of the panels among specialised workshop members, a practice Borchert describes as an early form of division of labour.

Van Eyck was the pioneer;[150] his seminal 1432 Léal Souvenir is one of the earliest surviving examples, emblematic of the new style in its realism and acute observation of the small details of the sitter's appearance.

As well as connecting the style to the later Age of Discovery, the role of Antwerp as a booming centre both of world trade and cartography, and the wealthy town-dweller's view of the countryside, art historians have explored the paintings as religious metaphors for the pilgrimage of life.

This also explains why a number of later Netherlandish artists became associated with, in the words of art historian Rolf Toman, "picturesque gables, bloated, barrel-shaped columns, droll cartouches, 'twisted' figures, and stunningly unrealistic colours – actually employ[ing] the visual language of Mannerism".

This reduced number in part follows from the identification of other mid-15th-century painters such as van der Weyden, Christus and Memling,[200] while Hubert, so highly regarded by late-19th-century critics, is now relegated as a secondary figure with no works definitively attributed to him.

Yet it remained popular in some royal art collections; Mary of Hungary and Philip II of Spain both sought out Netherlandish painters, sharing a preference for van der Weyden and Bosch.

[M] These works had a profound effect on German literary critic and philosopher Karl Schlegel, who after a visit in 1803 wrote an analysis of Netherlandish art, sending it to Ludwig Tieck, who had the piece published in 1805.

[206] In 1821 Johanna Schopenhauer became interested in the work of Jan van Eyck and his followers, having seen early Netherlandish and Flemish paintings in the collection of the brothers Sulpiz and Melchior Boisserée in Heidelberg.

Waagen went on to become director of the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, amassing a collection of Netherlandish art, including most of the Ghent panels, a number of van der Weyden triptychs, and a Bouts altarpiece.

[206] In 1830 the Belgian Revolution split Belgium from the Netherlands of today; as the newly created state sought to establish a cultural identity, Memling's reputation came to equal that of van Eyck in the 19th century.

[210][211] At a period when London's National Gallery sought to increase its prestige,[212] Charles Eastlake purchased Rogier van der Weyden's The Magdalen Reading panel in 1860 from Edmond Beaucousin's "small but choice" collection of early Netherlandish paintings.