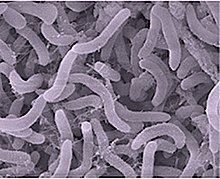

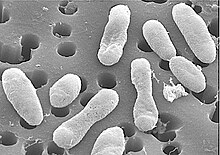

Marine prokaryotes

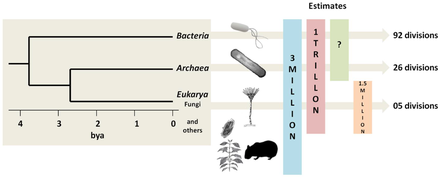

[9][10][11] The earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates from at least 3.5 billion years ago,[12][13] during the Eoarchean Era after a geological crust started to solidify following the earlier molten Hadean Eon.

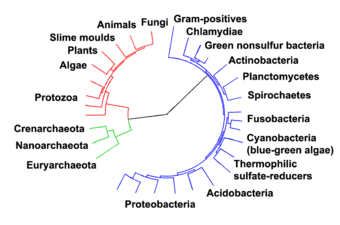

The history of life was that of the unicellular prokaryotes and eukaryotes until about 610 million years ago when multicellular organisms began to appear in the oceans in the Ediacaran period.

[17][26] The evolution of multicellularity occurred in multiple independent events, in organisms as diverse as sponges, brown algae, cyanobacteria, slime moulds and myxobacteria.

[28] Soon after the emergence of these first multicellular organisms, a remarkable amount of biological diversity appeared over a span of about 10 million years, in an event called the Cambrian explosion.

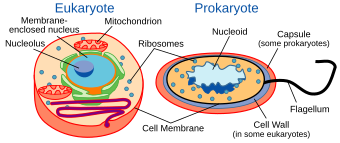

The division of life forms between prokaryotes and eukaryotes was firmly established by the microbiologists Roger Stanier and C. B. van Niel in their 1962 paper, The concept of a bacterium.

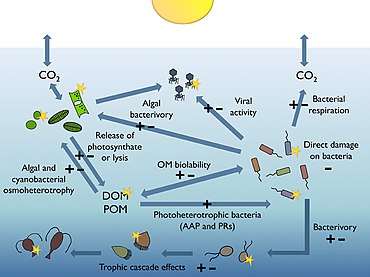

[56]: 5 They infect and destroy bacteria and archaea in aquatic microbial communities, and are the most important mechanism of recycling carbon in the marine environment.

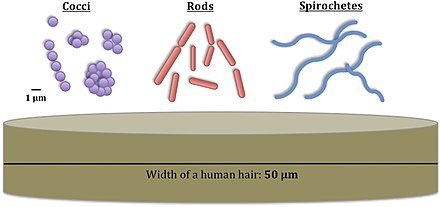

Bacteria inhabit soil, water, acidic hot springs, radioactive waste,[61] and the deep portions of Earth's crust.

Because oxygen was toxic to most life on Earth at the time, this led to the near-extinction of oxygen-intolerant organisms, a dramatic change which redirected the evolution of the major animal and plant species.

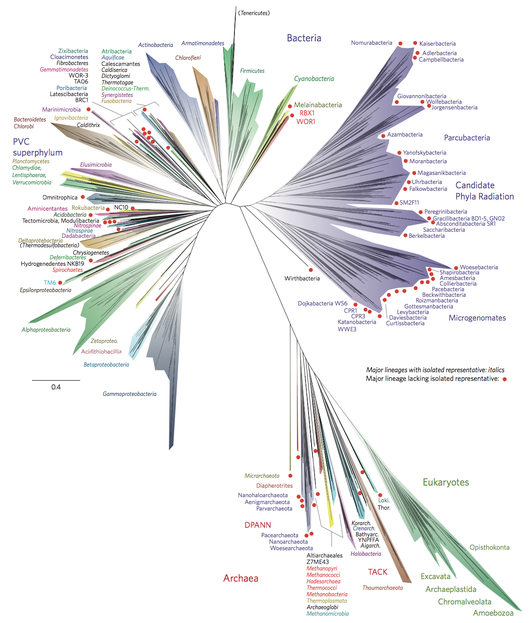

[94] Despite this morphological similarity to bacteria, archaea possess genes and several metabolic pathways that are more closely related to those of eukaryotes, notably the enzymes involved in transcription and translation.

Archaea use more energy sources than eukaryotes: these range from organic compounds, such as sugars, to ammonia, metal ions or even hydrogen gas.

Archaea reproduce asexually by binary fission, fragmentation, or budding; unlike bacteria and eukaryotes, no known species forms spores.

Thermoproteota (also called Crenarchaeota or eocytes) are a phylum of archaea thought to be very abundant in marine environments and one of the main contributors to the fixation of carbon.

