Marine microorganisms

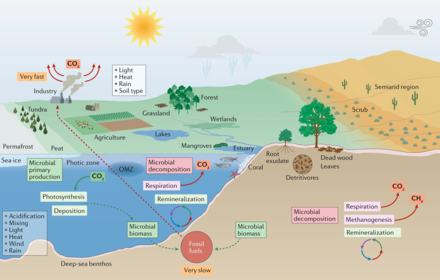

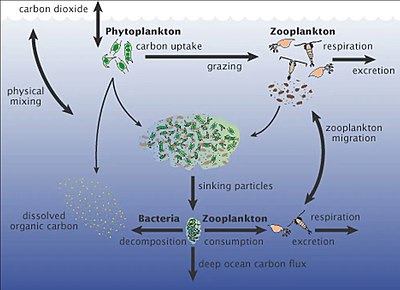

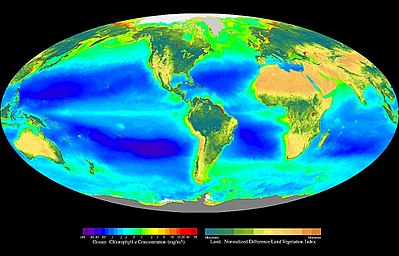

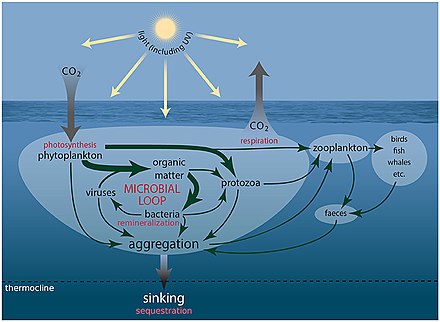

[9] However marine microorganisms recycle the major chemical elements, both producing and consuming about half of all organic matter generated on the planet every year.

In July 2016, scientists reported identifying a set of 355 genes from the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all life on the planet, including the marine microorganisms.

[8] Viruses Bacteria Archaea Protists Microfungi Microanimals While recent technological developments and scientific discoveries have been substantial, we still lack a major understanding at all levels of the basic ecological questions in relation to the microorganisms in our seas and oceans.

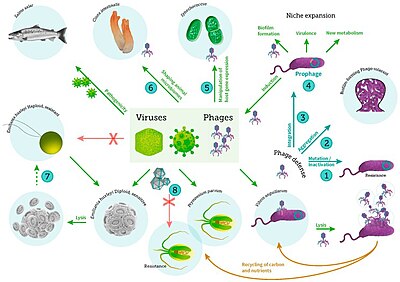

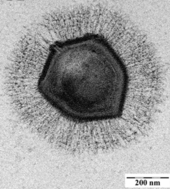

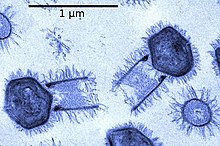

[38] They are a common and diverse group of viruses and are the most abundant biological entity in marine environments, because their hosts, bacteria, are typically the numerically dominant cellular life in the sea.

[38] However, as a result of more recent research, non-tailed viruses appear to be dominant in multiple depths and oceanic regions, followed by the Caudovirales families of myoviruses, podoviruses, and siphoviruses.

[32] It is thought that viruses played a central role in the early evolution, before the diversification of bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes, at the time of the last universal common ancestor of life on Earth.

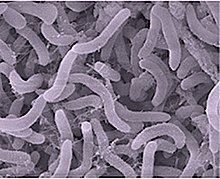

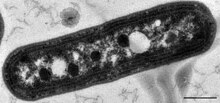

[81] Despite this morphological similarity to bacteria, archaea possess genes and several metabolic pathways that are more closely related to those of eukaryotes, notably the enzymes involved in transcription and translation.

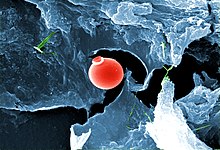

[89][90] Studies have shown high protist diversity exists in oceans, deep sea-vents and river sediments, suggesting a large number of eukaryotic microbial communities have yet to be discovered.

