Liquid

A liquid is a nearly incompressible fluid that conforms to the shape of its container but retains a nearly constant volume independent of pressure.

Important everyday liquids include aqueous solutions like household bleach, other mixtures of different substances such as mineral oil and gasoline, emulsions like vinaigrette or mayonnaise, suspensions like blood, and colloids like paint and milk.

[13] In machining, water and oils are used to remove the excess heat generated, which can quickly ruin both the work piece and the tooling.

[15] Liquid is the primary component of hydraulic systems, which take advantage of Pascal's law to provide fluid power.

[16] Liquid metals have several properties that are useful in sensing and actuation, particularly their electrical conductivity and ability to transmit forces (incompressibility).

[17][18] The metal gallium is considered to be a promising candidate for these applications as it is a liquid near room temperature, has low toxicity, and evaporates slowly.

Because liquids have little elasticity they can literally be pulled apart in areas of high turbulence or dramatic change in direction, such as the trailing edge of a boat propeller or a sharp corner in a pipe.

This causes liquid to fill the cavities left by the bubbles with tremendous localized force, eroding any adjacent solid surface.

Most common liquids have tensions ranging in the tens of mJ/m2, so droplets of oil, water, or glue can easily merge and adhere to other surfaces, whereas liquid metals such as mercury may have tensions ranging in the hundreds of mJ/m2, thus droplets do not combine easily and surfaces may only wet under specific conditions.

The surface tensions of common liquids occupy a relatively narrow range of values when exposed to changing conditions such as temperature, which contrasts strongly with the enormous variation seen in other mechanical properties, such as viscosity.

A Newtonian liquid exhibits a linear strain/stress curve, meaning its viscosity is independent of time, shear rate, or shear-rate history.

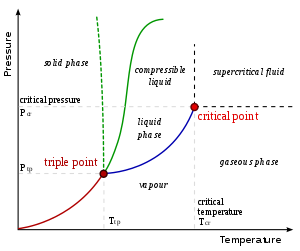

[38] At a temperature below the boiling point, any matter in liquid form will evaporate until reaching equilibrium with the reverse process of condensation of its vapor.

However, this is only true under constant pressure, so that (for example) water and ice in a closed, strong container might reach an equilibrium where both phases coexist.

Since the pressure is essentially zero (except on surfaces or interiors of planets and moons) water and other liquids exposed to space will either immediately boil or freeze depending on the temperature.

A familiar example of an emulsion is mayonnaise, which consists of a mixture of water and oil that is stabilized by lecithin, a substance found in egg yolks.

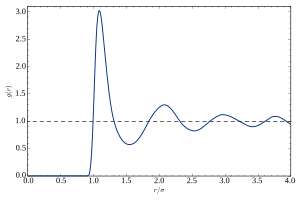

Conversely, although the molecules in solids are densely packed, they usually fall into a regular structure, such as a crystalline lattice (glasses are a notable exception).

Due to the relative importance of thermal fluctuations in liquids (compared with solids), these structures are highly dynamic, continuously deforming, breaking, and reforming.

[54] The competition between energy and entropy makes liquids difficult to model at the molecular level, as there is no idealized "reference state" that can serve as a starting point for tractable theoretical descriptions.

However, under standard conditions (near room temperature and pressure), much of the macroscopic behavior of liquids can be understood in terms of classical mechanics.

[54][56] The "classical picture" posits that the constituent molecules are discrete entities that interact through intermolecular forces according to Newton's laws of motion.

[54] For the classical limit to apply, a necessary condition is that the thermal de Broglie wavelength, is small compared with the length scale under consideration.

A notable example is hydrogen bonding in associated liquids like water,[59][60] where, due to the small mass of the proton, inherently quantum effects such as zero-point motion and tunneling are important.

For room-temperature liquids, the right-hand side is about 10−14 seconds, which generally means that time-dependent processes involving translational motion can be described classically.

Due to their low temperature and mass, such liquids have a thermal de Broglie wavelength comparable to the average distance between molecules.

According to linear response theory, the Fourier transform of K or G describes how the system returns to equilibrium after an external perturbation; for this reason, the dispersion step in the GHz to THz region is also called relaxation.

[64][65] Empirical correlations are simple mathematical expressions intended to approximate a liquid's properties over a range of experimental conditions, such as varying temperature and pressure.

However, they require high quality experimental data to obtain a good fit and cannot reliably extrapolate beyond the conditions covered by experiments.

[70] Hydrodynamic theories describe liquids in terms of space- and time-dependent macroscopic fields, such as density, velocity, and temperature.

Conceptually, it is based on the Boltzmann equation for dilute gases, where the dynamics of a molecule consists of free motion interrupted by discrete binary collisions, but it is also applied to liquids.

[57] In contrast with classical molecular dynamics, the intermolecular force fields are an output of the calculation, rather than an input based on experimental measurements or other considerations.