This enables marine prokaryotes to thrive as extremophiles in harsh environments as cold as the ice surface of Antarctica, studied in cryobiology, as hot as undersea hydrothermal vents, or in high saline conditions as (halophiles).

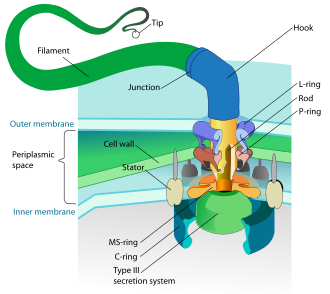

Magnetotactic bacteria utilize Earth's magnetic field to facilitate downward swimming into the oxic–anoxic interface, which is the most favorable place for their persistence and proliferation, in chemically stratified sediments or water columns.

[138] Depending on their latitude and whether the bacteria are north or south of the equator, the Earth's magnetic field has one of the two possible polarities, and a direction that points with varying angles into the ocean depths, and away from the generally more oxygen rich surface.

However, despite extensive research in recent years, it has yet to be established whether magnetotactic bacteria steer their flagellar motors in response to their alignment in magnetic fields.

Natural selection has fine tuned the structure of the gas vesicle to maximise its resistance to buckling, including an external strengthening protein, GvpC, rather like the green thread in a braided hosepipe.

[125] These bacteria may be free living (such as Vibrio harveyi) or in symbiosis with animals such as the Hawaiian bobtail squid (Aliivibrio fischeri) or terrestrial nematodes (Photorhabdus luminescens).

[148] Another possible reason bacteria use luminescence reaction is for quorum sensing, an ability to regulate gene expression in response to bacterial cell density.

The significance of chlorophyll in converting light energy has been written about for decades, but phototrophy based on retinal pigments is just beginning to be studied.

[153] In 2000 a team of microbiologists led by Edward DeLong made a crucial discovery in the understanding of the marine carbon and energy cycles.

[157] The archaeal-like rhodopsins have subsequently been found among different taxa, protists as well as in bacteria and archaea, though they are rare in complex multicellular organisms.

"The findings break from the traditional interpretation of marine ecology found in textbooks, which states that nearly all sunlight in the ocean is captured by chlorophyll in algae.

They have what appear to be hairy backs, but these "hairs" are actually colonies of bacteria such as Nautilia profundicola, which are thought to afford the worm some degree of insulation.

The symbiotic bacteria also allow the worm to use hydrogen and carbon monoxide as energy sources, and to metabolise organic compounds like malate and acetate.

The coral can live with and without zooxanthellae (algal symbionts), making it an ideal model organism to study microbial community interactions associated with symbiotic state.

[172][173] Heterotrophic bacterioplankton are main consumers of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in pelagic marine food webs, including the sunlit upper layers of the ocean.

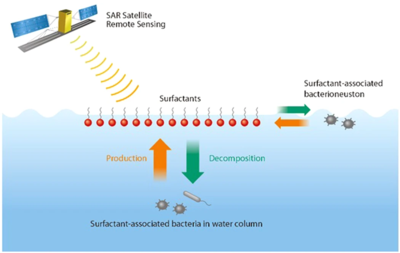

Having the ability to detect these "invisible" surfactant-associated bacteria using synthetic aperture radar has immense benefits in all-weather conditions, regardless of cloud, fog, or daylight.

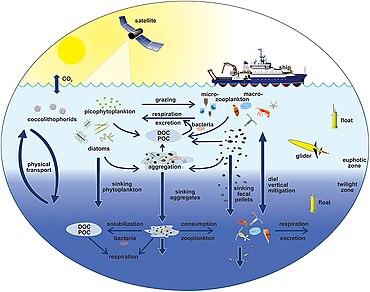

[174] The diagram on the right shows links among the ocean's biological pump and the pelagic food web and the ability to sample these components remotely from ships, satellites, and autonomous vehicles.

[182] In the carbon cycle, methanogen archaea remove hydrogen and play an important role in the decay of organic matter by the populations of microorganisms that act as decomposers in anaerobic ecosystems, such as sediments and marshes.

interact with bacteria to acquire iron from dust

b. Trichodesmium can establish massive blooms in nutrient poor ocean regions with high dust deposition, partly due to their unique ability to capture dust, center it, and subsequently dissolve it.

c. Proposed dust-bound Fe acquisition pathway: Bacteria residing within the colonies produce siderophores (c-I) that react with the dust particles in the colony core and generate dissolved Fe (c-II). This dissolved Fe, complexed by siderophores, is then acquired by both Trichodesmium and its resident bacteria (c-III), resulting in a mutual benefit to both partners of the consortium . [ 82 ]

(2) it changes its configuration so a proton is expelled from the cell

(3) the chemical potential causes the proton to flow back to the cell

(4) thus generating energy

(5) in the form of adenosine triphosphate . [ 152 ]