Some marine nematodes and rotifers are also too small to be recognised with the naked eye, as are many loricifera, including the recently discovered anaerobic species that spend their lives in an anoxic environment.

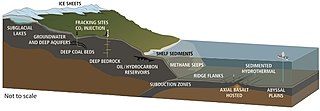

Some marine primary producers are specialised bacteria and archaea which are chemotrophs, making their own food by gathering around hydrothermal vents and cold seeps and using chemosynthesis.

Because oxygen was toxic to most life on Earth at the time, this led to the near-extinction of oxygen-intolerant organisms, a dramatic change which redirected the evolution of the major animal and plant species.

Selective breeding in aquariums to produce hardier strains resulted in an accidental release into the Mediterranean where it has become an invasive species known colloquially as killer algae.

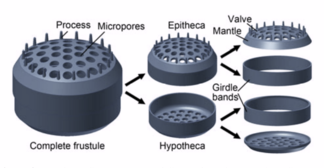

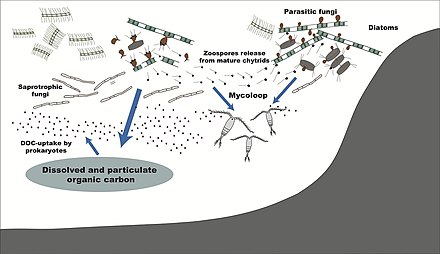

[157] Phytoplankton include cyanobacteria (above), diatoms, various other types of algae (red, green, brown, and yellow-green), dinoflagellates, euglenoids, coccolithophorids, cryptomonads, chlorophytes, prasinophytes, and silicoflagellates.

"The findings break from the traditional interpretation of marine ecology found in textbooks, which states that nearly all sunlight in the ocean is captured by chlorophyll in algae.

Many protozoans (single-celled protists that prey on other microscopic life) are zooplankton, including zooflagellates, foraminiferans, radiolarians, some dinoflagellates and marine microanimals.

A mixotroph is an organism that can use a mix of different sources of energy and carbon, instead of having a single trophic mode on the continuum from complete autotrophy at one end to heterotrophy at the other.

The luminescence, sometimes called the phosphorescence of the sea, occurs as brief (0.1 sec) blue flashes or sparks when individual scintillons are stimulated, usually by mechanical disturbances from, for example, a boat or a swimmer or surf.

In 2020 it was reported that researchers have examined the chemical composition of thousands of samples of these benthic forams and used their findings to build the most detailed climate record of Earth ever.

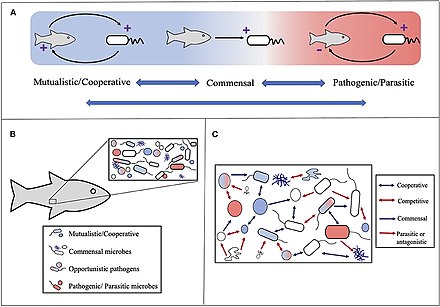

[227][228][229] The concept of the holobiont was initially defined by Dr. Lynn Margulis in her 1991 book Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation as an assemblage of a host and the many other species living in or around it, which together form a discrete ecological unit.

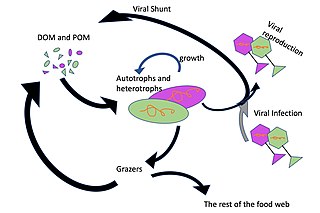

[244] Viral shunting helps maintain diversity within the microbial ecosystem by preventing a single species of marine microbe from dominating the micro-environment.

[256] As their infections are often fatal, they constitute a significant source of mortality and thus have widespread influence on biological oceanographic processes, evolution and biogeochemical cycling within the ocean.

[259] Like in other marine environments, deep-sea hydrothermal viruses affect abundance and diversity of prokaryotes and therefore impact microbial biogeochemical cycling by lysing their hosts to replicate.

[260] However, in contrast to their role as a source of mortality and population control, viruses have also been postulated to enhance survival of prokaryotes in extreme environments, acting as reservoirs of genetic information.

