Rus' people

[5] The name Garðaríki was applied to the newly formed state of Kievan Rus',[6] and the ruling Norsemen along with local Finnic tribes gradually assimilated into the East Slavic population and came to speak a common language.

[8][9][12][13] The Finnish and Russian forms of the name have a final -s revealing an original compound where the first element was rōþ(r)s- (preceding a voiceless consonant, þ is pronounced like th in English thing).

[8] The prefix form rōþs- is found not only in Ruotsi and Rusʹ, but also in Old Norse róþsmenn and róþskarlar, both meaning "rowers",[13] and in the modern Swedish name for the people of Roslagen – rospiggar[14] which derives from ON *rōþsbyggiar ("inhabitants of Rōþin").

Two of them are roþ for rōþer /róðr, meaning "fleet levy", on the Håkan stone, and as i ruþi (translated as "dominion") on the lost Nibble stone, in the old Swedish heartland in the Mälaren Valley,[17][18] and the possible third one was identified by Erik Brate in the most widely accepted reading as roþ(r)slanti on the Piraeus Lion originally located in Athens, where a runic inscription was most likely carved by Swedish mercenaries serving in the Varangian Guard.

[14] Between the two compatible theories represented by róðr or Róðinn, modern scholarship leans towards the former because at the time, the region covered by the latter term, Roslagen, remained sparsely populated and lacked the demographic strength necessary to stand out compared to the adjacent Swedish heartland of the Mälaren Valley.

[31][32] At that point, the new term Varangian was increasingly preferred to name the Scandinavians,[33] probably mostly from what is currently Sweden,[34] plying the river routes between the Baltic and the Black and Caspian Seas.

[35][36][37][38] Relatively few of the rune stones Varangians left in their native Sweden tell of their journeys abroad,[39] to such places as what is today Russia, Ukraine, Belarus,[40] Greece, and Italy.

[44] The latter town, Novgorod, was another centre of the same culture but founded in different surroundings, where some old local traditions moulded this commercial city into the capital of a powerful oligarchic trading republic of a kind otherwise unknown in this part of Europe.

[4] This was the territory that most probably was originally called by the Norsemen Gardar, a name that long after the Viking Age acquired a much broader meaning and became Garðaríki, a denomination for the entire state.

[48] The prehistory of the first territory of Rus' has been sought in the developments around the early-8th century, when Staraja Ladoga was founded as a manufacturing centre and to conduct trade, serving the operations of Scandinavian hunters and dealers in furs obtained in the north-eastern forest zone of Eastern Europe.

These elements, which were current in 10th-century Scandinavia, appear at various places in the form of collections of many types of metal ornaments, mainly female but male also, such as weapons, decorated parts of horse bridles, and diverse objects embellished in contemporaneous Norse art styles.

[61][62] The Fagerlöt runestone gives a hint of the Old Norse spoken in Kievan Rus', as folksgrimʀ may have been the title that the commander had in the retinue of Yaroslav I the Wise in Novgorod.

[67] The earliest Slavonic-language narrative account of Rus' history is the Primary Chronicle, compiled and adapted from a wide range of sources in Kiev at the start of the 13th century.

[69] The Chronicle presents the following origin myth for the arrival of Rus' in the region of Novgorod: the Rus'/Varangians 'imposed tribute upon the Chuds, the Slavs, the Merians, the Ves', and the Krivichians' (a variety of Slavic and Finnic peoples).

[85] Arabic sources portray Rus' people fairly clearly as a raiding and trading diaspora, or as mercenaries, under the Volga Bulghars or the Khazars, rather than taking a role in state formation.

[89] In his treatise De Administrando Imperio, Constantine VII describes the Rhos as the neighbours of Pechenegs who buy from the latter cows, horses, and sheep "because none of these animals may be found in Rhosia"; his description represents the Rus' as a warlike northern tribe.

Once Louis enquired the reason of their arrival (in the Latin text, ... Quorum adventus causam imperator diligentius investigans, ...), he learnt that they were Swedes (eos gentis esse Sueonum; verbatim, their nation is Sveoni).

Usually, the only non-archaeological claim to rapid assimilation is the appearance of three Slavic names in the princely family, i.e. Svjatoslav, Predslava, and Volodislav, for the first time in the treaty with Byzantium of 944.

[113] Melnikova comments that the disappearance of Norse funeral traditions c. 1000, is better explained with Christianisation and the introduction of Christian burial rites, a view described with some reservations by archaeologist Przemysław Urbańczyk of the Institute of Archeology and Ethnology at the Polish Academy of Sciences.

She also notes that no systematic studies of the various elements that manifest ethnic identity in relation to the Rus' has been done to support the theory of rapid assimilation, in spite of the fact that "[t]he most important indications of ethno-cultural self-identification are language and literacy.

The other members of the family have Norse names, i.e. Olga (Helga), Akun (Hákon), Sfanda (Svanhildr), Uleb (Óleifr), Turd (Þórðr), Arfast (Arnfastr), and Sfir'ka (Sverkir).

[115] The linguist and literary theorist Roman Jakobson held a contrasting opinion, writing that Bojan, active at the court of Yaroslav the Wise, and some of whose poetry may be preserved in the epic poem The Tale of Igor's Campaign, or Slovo, in Old East Slavic, may have heard Scandinavian songs and conversations from visitors as late as 1110 (about the time his own work was done), and that even later, at the court of Mstislav (Haraldr), there must have been many opportunities to hear them.

Scholarly consensus holds as well that the author of the national epic, Slovo, writing in the late 12th century, was not composing in a milieu where there was still a flourishing school of poetry in the Old Norse language.

[7] Sten, the man from Mikula, could be a visitor from Sweden or Swedish-speaking Finland, but the other letters suggest people who had Norse names but were otherwise part of the local culture.

According to the most critical and conservative analysis, commonly used ON words include knut ("knout"), seledka ("herring"), šelk ("silk"), and jaščik ("box"), whereas varjag ("Varangian"), stjag ("flag") and vitjaz' ("hero", from viking) mostly belong to historical novels.

[131] Northern Russia and adjacent Finnic lands had become a profitable meeting ground for peoples of diverse origins, especially for the trade of furs, and attracted by the presence of oriental silver from the mid-8th century AD.

[133] In the 21st century, analyses of the rapidly growing range of archaeological evidence further noted that high-status 9th- to 10th-century burials of both men and women in the vicinity of the Upper Volga exhibit material culture largely consistent with that of Scandinavia (though this is less the case away from the river, or further downstream).

[134][page needed][135] There is uncertainty as to how small the Scandinavian migration to Rus' was, but some recent archaeological work has argued for a substantial number of 'free peasants' settling in the upper Volga region.

[136][137] The quantity of archaeological evidence for the regions where the Rus' people were active grew steadily through the 20th century, and beyond, and the end of the Cold War made the full range of material increasingly accessible to researchers.

[134][page needed][135] The distribution of coinage, including the early 9th-century Peterhof Hoard, has provided important ways to trace the flow and quantity of trade in areas where Rus' were active, and even, through graffiti on the coins, the languages spoken by traders.

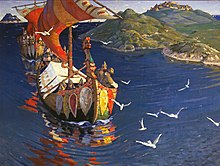

Henryk Siemiradzki (1883)