Liquid crystal

In 1888, Austrian botanical physiologist Friedrich Reinitzer, working at the Karl-Ferdinands-Universität, examined the physico-chemical properties of various derivatives of cholesterol which now belong to the class of materials known as cholesteric liquid crystals.

The research was continued by Lehmann, who realized that he had encountered a new phenomenon and was in a position to investigate it: In his postdoctoral years he had acquired expertise in crystallography and microscopy.

[3] Lehmann's work was continued and significantly expanded by the German chemist Daniel Vorländer, who from the beginning of the 20th century until he retired in 1935, had synthesized most of the liquid crystals known.

This conference marked the beginning of a worldwide effort to perform research in this field, which soon led to the development of practical applications for these unique materials.

This led his colleague George H. Heilmeier to perform research on a liquid crystal-based flat panel display to replace the cathode ray vacuum tube used in televisions.

But the para-azoxyanisole that Williams and Heilmeier used exhibits the nematic liquid crystal state only above 116 °C, which made it impractical to use in a commercial display product.

This technique of mixing nematic compounds to obtain wide operating temperature range eventually became the industry standard and is still used to tailor materials to meet specific applications.

In 1969, Hans Keller succeeded in synthesizing a substance that had a nematic phase at room temperature, N-(4-methoxybenzylidene)-4-butylaniline (MBBA), which is one of the most popular subjects of liquid crystal research.

[11] The next step to commercialization of liquid-crystal displays was the synthesis of further chemically stable substances (cyanobiphenyls) with low melting temperatures by George Gray.

[12] That work with Ken Harrison and the UK MOD (RRE Malvern), in 1973, led to design of new materials resulting in rapid adoption of small area LCDs within electronic products.

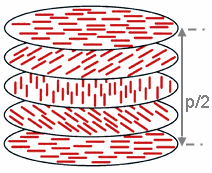

In a nematic phase, calamitic organic molecules lack a crystalline positional order, but do self-align with their long axes roughly parallel.

The molecules are free to flow and their center of mass positions are randomly distributed as in a liquid, but their orientation is constrained to form a long-range directional order.

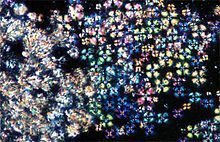

[39][40] Although blue phases are of interest for fast light modulators or tunable photonic crystals, they exist in a very narrow temperature range, usually less than a few kelvins.

[47] In contrast to thermotropic liquid crystals, these lyotropics have another degree of freedom of concentration that enables them to induce a variety of different phases.

The addition of long chain soap-like molecules leads to a series of new phases that show a variety of liquid crystalline behavior both as a function of the inorganic-organic composition ratio and of temperature.

[55] The existence of a true nematic phase in the case of the smectite clays family was raised by Langmuir in 1938,[56] but remained an open question for a very long time and was only confirmed recently.

[57][58] With the rapid development of nanosciences, and the synthesis of many new anisotropic nanoparticles, the number of such mineral liquid crystals is increasing quickly, with, for example, carbon nanotubes and graphene.

For example, injection of a flux of a liquid crystal between two close parallel plates (viscous fingering) causes orientation of the molecules to couple with the flow, with the resulting emergence of dendritic patterns.

[61] Microscopic theoretical treatment of fluid phases can become quite complicated, owing to the high material density, meaning that strong interactions, hard-core repulsions, and many-body correlations cannot be ignored.

To describe this anisotropic structure, a dimensionless unit vector n called the director, is introduced to represent the direction of preferred orientation of molecules in the neighborhood of any point.

This statistical theory, proposed by Alfred Saupe and Wilhelm Maier, includes contributions from an attractive intermolecular potential from an induced dipole moment between adjacent rod-like liquid crystal molecules.

[66][67][68] Maier-Saupe mean field theory is extended to high molecular weight liquid crystals by incorporating the bending stiffness of the molecules and using the method of path integrals in polymer science.

The first is simply the average of the second Legendre polynomial and the second order parameter is given by: The values zi, θi, and d are the position of the molecule, the angle between the molecular axis and director, and the layer spacing.

Consider the case in which liquid crystal molecules are aligned parallel to the surface and an electric field is applied perpendicular to the cell.

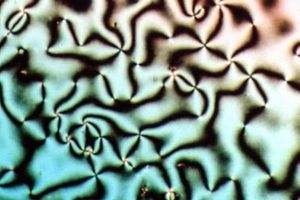

The occurrence of such a change from an aligned to a deformed state is called a Fréedericksz transition and can also be produced by the application of a magnetic field of sufficient strength.

The Fréedericksz transition is fundamental to the operation of many liquid crystal displays because the director orientation (and thus the properties) can be controlled easily by the application of a field.

Thus, liquid crystal sheets are often used in industry to look for hot spots, map heat flow, measure stress distribution patterns, and so on.

Liquid crystal in fluid form is used to detect electrically generated hot spots for failure analysis in the semiconductor industry.

As for projecting images or sensing objects, it may be expected to have the liquid crystal lens with aspheric distribution of optical path length across its aperture of interest.

[36][89] Polymer dispersed liquid crystal (PDLC) sheets and rolls are available as adhesive backed Smart film which can be applied to windows and electrically switched between transparent and opaque to provide privacy.