Lower down, these are not available, so they make use of "edibles" (electron donors) such as hydrogen released from rocks by various chemical processes, methane, reduced sulfur compounds and ammonium.

The microorganisms were found in organically poor sediments 68.9 metres (226 feet) below the seafloor in the South Pacific Gyre (SPG), "the deadest spot in the ocean".

This resulted in erroneous, distorted and confused classification, an example of which, noted Carl Woese, is Pseudomonas whose etymology ironically matched its taxonomy, namely "false unit".

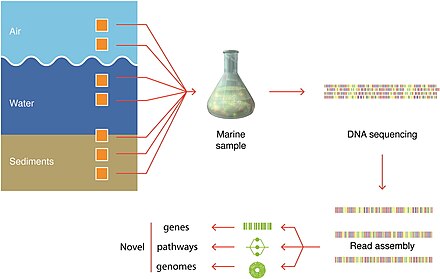

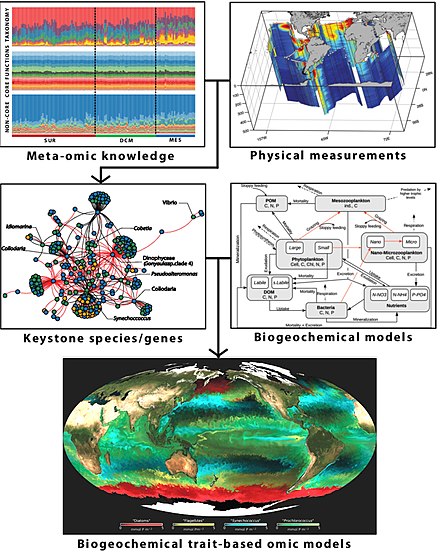

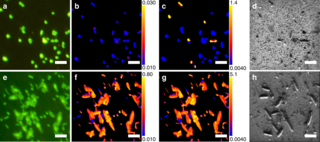

[283] These new possibilities have revolutionized microbial ecology, because the analysis of genomes and metagenomes in a high-throughput manner provides efficient methods for addressing the functional potential of individual microorganisms as well as of whole communities in their natural habitats.

[6] Microorganisms have key roles in carbon and nutrient cycling, animal (including human) and plant health, agriculture and the global food web.

Unless we appreciate the importance of microbial processes, we fundamentally limit our understanding of Earth's biosphere and response to climate change and thus jeopardize efforts to create an environmentally sustainable future.

Over eons, the photosynthesis of marine microorganisms generated by oxygen has helped shape the chemical environment in the evolution of plants, animals and many other life forms.

including viral infection of bacteria, phytoplankton and fish [ 30 ]

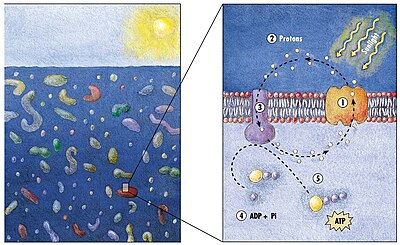

(2) it changes its configuration so a proton is expelled from the cell

(3) the chemical potential causes the proton to flow back to the cell

(4) thus generating energy

(5) in the form of adenosine triphosphate . [ 165 ]

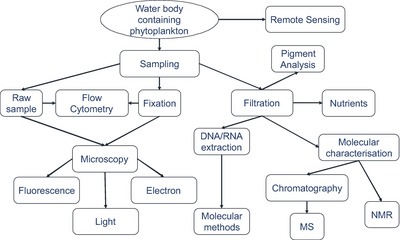

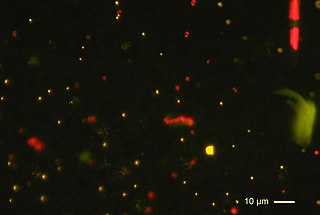

The blue background indicates the filtered volume required to obtain sufficient organism numbers for analysis.

Actual volumes from which organisms are sampled are always recorded. [ 277 ]