Ancient Greek art

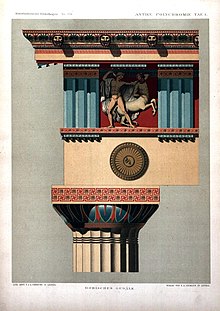

It used a vocabulary of ornament that was shared with pottery, metalwork and other media, and had an enormous influence on Eurasian art, especially after Buddhism carried it beyond the expanded Greek world created by Alexander the Great.

[3] By convention, finely painted vessels of all shapes are called "vases", and there are over 100,000 significantly complete surviving pieces,[5] giving (with the inscriptions that many carry) unparalleled insights into many aspects of Greek life.

[15] The Geometric phase was followed by an Orientalizing period in the late 8th century, when a few animals, many either mythical or not native to Greece (like the sphinx and lion respectively) were adapted from the Near East, accompanied by decorative motifs, such as the lotus and palmette.

[18] By about 320 BC fine figurative vase-painting had ceased in Athens and other Greek centres, with the polychromatic Kerch style a final flourish; it was probably replaced by metalwork for most of its functions.

[20] Fine metalwork was an important art in ancient Greece, but later production is very poorly represented by survivals, most of which come from the edges of the Greek world or beyond, from as far as France or Russia.

[24] Armour and "shield-bands" are two of the contexts for strips of Archaic low relief scenes, which were also attached to various objects in wood; the band on the Vix Krater is a large example.

[41] Unlike authors, those who practiced the visual arts, including sculpture, initially had a low social status in ancient Greece, though increasingly leading sculptors might become famous and rather wealthy, and often signed their work (often on the plinth, which typically became separated from the statue itself).

[48][49] It is generally agreed that "Egyptian statuary of the 2nd millennium BC gave the decisive impulse for the innovation of Greek sculpture in life-size and in hyper formats in the Archaic Period during the late 7th century.

"[48] Free-standing figures share the solidity and frontal stance characteristic of Eastern models, but their forms are more dynamic than those of Egyptian sculpture, as for example the Lady of Auxerre and Torso of Hera (Early Archaic period, c. 660–580 BC, both in the Louvre, Paris).

[52] Archaic reliefs have survived from many tombs, and from larger buildings at Foce del Sele (now in the National Archaeological Museum of Paestum) in Italy, with two groups of metope panels, from about 550 and 510, and the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, with friezes and a small pediment.

Praxiteles made the female nude respectable for the first time in the Late Classical period (mid-4th century): his Aphrodite of Knidos, which survives in copies, was said by Pliny to be the greatest statue in the world.

Realistic portraits of men and women of all ages were produced, and sculptors no longer felt obliged to depict people as ideals of beauty or physical perfection.

[64] The world of Dionysus, a pastoral idyll populated by satyrs, maenads, nymphs and sileni, had been often depicted in earlier vase painting and figurines, but rarely in full-size sculpture.

Now such works were made, surviving in copies including the Barberini Faun, the Belvedere Torso, and the Resting Satyr; the Furietti Centaurs and Sleeping Hermaphroditus reflect related themes.

[65] At the same time, the new Hellenistic cities springing up all over Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia required statues depicting the gods and heroes of Greece for their temples and public places.

[74] Archaic heroon tombs, for local heroes, might receive large numbers of crudely-shaped figurines, with rudimentary figuration, generally representing characters with raised arms.

At the same time, cities like Alexandria, Smyrna or Tarsus produced an abundance of grotesque figurines, representing individuals with deformed members, eyes bulging and contorting themselves.

Figurines made of metal, primarily bronze, are an extremely common find at early Greek sanctuaries like Olympia, where thousands of such objects, mostly depicting animals, have been found.

Other building types, often not roofed, were the central agora, often with one or more colonnaded stoa around it, theatres, the gymnasium and palaestra or wrestling-school, the ekklesiasterion or bouleuterion for assemblies, and the propylaea or monumental gateways.

[97] Greek cities in Italy such as Syracuse began to put the heads of real people on coins in the 4th century BC, as did the Hellenistic successors of Alexander the Great in Egypt, Syria and elsewhere.

[94] The most artistically ambitious coins, designed by goldsmiths or gem-engravers, were often from the edges of the Greek world, from new colonies in the early period and new kingdoms later, as a form of marketing their "brands" in modern terms.

The ekphrasis was a literary form consisting of a description of a work of art, and we have a considerable body of literature on Greek painting and painters, with further additions in Latin, though none of the treatises by artists that are mentioned have survived.

[101] We have hardly any of the most prestigious sort of paintings, on wood panel or in fresco, that this literature was concerned with, and very few of the copies that undoubtedly existed, equivalent to those which give us most of our knowledge of Greek sculpture.

The tradition of wall painting in Greece goes back at least to the Minoan and Mycenaean Bronze Age, with the lavish fresco decoration of sites like Knossos, Tiryns and Mycenae.

[128] The technique has an ancient tradition in the Near East, and cylinder seals, whose design only appears when rolled over damp clay, from which the flat ring type developed, spread to the Minoan world, including parts of Greece and Cyprus.

[129] Round or oval Greek gems (along with similar objects in bone and ivory) are found from the 8th and 7th centuries BC, usually with animals in energetic geometric poses, often with a border marked by dots or a rim.

Islamic art, where ornament largely replaces figuration, developed the Byzantine plant scroll into the full, endless arabesque, and especially from the Mongol conquests of the 14th century received new influences from China, including the descendants of the Greek vocabulary.

[146] In the East, Alexander the Great's conquests initiated several centuries of exchange between Greek, Central Asian and Indian cultures, which was greatly aided by the spread of Buddhism, which early on picked up many Greek traits and motifs in Greco-Buddhist art, which were then transmitted as part of a cultural package to East Asia, even as far as Japan, among artists who were no doubt completely unaware of the origin of the motifs and styles they used.

The study of vases developed an enormous literature in the late 19th and 20th centuries, much based on the identification of the hands of individual artists, with Sir John Beazley the leading figure.

This assumption has been increasingly challenged in recent decades, and some scholars now see it as a secondary medium, largely representing cheap copies of now lost metalwork, and much of it made, not for ordinary use, but to deposit in burials.