33rd Alabama Infantry Regiment

During a fierce rainstorm one night, a Federal ship endeavoring to resupply Ft. Pickens encountered difficulties and jettisoned some of its cargo (described as "many barrels of vinegar, boxes of crackers and other things"[7]); sentinels from Co's B and I mistook these floating crates for an amphibious assault force approaching their position, and fired on them before realizing their error.

[10] During this time, the men of the 33rd discarded many items that they now considered non-essential, burdened down as they were on their frequent marches: "hammers, pillows, towels, books, bedclothing, clothing, big knives, tinware, sheepskins, bear skins and other paraphernalia.

[11] In concert with the rest of the army, the 33rd left Corinth at the end of July and travelled by train from Tupelo, Mississippi, to Meridian; thence to Mobile, Alabama, and Montgomery, then on to Atlanta, Georgia, and Dalton before arriving at Tyner's Station, just east of Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Emboldened by recent successes achieved by Confederate raiders under Colonel John Hunt Morgan and seeking to divert Federal attention from the strategically important towns of Chattanooga and Vicksburg, Mississippi, General Bragg decided to invade Kentucky, a slave state that had remained loyal to the Union—but which still contained a large pro-Confederate minority.

A battle commenced on the morning of October 8, with the 33rd taking little part until late afternoon, when Bragg called for fresh troops to launch an attack on Dixville Crossroads, held by the 34th Federal Brigade under Colonel George Webster.

[19] Private Matthews describes the action in these words: We got to Perryville October 7th, I think around 10:00 AM, passed through the town and bivouacked to the north or left of the pike, obtaining water under a deep lime sink, then moved by the right flank in column and halted in line on a ridge.

From here he continued his retreat to Knoxville, Tennessee, where the army drew supplies described as: "flour, corn meal, bacon, fresh beef, rice, salt and the first soap that we had drawn in two months," together with new uniforms and shoes.

Private Matthews reports that the 33rd Alabama was tasked to serve as a rear guard for their brigade along the line of march, occasionally skirmishing with pursuing Federal forces while contending with muddy roads during the final portion of their journey.

We ... fished in creeks or rivers or went in bathing, and some frequently attended religious services ... Green bandsmen near us making discordant noise on their tin horns caused some of the boys to swear, though we liked the music after they had learned to play.

Hearing the Federals open fire on the 24th, the 33rd Alabama cooked three days' rations of flour, beef, bacon and corn meal, then marched back to the main army at Tullahoma,[43] which was evacuated around June 30.

An abortive assault launched by Cleyburne's and Hindman's divisions at Davis's Cross Roads allowed the Federals to escape to safety, so Bragg now turned north, where Rosecran's main force was rapidly concentrating at Lee and Gordon's Mill along Chickamauga Creek.

With the Federals putting up a terrific fight and showing no disposition to give way, Bragg ordered the 33rd Alabama and the rest of Cleburne's division (which had been on the left side of his army up to this point)[49] to move north to the Youngblood Farm, near the far right flank.

[60] Several men from the regiment had failed to remove their ramrods from their rifles as they fired them during the engagement; according to Matthews, these were stuck in trees as high as twenty feet above the ground; others were buried partway in the soil.

At 7:25 that morning, as his men were eating breakfast, Cleburne received orders from Polk to attack the Federal line in a new location known as Kelly Field, in conjunction with troops of Brigadier General John C. Breckinridge, a former Vice President of the United States who had sided with the South.

Completely bereft of support from either side, the 33rd continued to advance, ultimately achieving something no other Confederate regiment in that sector managed to do: it crossed the La Fayette Road, General Bragg's main objective.

"[70] Following the debacle at Chickamauga and his subsequent failure to prevent the routed Union forces from escaping to Chattanooga, Bragg placed that city under siege after hearing that his foes had just six days of food remaining.

Fresh from his victory at Vicksburg, Grant had been ordered to take command of all Federal forces in the region; his first action upon arriving was to remove Rosecrans and replace him with George Thomas, who had saved the Union army at Chickamauga.

He writes that those who died here were buried nearby; the regiment accompanied them to their final resting place "with arms [rifles] reversed, and sounded taps; however, [we] did not always fire blank cartridges from our guns, for fear of exciting other sick men in camp.

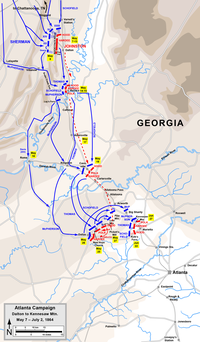

[94] A new flag was presented to the regiment with the words: "Perryville", "Murfreesboro", "Chickamauga" and "Ringgold Gap" embroidered on it, together with an oval-shaped disc in the center containing "33 ALA."[95] With the Federals having retreated temporarily, life at Dalton returned to normal—at least for the time being.

[99] At Resaca the 33rd Alabama was deployed with the rest of Hardee's Corps along Camp Creek, northwest of town; a series of Federal attacks on their lines were largely repulsed, until Sherman was able to flank Johnston and force him to retreat yet again.

After a clash at New Hope Church stopped the Federal advance, both sides rushed additional troops into the area; among them was Cleyburne's Division, which deployed on the far right flank of the Southern army in densely wooded terrain with Lowrey's Brigade (including the 33rd Alabama) in reserve on its left.

[114] Newton attacked the sector held by the 33rd, which lay across a shallow creek situated in a valley about twenty feet deep that gave way to sloping ground, all of which was densely forested and covered with thick underbrush that made a proper pre-attack reconnaissance impossible.

[122] With no means of washing their clothes, the men suffered from insect infestations; their agony was compounded by a nearby Federal gun that managed to draw a transverse bead on their trench, doing considerable damage until Confederate counter-battery fire finally silenced it.

[122] They were quickly ambushed by dismounted Union cavalry commanded by Hugh Judson Kilpatrick and armed with Spencer Repeating Rifles; the brigade managed to drive them back, but were soon stopped by other Federal troops and returned to their lines.

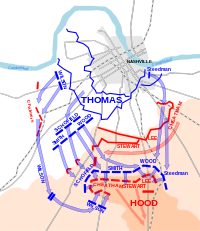

[134] Determined to stop Schofield from uniting with Thomas' main force at Nashville, Hood resolved to attack him head-on at Franklin, even though the Federals were now behind formidable fortifications (built for a previous battle fought there the year before).

[136] Moving through savage cannon fire toward the Carter House Cotton Gin across the field, the 33rd halted briefly with their sister regiments to fix bayonets, having been ordered not to shoot until they reached the Federal trenches.

[151] This section of the front was hit late in the day by a three-brigade attack led by Federal Brigadier General John McArthur, which smashed through the poorly placed defenses and rolled up Hood's line from west to east as additional Union forces joined the assault.

[154] On the way to Selma the following day, their train derailed in an eerie repeat of the episode in late 1862; several men from Companies B and G were sitting on top of the cars, and were injured when their boxcars left the tracks.

[35] Writing about knapsacks, canteens and other gear issued during their initial deployment to Ft. McRee, Matthews described: An oilcloth haversack suspended by a leather strap over our right shoulder, and hanging loose at our left side.

A regimental teamster was assigned to draw rations daily from the nearest railhead; in May 1864 these consisted of one pound of unbolted corn per man per day, or the same weight of flour made of wheat and cowpeas ground together.