Ligand field theory

Ligand field theory (LFT) describes the bonding, orbital arrangement, and other characteristics of coordination complexes.

Griffith and Orgel used the electrostatic principles established in crystal field theory to describe transition metal ions in solution and used molecular orbital theory to explain the differences in metal-ligand interactions, thereby explaining such observations as crystal field stabilization and visible spectra of transition metal complexes.

In their paper, they proposed that the chief cause of color differences in transition metal complexes in solution is the incomplete d orbital subshells.

[6] That is, the unoccupied d orbitals of transition metals participate in bonding, which influences the colors they absorb in solution.

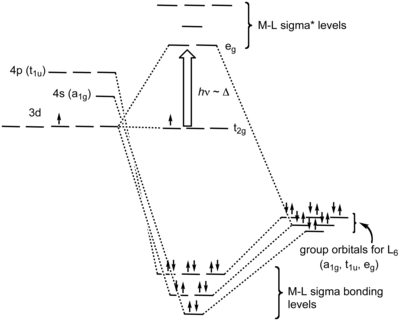

[6] In an octahedral complex, the molecular orbitals created by coordination can be seen as resulting from the donation of two electrons by each of six σ-donor ligands to the d-orbitals on the metal.

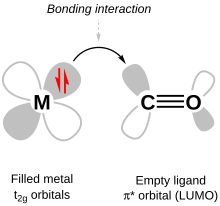

It is filled with electrons from the metal d-orbitals, however, becoming the HOMO (highest occupied molecular orbital) of the complex.

The greater stabilization that results from metal-to-ligand bonding is caused by the donation of negative charge away from the metal ion, towards the ligands.

The energy difference between the latter two types of MOs is called ΔO (O stands for octahedral) and is determined by the nature of the π-interaction between the ligand orbitals with the d-orbitals on the central atom.

A small ΔO can be overcome by the energetic gain from not pairing the electrons, leading to high-spin.

The spectrochemical series is an empirically-derived list of ligands ordered by the size of the splitting Δ that they produce.