Macrophage

They take various forms (with various names) throughout the body (e.g., histiocytes, Kupffer cells, alveolar macrophages, microglia, and others), but all are part of the mononuclear phagocyte system.

[22] The removal of dying cells is, to a greater extent, handled by fixed macrophages, which will stay at strategic locations such as the lungs, liver, neural tissue, bone, spleen and connective tissue, ingesting foreign materials such as pathogens and recruiting additional macrophages if needed.

[26] Two of the main roles of the tissue resident macrophages are to phagocytose incoming antigen and to secrete proinflammatory cytokines that induce inflammation and recruit other immune cells to the site.

[27][32] Recognition of MAMPs by PRRs can activate tissue resident macrophages to secrete proinflammatory cytokines that recruit other immune cells.

[26][27] Additionally, activated macrophages have been found to have delayed synthesis of prostaglandins (PGs) which are important mediators of inflammation and pain.

[41] The macrophages in lymphoid tissues are more involved in ingesting antigens and preventing them from entering the blood, as well as taking up debris from apoptotic lymphocytes.

[46][34] These 2 signals activate the macrophages and enhance their ability to kill intracellular pathogens through increased production of antimicrobial molecules such as nitric oxide (NO) and superoxide (O2-).

[42][47] TH2 cells play an important role in alternative macrophage activation as part of type 2 immune response against large extracellular pathogens like helminths.

[34][50] Another part of the adaptive immunity activation involves stimulating CD8+ via cross presentation of antigens peptides on MHC class I molecules.

[27][51][43] Macrophages have been shown to secrete cytokines BAFF and APRIL, which are important for plasma cell isotype switching.

M1 macrophages are the dominating phenotype observed in the early stages of inflammation and are activated by four key mediators: interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs).

[59][60][61] These early-invading, phagocytic macrophages reach their highest concentration about 24 hours following the onset of some form of muscle cell injury or reloading.

It is thought that macrophages release soluble substances that influence the proliferation, differentiation, growth, repair, and regeneration of muscle, but at this time the factor that is produced to mediate these effects is unknown.

[65] Attracted to the wound site by growth factors released by platelets and other cells, monocytes from the bloodstream enter the area through blood vessel walls.

[citation needed] Melanophages are a subset of tissue-resident macrophages able to absorb pigment, either native to the organism or exogenous (such as tattoos), from extracellular space.

In contrast to dendritic juncional melanocytes, which synthesize melanosomes and contain various stages of their development, the melanophages only accumulate phagocytosed melanin in lysosome-like phagosomes.

[citation needed] In order to minimize the possibility of becoming the host of an intracellular bacteria, macrophages have evolved defense mechanisms such as induction of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen intermediates,[85] which are toxic to microbes.

Recent evidence suggests that in response to the pulmonary infection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the peripheral macrophages matures into M1 phenotype.

[88] Adenovirus (most common cause of pink eye) can remain latent in a host macrophage, with continued viral shedding 6–18 months after initial infection.

[94][95] Inflammatory compounds, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha released by the macrophages activate the gene switch nuclear factor-kappa B. NF-κB then enters the nucleus of a tumor cell and turns on production of proteins that stop apoptosis and promote cell proliferation and inflammation.

[100][101][102] Additionally, subcapsular sinus macrophages in tumor-draining lymph nodes can suppress cancer progression by containing the spread of tumor-derived materials.

[103] Experimental studies indicate that macrophages can affect all therapeutic modalities, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

[112][113] Because macrophages can regulate tumor progression, therapeutic strategies to reduce the number of these cells, or to manipulate their phenotypes, are currently being tested in cancer patients.

[116] Similarly, studies identified macrophages genetically engineered to express chimeric antigen receptors as promising therapeutic approach to lowering tumor burden.

[118] The modulation of the inflammatory state of adipose tissue macrophages has therefore been considered a possible therapeutic target to treat obesity-related diseases.

[119] Although adipose tissue macrophages are subject to anti-inflammatory homeostatic control by sympathetic innervation, experiments using ADRB2 gene knockout mice indicate that this effect is indirectly exerted through the modulation of adipocyte function, and not through direct Beta-2 adrenergic receptor activation, suggesting that adrenergic stimulation of macrophages may be insufficient to impact adipose tissue inflammation or function in obesity.

[120] Within the fat (adipose) tissue of CCR2 deficient mice, there is an increased number of eosinophils, greater alternative macrophage activation, and a propensity towards type 2 cytokine expression.

In an obese individual some adipocytes burst and undergo necrotic death, which causes the residential M2 macrophages to switch to M1 phenotype.

[126] Additionally, a new study reveals macrophages limit iron access to bacteria by releasing extracellular vesicles, improving sepsis outcomes.

[130] Later on, Van Furth during the 1960s proposed the idea that circulating blood monocytes in adults allowed for the origin of all tissue macrophages.

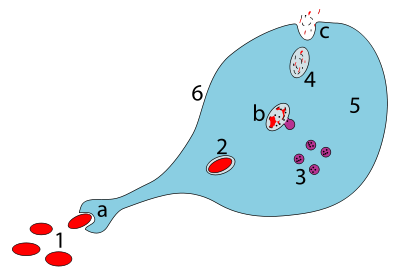

a. Ingestion through phagocytosis, a phagosome is formed

b. The fusion of lysosomes with the phagosome creates a phagolysosome ; the pathogen is broken down by enzymes

c. Waste material is expelled or assimilated (the latter not pictured)

Parts:

1. Pathogens

2. Phagosome

3. Lysosomes

4. Waste material

5. Cytoplasm

6. Cell membrane