Geology

Geology (from Ancient Greek γῆ (gê) 'earth' and λoγία (-logía) 'study of, discourse')[1][2] is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time.

Geologists use a wide variety of methods to understand the Earth's structure and evolution, including fieldwork, rock description, geophysical techniques, chemical analysis, physical experiments, and numerical modelling.

In practical terms, geology is important for mineral and hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation, evaluating water resources, understanding natural hazards, remediating environmental problems, and providing insights into past climate change.

Minerals are naturally occurring elements and compounds with a definite homogeneous chemical composition and an ordered atomic arrangement.

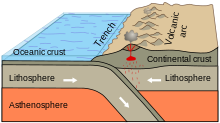

This theory is supported by several types of observations, including seafloor spreading[9][10] and the global distribution of mountain terrain and seismicity.

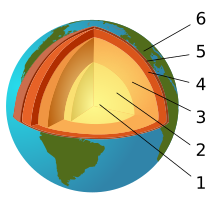

Advances in seismology, computer modeling, and mineralogy and crystallography at high temperatures and pressures give insights into the internal composition and structure of the Earth.

Mineralogists have been able to use the pressure and temperature data from the seismic and modeling studies alongside knowledge of the elemental composition of the Earth to reproduce these conditions in experimental settings and measure changes within the crystal structure.

These studies explain the chemical changes associated with the major seismic discontinuities in the mantle and show the crystallographic structures expected in the inner core of the Earth.

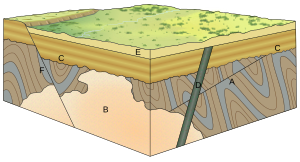

[19] The principle of superposition states that a sedimentary rock layer in a tectonically undisturbed sequence is younger than the one beneath it and older than the one above it.

The geology of an area changes through time as rock units are deposited and inserted, and deformational processes alter their shapes and locations.

In fact, at one location within the Maria Fold and Thrust Belt, the entire sedimentary sequence of the Grand Canyon appears over a length of less than a meter.

Faulting and other deformational processes result in the creation of topographic gradients, causing material on the rock unit that is increasing in elevation to be eroded by hillslopes and channels.

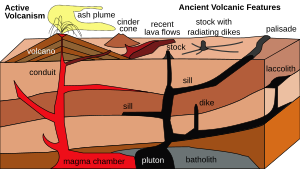

Dikes, long, planar igneous intrusions, enter along cracks, and therefore often form in large numbers in areas that are being actively deformed.

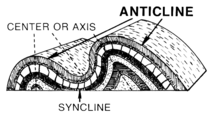

They also plot and combine measurements of geological structures to better understand the orientations of faults and folds to reconstruct the history of rock deformation in the area.

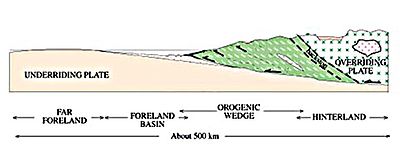

Among the most well-known experiments in structural geology are those involving orogenic wedges, which are zones in which mountains are built along convergent tectonic plate boundaries.

[40] In the analog versions of these experiments, horizontal layers of sand are pulled along a lower surface into a back stop, which results in realistic-looking patterns of faulting and the growth of a critically tapered (all angles remain the same) orogenic wedge.

[45] Geophysical data and well logs can be combined to produce a better view of the subsurface, and stratigraphers often use computer programs to do this in three dimensions.

[46] Stratigraphers can then use these data to reconstruct ancient processes occurring on the surface of the Earth,[47] interpret past environments, and locate areas for water, coal, and hydrocarbon extraction.

Geochronologists precisely date rocks within the stratigraphic section to provide better absolute bounds on the timing and rates of deposition.

[44] With the advent of space exploration in the twentieth century, geologists have begun to look at other planetary bodies in the same ways that have been developed to study the Earth.

This is a major aspect of planetary science, and largely focuses on the terrestrial planets, icy moons, asteroids, comets, and meteorites.

Although planetary geologists are interested in studying all aspects of other planets, a significant focus is to search for evidence of past or present life on other worlds.

One of these is the Phoenix lander, which analyzed Martian polar soil for water, chemical, and mineralogical constituents related to biological processes.

Some resources of economic interests include gemstones, metals such as gold and copper, and many minerals such as asbestos, Magnesite, perlite, mica, phosphates, zeolites, clay, pumice, quartz, and silica, as well as elements such as sulfur, chlorine, and helium.

[57] Geologists and geophysicists study natural hazards in order to enact safe building codes and warning systems that are used to prevent loss of property and life.

During the Roman period, Pliny the Elder wrote in detail of the many minerals and metals, then in practical use – even correctly noting the origin of amber.

[62] Drawing from Greek and Indian scientific literature that were not destroyed by the Muslim conquests, the Persian scholar Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 981–1037) proposed detailed explanations for the formation of mountains, the origin of earthquakes, and other topics central to modern geology, which provided an essential foundation for the later development of the science.

The word geology was first used by Ulisse Aldrovandi in 1603,[67][68] then by Jean-André Deluc in 1778[69] and introduced as a fixed term by Horace-Bénédict de Saussure in 1779.

[73][74] William Smith (1769–1839) drew some of the first geological maps and began the process of ordering rock strata (layers) by examining the fossils contained in them.

In his paper, he explained his theory that the Earth must be much older than had previously been supposed to allow enough time for mountains to be eroded and for sediments to form new rocks at the bottom of the sea, which in turn were raised up to become dry land.

A. Strike-slip faults occur when rock units slide past one another.

B. Normal faults occur when rocks are undergoing horizontal extension.

C. Reverse (or thrust) faults occur when rocks are undergoing horizontal shortening.