Battle of Gettysburg

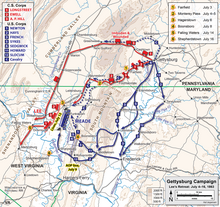

[fn 1][16] After his success at Chancellorsville in Virginia in May 1863, Lee led his Confederate forces through Shenandoah Valley to begin the Gettysburg Campaign, his second attempted invasion of the North.

Two large Confederate corps assaulted them from the northwest and north, however, collapsing the hastily developed Union lines, leading them to retreat through the streets of Gettysburg to the hills just south of the city.

In the late afternoon, Lee launched a heavy assault on the Union's left flank, leading to fierce fighting at Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, Devil's Den, and the Peach Orchard.

[12][13] On June 26, elements of Major General Jubal Early's division of Ewell's corps occupied the town of Gettysburg after chasing off newly raised 26th Pennsylvania emergency militia in a series of minor skirmishes.

[30] In a dispute over the use of the forces defending the Harpers Ferry garrison, Hooker offered his resignation, and Abraham Lincoln and General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck, who were looking for an excuse to rid themselves of him, immediately accepted.

[41] North of the pike, Davis gained a temporary success against Brigadier General Lysander Cutler's brigade but was repelled with heavy losses in an action around an unfinished railroad bed cut in the ridge.

Hill added Major General William Dorsey Pender's division to the assault, and the I Corps was driven back through the grounds of the Lutheran Seminary and Gettysburg streets.

Ewell, who had previously served under Stonewall Jackson, a general well known for issuing peremptory orders, determined such an assault was not practicable and, thus, did not attempt it; this decision is considered by historians to be a great missed opportunity.

McLaws, coming in on Hood's left, drove multiple attacks into the thinly stretched III Corps in the Wheatfield and overwhelmed them in Sherfy's Peach Orchard.

Anderson's division, coming from McLaws's left and starting forward around 6 p.m., reached the crest of Cemetery Ridge, but could not hold the position in the face of counterattacks from the II Corps, including an almost suicidal bayonet charge by the 1st Minnesota regiment against a Confederate brigade, ordered in desperation by Hancock to buy time for reinforcements to arrive.

[72] As fighting raged in the Wheatfield and Devil's Den, Colonel Strong Vincent of V Corps had a precarious hold on Little Round Top, an important hill at the extreme left of the Union line.

Meade's chief engineer, Brigadier General Gouverneur K. Warren, had realized the importance of this position, and dispatched Vincent's brigade, an artillery battery, and the 140th New York to occupy Little Round Top mere minutes before Hood's troops arrived.

[75] Early was similarly unprepared when he ordered Harry T. Hays's and Isaac E. Avery's brigades to attack the Union XI Corps positions on East Cemetery Hill.

Once started, fighting was fierce: Colonel Andrew L. Harris of the Union 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, XI Corps came under a withering attack, losing half his men.

[78] However, before Longstreet was ready, Union XII Corps troops started a dawn artillery bombardment against the Confederates on Culp's Hill in an effort to regain a portion of their lost works.

The Confederates attacked, and the second fight for Culp's Hill ended around 11 a.m. Harry Pfanz judged that, after some seven hours of bitter combat, "the Union line was intact and held more strongly than before".

In his memoirs, Longstreet states that he told Lee that there were not enough men to assault the strong left center of the Union line by McLaws's and Hood's divisions reinforced by Pickett's brigades.

Opinion was then expressed [by Longstreet] that the fifteen thousand men who could make successful assault over that field had never been arrayed for battle; but he was impatient of listening, and tired of talking, and nothing was left but to proceed.

To save valuable ammunition for the infantry attack that they knew would follow, the Army of the Potomac's artillery, under the command of Brigadier General Henry Jackson Hunt, at first did not return the enemy's fire.

[91] After hearing news of the Union's success against Pickett's charge, Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick launched a cavalry attack against the infantry positions of Longstreet's Corps southwest of Big Round Top.

Many authors have referred to as many as 28,000 Confederate casualties,[fn 9] and Busey and Martin's more recent 2005 work, Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, documents 23,231 (4,708 killed, 12,693 wounded, 5,830 captured or missing).

Additional senior officer casualties included the wounding of Union Generals Dan Sickles (lost a leg), Francis C. Barlow, Daniel Butterfield, and Winfield Scott Hancock.

"[108] But there was only one documented civilian death during the battle: Ginnie Wade (also widely known as Jennie), 20 years old, was hit by a stray bullet that passed through her kitchen in town while she was making bread.

[109] Another notable civilian casualty was John L. Burns, a 69-year-old veteran of the War of 1812 who walked to the front lines on the first day of battle and participated in heavy combat as a volunteer, receiving numerous wounds in the process.

The Army of the Potomac has at last found a general that can handle it, and has stood nobly up to its terrible work in spite of its long disheartening list of hard-fought failures.

"[130] Brigadier General Alexander S. Webb wrote to his father on July 17, stating that such Washington politicians as "Chase, Seward and others", disgusted with Meade, "write to me that Lee really won that Battle!

Although his formal instructions from Confederate President Jefferson Davis had limited his powers to negotiate on prisoner exchanges and other procedural matters, historian James M. McPherson speculates that he had informal goals of presenting peace overtures.

"[132] Compounding the effects of the defeat was the end of the Siege of Vicksburg, which surrendered to Grant's Federal armies in the West on July 4, the day after the Gettysburg battle, costing the Confederacy an additional 30,000 men, along with all their arms and stores.

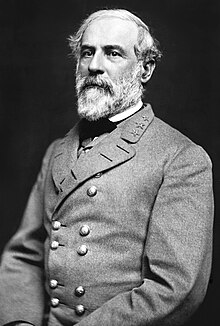

[146] Prior to Gettysburg, Robert E. Lee had established a reputation as an almost invincible general, achieving stunning victories against superior numbers—although usually at the cost of high casualties to his army—during the Seven Days, the Northern Virginia Campaign (including the Second Battle of Bull Run), Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville.

[167] In 2015, the Trust made one of its most important and expensive acquisitions, paying $6 million for a four-acre (1.6 ha) parcel that included the stone house that Confederate General Robert E. Lee used as his headquarters during the battle.

During the Civil War Centennial , the U.S. Post Office issued five postage stamps commemorating the 100th anniversaries of famous battles. See also: Civil War on postage stamps