Military history of Mexico

The Mexican army that emerged in the wake of the French Intervention was young and battle tested, not part of the military tradition dating to the colonial and early independence eras.

[6] As early as Teotihuacan and Monte Albán, the first Mesoamerican states, there is evidence of local conquests of defensive walls around urban cores and conflicts resulting in large-scale sacrifice of warriors.

The Mayan conflict also included vassal states in the Petén Basin such as Copan, Dos Pilas, Naranjo, Sacul, Quiriguá, and briefly Yaxchilan had a role in initiating the first war.

Historical accounts such as that of Juan Bautista de Pomar state that small pieces of meat were offered as gifts to important people in exchange for presents and slaves, but it was rarely eaten, since they considered it had no value; instead it was replaced by turkey, or just thrown away.

An exception was the 1541 Mixtón war, where an uprising in what is now Jalisco was suppressed by armed Spaniards and their loyal Tlaxcalan allies led by the highest Spanish administrator, the viceroy, Don Antonio de Mendoza.

The 1762 British capture of Havana, Cuba and Manila, the Philippines in the Seven Years' War, prompted the Spanish crown to protect its colony of Mexico by establishing a standing military.

[15] In the eighteenth century, the Bourbon regime had introduced practices and reforms that systematically excluded elite American-born Spaniards from holding high civil or ecclesiastical office.

The Criollos, or American-born rather than Spaniards born in Spain (Peninsulares) had since the eighteen-century Bourbon reforms been passed over for high posts in the civil and ecclesiastical structures; mixed-race castas and indigenous peoples were legally lower in standing with unequal access to justice and usually lived in dire poverty.

The Grito de Dolores that had denounced bad government touched off a massive uprising by mixed-race castas and indigenous tens of thousands of unorganized followers of Hidalgo.

Royalist army officer Agustín de Iturbide drafted the Plan of Iguala, calling for political independence, a constitutional monarchy, equality, and Catholicism as its core principles.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, ended the war and gave the USA undisputed control of Texas as well as California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Wyoming.

The Mexican government was in a rare position of being cash rich from payment by the United States under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo for the territory taken in the Mexican–American War, and accepted Yucatán's offer.

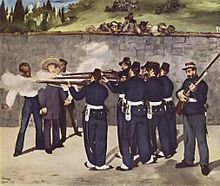

This period was the only one in the nineteenth century with civilian control of the government, but it was not a peaceful era, with a civil war and the foreign invasion of the French and monarchy supported by Mexico's Conservatives, followed by the restoration of the Liberal Republic.

Although Carranza held the capital, local revolutionary generals controlled a number of regions of Mexico, such as Saturnino Cedillo in San Luis Potosí, along with bands of bandits.

[24] Mexico entered a period of what has been called "predatory militarism", where revolutionary strongmen were "venal, cruel, and corrupt", taking on the worst characteristics of the ousted Federal Army.

The huge task of forging a regime that held effective power meant bringing the revolutionary armies of the Constitutionalist coalition and their officers under the control of the civilian central government.

Many generals were of modest social backgrounds, as opposed to Carranza, a wealthy landowner and professional politician, and the military men were ideologically more radical concerning the changes they envisioned for post-revolutionary Mexico.

Carranza was attempting to consolidate his own regime and gain central control over revolutionary armies, so he held fast to Mexican neutrality in the larger conflict rather than risk an escalation with the U.S.

Revolutionary generals in Sonora, Adolfo de la Huerta, Plutarco Elías Calles, and Alvaro Obregón promulgated the Plan of Agua Prieta and rose up against Carranza.

De la Huerta's most successful action was to grant amnesty to Pancho Villa, who had remained a threat, purchasing a landed estate for him in exchange for his laying down arms and generous cash payments.

From a humble indigenous background, Amaro distinguished himself on the battlefield during the Revolution and then picked the right side in the coup against Carranza and in the failed De la Huerta rebellion.

General Abelardo Rodríguez, who became president of Mexico during the Maximato, created a vast fortune as an entrepreneur in border towns, owning race tracks, casinos, and brothels and then diversified into real estate and financial services.

Calles could not directly serve as president, but he brokered a solution to presidential succession by founding the Partido Nacional Revolucionario (PNR), the precursor of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

Cárdenas resigned his post as Minister of War and ran for the presidency with the support of Saturnino Cedillo, the radical strongman of the state of San Luis Potosí and other generals.

[50] One recent event in the military history of Mexico is that of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, which is an armed rebel group that claims to work to promote the rights of the country's indigenous peoples.

The federal government instead pursued a policy of low-intensity warfare with para-military groups in an attempt to control the rebellion, while the Zapatistas developed a media campaign through numerous newspaper comunicados and over time a set of six "Declarations of the Lacandonian Jungle", with no further military or terrorist actions on their part.

[51] With the release of “Historical Report to the Mexican Society” Mexico accepted full responsibility for starting a dirty war against leftist guerrillas, university students, and activists.

[53] It all began in 1960, when Echeverría wanted to take over the Guerrero region with his "dirty war tactics" that involved his desire to tamp down military dissatisfaction by giving the army and the security forces the green light to attack the left.

An early version of the report was leaked in February to the Mexican press against the wishes of Fox and Carrillo, who felt it was biased against the military and left out important facts.

On March 1, 2019, the President of Mexico, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, released the official archives of the Federal Security Directorate which showed how'd intelligence agencies targeted activists and opposition groups during the country's "Dirty War."